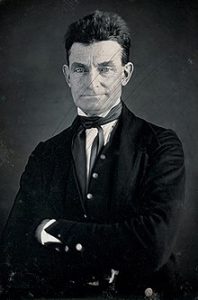

Sydney Howard Gay, courtesy of Columbia University Libraries

The Record of Fugitives, a journal kept by abolitionist newspaperman Sydney Howard Gay, was a secret record detailing the escapes of over 200 enslaved people who passed through New York City during their flight to freedom. [1] This remarkable primary source and the fascinating stories it contains remained largely unknown and unexamined by historians until Eric Foner finally analyzed the document in detail for Gateway to Freedom (2015), his recent capstone study of the Underground Railroad. Gay’s journal reveals a number of insights, including important ones about the frequency of group escapes. Foner writes that “while the popular image of the Underground Railroad tends to focus more on lone fugitives making their way North on foot, in fact more slaves who passed through New York in the mid-1850s escaped in groups than on their own.” [2]

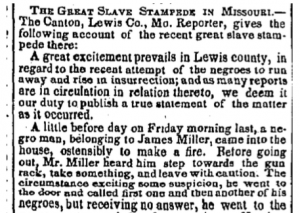

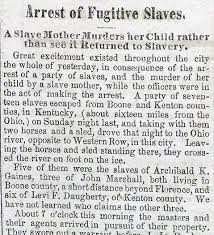

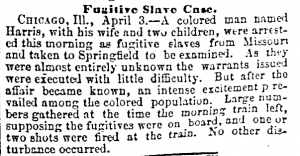

Eric Foner, the Dewitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University and author of Pulitzer Prize-winning The Fiery Trial, focuses on the Underground Railroad in New York City in the 1840s and 1850s but his work has national implications. In particular, the Record of Fugitives includes valuable information about slave stampedes that traveled through New York. In Gateway to Freedom (2015), Foner uses the word “stampede” twice in reference to group escapes. In 1857, he writes, “a newspaper reported a ‘general stampede,’ (as the press called group escapes) from Dover, the state capital, ‘by the underground railroad.’” [3] Here, Foner is explicitly describing the term “stampede” as used by the antebellum press. He also employs the term later on his own when describing a number of stampedes out of Chestertown, Maryland, which was “particularly vulnerable to mass escapes.” [4] Within only two months in 1855, at least three groups of seven or more individuals are reported by the local newspaper to have successfully escaped from Chestertown. Foner writes that “Not surprisingly, these ‘stampedes’ alarmed Chestertown slaveowners,” asserting a direct connection between mass escapes and slaveholders’ anxiety over the fugitive slave crisis, an anxiety heavily reinforced by the press. [5]

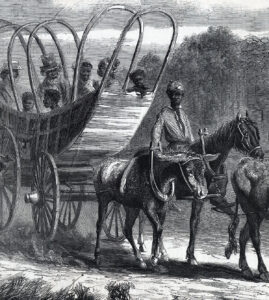

Throughout the book, there are at least twelve cases of group escape depicted for the 1840s and 1850s. For example, Foner writes of the well-known 1848 attempted escape of 76 individuals on the schooner Pearl. This escape from Washington, DC was “particularly alarming to slaveholders” in the enormous number of escapees and the level of planning required to execute the escape. [7] Other examples of stampedes, such as the 35 enslaved people who fled from a single county in Maryland on a single day in 1850, are used to emphasize the anxiety that slaveholders felt about stampedes. [8]

However, Foner does spend some time analyzing certain group escapes themselves, and makes some valuable claims for this project. For example, he writes that ”when slaves escaped in groups, these frequently included relatives—husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, even, as in the case of eleven women or married couples and one man in Gay’s records, small children.” [9] Additionally, Foner’s analysis of how group escapes occurred reveals the instrumental role that the Underground Railroad and its agents played in stampedes. Every group escape documented by Foner involved at least one antislavery agent who housed, fed, or directed the group to safety.

Harriet Tubman, courtesy of the National Women’s History Museum

Harriet Tubman directed one of the most dramatic examples of such group escapes pulled from the Record of Fugitives. In 1856, Tubman and four escapees fled from the Eastern Shore of Maryland by foot. After being forced to hide from the slaveholders in a “potato hole” for a week, Tubman tapped into the Underground Railroad network to help get the four enslaved men to safety in Wilmington, Delaware. Then, with the help of vigilance committee operative William Still, the group took a train from Philadelphia to New York, where they were placed under the protection of Gay. From there the slaves were sent to Syracuse and then Canada. [10] Without the Underground Railroad and its many known and unknown agents willing to take the enormous risk of traveling with large groups of fugitives, slave stampedes would never have been possible.

————————————————————————————————

[1] Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom, The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), 10.

[2] Foner, 122.

[3] Foner, 229-230.

[4] Foner, 156.

[5] Foner, 206.

[6] Foner, 206.

[7] Foner, 205.

[8] Foner, 116.

[9] Foner, 200.

[10] Foner, 191-192.

On Friday evening, January 9, 1863, Abraham Lincoln held a private meeting at the White House with two key Republican senators –

On Friday evening, January 9, 1863, Abraham Lincoln held a private meeting at the White House with two key Republican senators –