Marion County Map, Historical Atlas 1855.

In November of 1853, 11 enslaved people escaped from six different farms in Marion County, located right along the Mississippi River. The group of freedom seekers converged from their different escape points, joining together on a Saturday evening to cross the Mississippi River heading eastward. [1] The group traveled through the night, moving through Missouri and eventually arriving in Quincy, Illinois. By Sunday morning, the group had reached nearby Menden. Then they pursued freedom in Chicago. [2]

The Marion County group escape was just one of many mass slave escapes profiled in James Patrick Morgans’ book, The Underground Railroad on the Western Frontier (2010). Morgans focuses on slave escapes from the western border of Missouri and does not explicitly use the term stampede within the text, but his book covers a number of important group escapes, including some within our main project area (such as the one from Marion).[3]

Morgans also describes how increasing slave escapes along Mississippi River prompted many slaveholders in Eastern Missouri to move their slaves into the interior of the state, closer to the Missouri River and toward the states’ western border. During the 1850s, Missouri slaveholders hoped that Kansas Territory would eventually become a slave state, permanently fortifying the western border from slave escape.

Burlington Hawk-Eye, July 11, 1850. Courtesy of Newspapers.com

Yet Missouri slaveholders were rightfully concerned. Throughout the 1850s, the eastern border of Missouri became riddled with slave escapes like the 1853 Marion County group escape described above. Enslaved people residing along the Mississippi River in Missouri used their geographical location to their advantage, slipping across the Mississippi and moving north and east towards the free states of Iowa and Illinois. Many slaveholders along the eastern border became repeated victims of such slave escapes. In Clark County, MO, a slaveholder by the name of Ruel Daggs experienced the difficulties of owning slaves in the most eastern parts of Missouri. [4] In 1848, one of Daggs’ 16 slaves, John Walker, escaped his farm. Walker, who found safety in Salem, Iowa, eventually returned to Clark County in June to help rescue other slaves, helping not only his wife and children but also seven others escape from Dagg’s farm. [5] With help from a free black man in the county, Walker and his group built a raft and crossed the Mississippi River into Iowa. [6] Daggs responded to this episode by organizing a large armed posse of Missouri slave catchers, who eventually crossed over into Iowa and threatened the heavily Quaker settlement with violence. Some of the freedom seekers were recaptured, but most escaped. The case also led to a major verdict in Daggs’s favor (under the 1793 fugitive statute) in the summer of 1850 (before passage of the new federal law), but Daggs was never able to recover the thousands of dollars that the courts had ordered him to be paid.

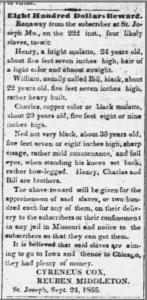

St. Joseph Commercial Cycle, October 5, 1855. Courtesy of Newspapers.com

Although some slaveholders believed that moving their human property to the western part of Missouri would prevent mass escapes like the one experienced by Ruel Daggs, they were soon put on notice that such group flight could occur out west as well when 30 more slaves on the Kansas border attempted to escape bondage in 1850. [7] The group, “armed with knives, clubs and three guns,” were eventually stopped, but there were more efforts to come. [8] In 1855 in the western town of St. Joseph, MO, a slaveholder offered a $200 dollar reward for each of his four escaped slaves, double the amount of a typical reward for recapture. [9] According to Morgans, by the mid-1850s, it “wasn’t unusual to see ten or a dozen successfully escape at the same time- especially from western Missouri.” [10]

While group escapes may have proved more feasible along the eastern counties of Missouri, Morgans’ research on the western frontier demonstrates that mass escapes could and did occur almost anywhere.

[1] James Patrick Morgans, The Underground Railroad on the Western Frontier (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. 2010), 69.

[2] Morgans, 69.

[3] Morgans, 1.

[4] Morgans, 94.

[5] Morgans, 94.

[6] Morgans, 95.

[7] Morgans, 77.

[8] Morgans, 77.

[9] Morgans, 77.

[10]Morgans, 77.