Howard, Victor B. “The Civil War in Kentucky: The Slave Claims His Freedom.” The Journal of Negro History 67, no. 3 (1982): 245–56. [JSTOR]

Lobell, Jarrett A. “A Path to Freedom.” Archaeology 73, no. 3 (2020): 38–43. [JSTOR]

Lucas, Scott J. “High Expectations: African Americans in Civil War Kentucky.” Negro History Bulletin 64, no. 1/4 (2001): 19–22. [JSTOR]

McBride, W. Stephen. “Camp Nelson and Kentucky’s Civil War Memory.” Historical Archaeology 47, no. 3 (2013): 69–80. [JSTOR]

Myers, Marshall, and Chris Propes. “‘I Don’t Fear Nothing in the Shape of Man’: The Civil War and Texas Border Letters of Edward Francis, United States Colored Troops.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 101, no. 4 (2003): 457–78. [JSTOR]

Rhyne, J. Michael. “‘A Blood Stained Sin’: Slavery, Freedom, and Guerilla Warfare in the Bluegrass Region of Kentucky, 1863-65.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 112, no. 4 (2014): 553–87. [JSTOR]

Sears, Richard. “John G. Fee, Camp Nelson, and Kentucky Blacks, 1864-1865.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 85, no. 1 (1987): 29–45. [JSTOR]

Howard, Victor B. “The Civil War in Kentucky: The Slave Claims His Freedom.” The Journal of Negro History 67, no. 3 (1982): 245–56. [JSTOR]

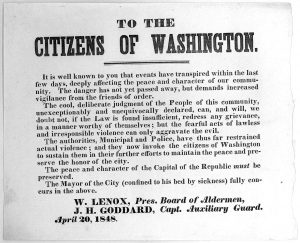

Victor B. Howard explains how enslaved individuals in Kentucky were not only essential participants in the Civil War, but also actively used it to frustrate and ultimately destroy the institution of slavery. In the beginning stages of the war, enslaved men managed to stay informed about its progress despite information suppression. Enslaved men were also used as servants in the US army. As the war progressed, enslaved individuals began refusing to work without pay and escaping more frequently, especially after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The War Department started to enlist enslaved individuals in early 1863, and when Kentucky refused this at first, enslaved men escaped to other states to serve in the army. This ultimately led to the reversal of Kentucky’s policy and allowed enslaved men to enlist and be emancipated. The question then became about what would happen with their families in terms of their treatment and emancipation. Camp Nelson was featured in this article because it was central to this question, given what has been described as the tragedy when 400 wives and children of USCT soldiers were forced by staff to leave the site. The anger and resistance of Black soldiers whose families were driven out led to the reversal of this policy at Camp Nelson, and contributed to the later emancipation of soldiers’ families. This law remained contested after the war ended and so did the movement of Black individuals to cities and towns from rural areas in Kentucky. Commander John Palmer created a pass system to counter the opposition to Black mobility which symbolized a move towards the full achievement of freedom and destruction of slavery six months before the Thirteenth Amendment passed.

Howard uses a combination of letters, newspapers and congressional reports as well as books and journal articles.

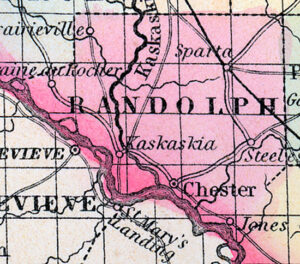

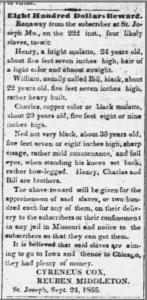

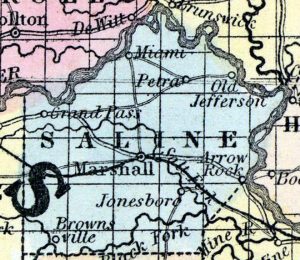

Howard does not explicitly use the term “stampede” in the body of his article, although he does use it once in the end notes when mentioning the Madison (Indiana) Courier reporting a stampede from Ghent, Kentucky. At the beginning of his article, he discusses various group escapes or escape plots from Fayette, Owen, and Gallatin Counties that were reported on by newspapers. Later, he references escapes from Henry County, and that in November 1861 eight enslaved individuals had reportedly run away to an army Camp near Nolin from Green River County, in the same month a group of freedom seekers escaped to camp Haycroft from southern Kentucky, and in January 1862, freedom seekers who had been captured by Confederates in Bowling Green escaped to a camp in Mumfordsville.

Lobell, Jarrett A. “A Path to Freedom.” Archaeology 73, no. 3 (2020): 38–43. [JSTOR]

Using the various findings of Stephen McBride and a team of researchers from Transylvania University, Jarrett A. Lobell discusses Camp Nelson’s role in the Civil War as it became the largest USCT recruitment center in Kentucky and one of the largest in the country. Before the archaeological research, what was previously known to be remaining at the site was the Oliver Perry house, also known as the “White House,” and a number of “stone and earthen” remains. According to Lobell, however, the newer discoveries by McBride and researchers, help piece together the lives of soldiers and their families who resided at Camp Nelson during and after the war. Certain findings shed light on the living conditions of the USCT soldiers in terms of the barracks and diets, as well as the weapons they used. Although not much physical evidence remained at the site where women and children lived, Lobell states that McBride used a combination of research methods to produce a realistic portrayal of “the Home for Colored Refugees.” He did find evidence of food preparation, heating, and other occupations women took up to make money such as doing laundry. Lobell notes that one of the particularly special findings was a photography studio because it was the first of its kind to be discovered at a site associated with the Civil War (and because photography was also typically done in tents, not buildings). The studio’s existence at Camp Nelson during the war somehow evaded documentation but was discovered when the team found certain materials, such as stencils, a glass plate, and a frame with the name C.J. Young, who was the photographer.

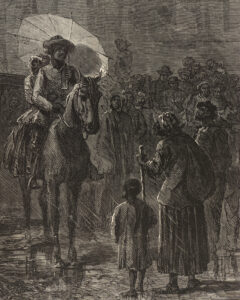

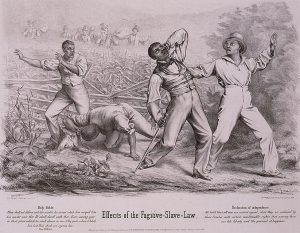

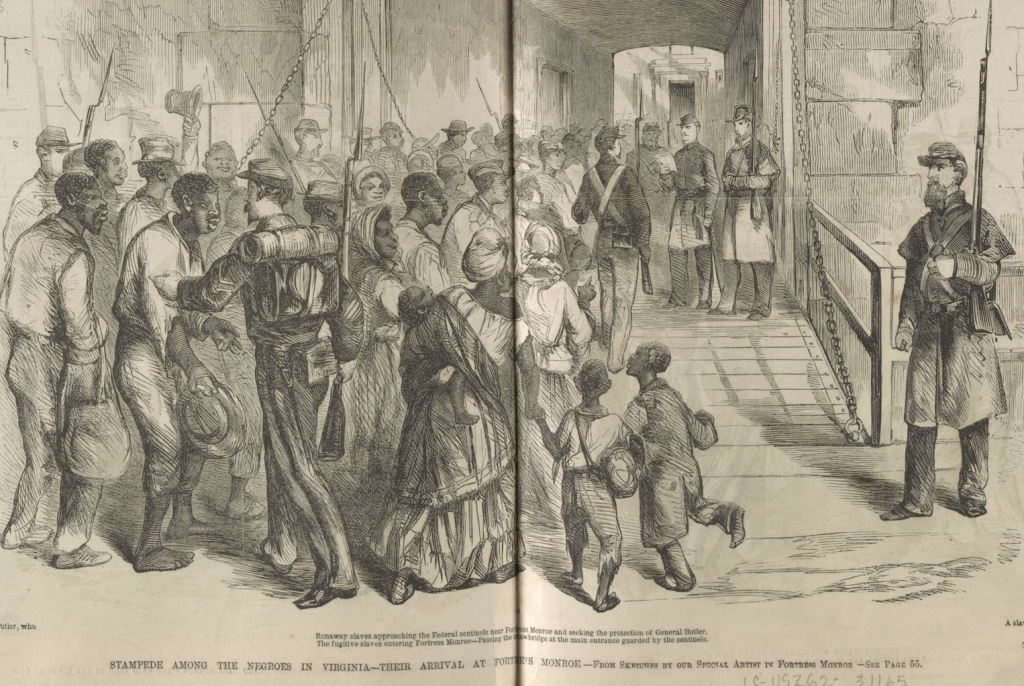

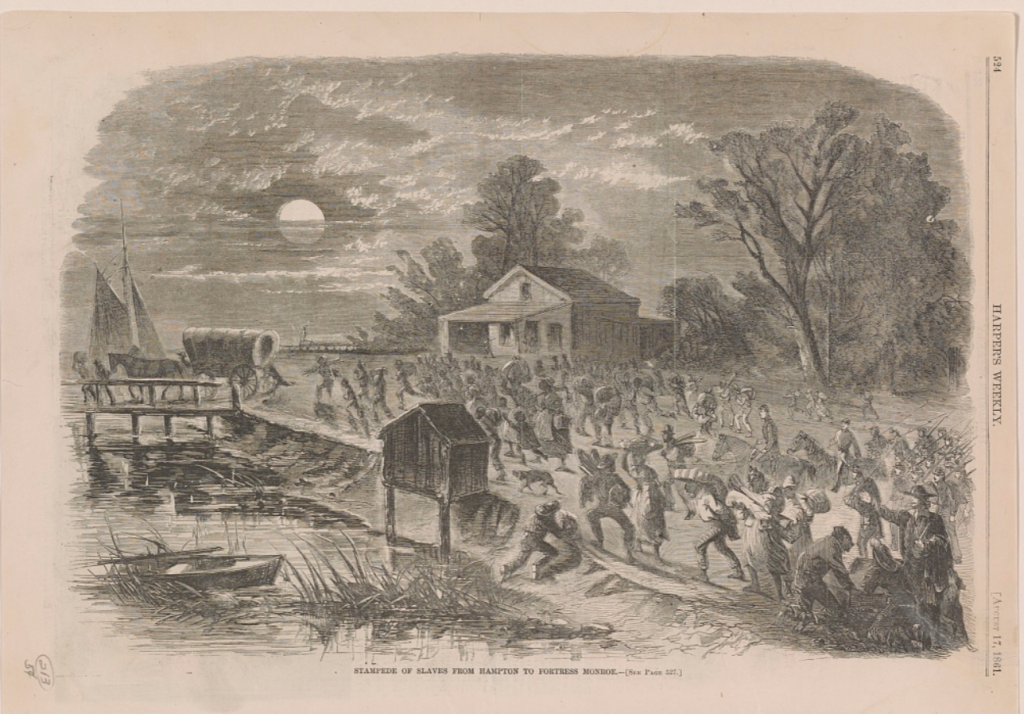

Lobell includes images of archaeological discoveries at Camp Nelson such as glass bottles for hair products, pottery, utensils, remnants of a doll, the materials which led to the discovery of the photography studio as well as maps and photos of living spaces. Lobell also uses a photograph of Private William Wright, a soldier in the 114th regiment of the USCT who enlisted at Camp Nelson and an image of a family’s escape from slavery after the Emancipation Proclamation was passed.

Lobell does not use the term “stampede,” but he does discuss how enslaved men began escaping slavery to join the army as the US army moved into Confederate territory. He also explains how the families of USCT soldiers escaped slavery to join them at Camp Nelson, no matter the poor conditions or if they were driven out by staff, which happened numerous times.

Lucas, Scott J. “High Expectations: African Americans in Civil War Kentucky.” Negro History Bulletin 64, no. 1/4 (2001): 19–22. [JSTOR]

Scott J. Lucas discusses the hostile environment for enslaved and free Black individuals in Kentucky for the duration of the Civil War in terms of harassment, the imposition of vagrancy laws and interference in Black churches and schools. Policies in Kentucky regarding enslaved men began to change around 1862 and by mid 1864, the US army began actively recruiting any and all Black men in Kentucky. Several military centers were established across the state, and the wives and children of the soldiers either escaped slavery to join the men or they were kicked out of their homes because slaveholders perceived them to be less valuable in terms of the labor they could provide. Out of all of the centers, Lucas emphasized that Camp Nelson saw the most freedom seekers. Upon arrival however, wives and children were often met with poor conditions. There was overcrowding, a shortage of resources and employment, and uncertainty as the inconsistent policy regarding refugees notably pushed by Brigadier General Fry made clear that they could be returned to their former condition at any moment. Even after Congress passed legislation declaring that families of Black soldiers be emancipated, they still faced resistance from white Kentuckians who sought to limit their mobility.

Lucas uses a combination of books, newspaper articles, a personal letter, and diaries.

Lucas does not explicitly use the term “stampede,” but he describes various escapes from slavery to military centers to Camp Nelson. One story he describes was about an enslaved man named Henry, who was married to a woman named Lucinda who was enslaved to Reverend William Pratt. Henry escaped from Lexington to Camp Nelson to be emancipated and after two weeks of deliberation, Lucinda escaped Pratt to join him. Scott also explains the story of Alfred, who was the father of an enslaved individual who escaped to Camp Nelson and after visiting him on various occasions, he eventually joined his son and the Union army.

McBride, W. Stephen. “Camp Nelson and Kentucky’s Civil War Memory.” Historical Archaeology 47, no. 3 (2013): 69–80. [JSTOR]

Stephen W. McBride explains that Camp Nelson and its past as a prominent African American military center and refugee camp had long been erased from history to bolster the “Lost Cause” narrative that Kentucky endorsed after the Civil War. However, he argues that the recent designation of Camp Nelson as the “Camp Nelson Civil War and Heritage Park” and the production of documents, oral histories and archaeological findings, undermines this narrative and has the potential to alter public memory. Specifically, the story of Camp Nelson reaffirms Kentucky’s contributions to the Union war effort, highlights the conflict’s roots in slavery, and exemplifies how African Americans drove their own futures in terms of emancipation and civil rights during and after the war.

McBride describes how recent findings at Camp Nelson, particularly archaeological discoveries at the USCT barracks, refugee encampment, and the “Home for Colored Refugees,” shed light on the experiences of African American soldiers and their families in the fight for emancipation and civil rights during and after the war. He details various findings in terms of living and eating arrangements of soldiers and their families as well as the occupations and entrepreneurial tendencies of women before they were forced to evacuate the site and after they were allowed back. McBride, in addition to archaeological evidence, draws on contemporary evidence from antislavery and contraband aid societies, who were providing aid at Camp Nelson. He also uses a combination of historic photographs of USCTs and modern-day photographs of the site. Courtesy of the National Archives Records Administration, the first photograph is a map of Camp Nelson and the other is of USCT soldiers training in front of the barracks. McBride then includes his own photographs of a chimney at the barracks and a rubber button. He also uses a photograph from the University of Kentucky Special Collections of refugee cottages with many people congregated outside.

McBride does not use the term “stampede” but does mention how the recent research at Camp Nelson begins to tell a fuller story of the role the site played in the escapes of enslaved individuals and how those individuals went on to aid the Union war effort. He describes the 1864 Camp Nelson, Kentucky stampede when 400 enslaved individuals escaped and made their way to the site to be emancipated, and that this was the turning point in Kentucky’s policy for enlisting.

Myers, Marshall, and Chris Propes. “‘I Don’t Fear Nothing in the Shape of Man’: The Civil War and Texas Border Letters of Edward Francis, United States Colored Troops.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 101, no. 4 (2003): 457–78. [JSTOR]

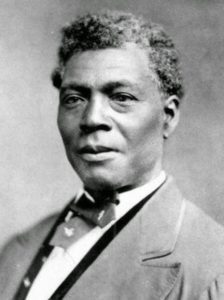

Using the letters of Edward Francis, Marshall Myers and Chris Propes highlight the resolve of Black soldiers in the army despite the poor conditions they faced during their service. Myers and Propes explain that Francis enlisted in June 1864 either by recruitment or through his own escape from slavery. He had previously been enslaved by Edy Francis who lived with her son, Joseph L. Francis in Madison County. In 1864, when Edward Francis enlisted in London, Kentucky, he was soon taken to Camp Nelson to serve in the 114th regiment of the US Colored Troops. This regiment observed Robert E. Lee’s surrender in Appomattox before being moved to the Texas border for two more years. Myers and Propes state that after Francis returned to his home in 1867, he reunited with his wife, Liza Francis, and had two more children. After she passed away in 1880, Edward Francis remarried Susan Miller in Madison County which was his essentially the last record of his life.

Myers and Propes include letters that Edward Francis wrote to Liza Francis from June 20, 1864 to October 12, 1866 and one letter written by Liza Francis. These were found in the collection of the man who enslaved Liza Francis, although it was not made clear who this man was. Myers and Propes identified apparent themes in these letters, specifically of Edward Francis’s anxiety about the wellbeing of him and his family, homesickness, the importance of education, and his prioritization of religion while only including discussion of freedom and the war once. Myers and Propes include various images of Camp Nelson’s Soldiers’ Home, refugee quarters, refugee school, a map, and the first page of one of Edward Francis’s 1865 letters. These images were from the National Archives, the Kentucky Library and Museum, Western Kentucky University, Eastern Kentucky University Archives, Photographic Views of Camp Nelson and Vicinity, and the Kentucky Historical Society Special Collections.

There is no mention of the term “stampede” but Myers and Propes do acknowledge that there was a “contingent” of enslaved individuals in Madison County who escaped to enlist in the army, and that it was possible Edward Francis was a part of it.

Rhyne, J. Michael. “‘A Blood Stained Sin’: Slavery, Freedom, and Guerilla Warfare in the Bluegrass Region of Kentucky, 1863-65.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 112, no. 4 (2014): 553–87. [JSTOR]

Michael J. Rhyne argues that Kentucky politics during the Civil War exemplify how conflict in the US during this time can be better identified as a battle against federal power than the conventional characterization as a battle between North and South. Specifically, Rhyne charts how early in the war, pro-slavery Kentuckians who believed their interests were better served by the Union, supported the war effort from afar or served in the army themselves. However, as Kentucky shifted its stance toward the war and particularly toward Black recruitment, those pro-slavery Kentuckians began to clash with the Lincoln administration’s policies around slavery in their state. Their response was to revolt and wage guerilla war to spite the federal government and disrupt its war effort. What resulted was Black soldiers and white citizens alike being targeted and subjected to their intimidation and violence.

Camp Nelson was featured in this article because according to Rhyne, over time it became the most significant military training and recruitment center in Kentucky. For this reason, it was also subject to substantial scrutiny by slaveholders. Rhyne essentially characterizes the site as the vivisection of the nation’s debate about freedom that captured slaveholders’ anxiety concerning increasing escapes from slavery.

Rhyne uses a variety of sources such as books, newspaper articles, encyclopedia entries, the Kentucky Historical Marker Database, an affidavit, letters from the Office of the Secretary of War found in the National Archives, personal correspondence and telegrams, as well as historical reports and military documents.

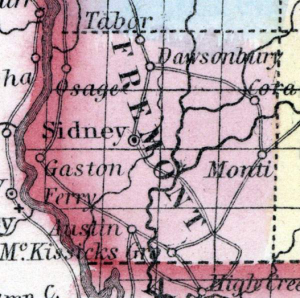

Rhyne does not use the term “slave stampede,” but he does mention several individual and group escapes from slavery. First, he describes the Camp Nelson stampede in May of 1864, in which 250 freedom seekers made their way from Danville to Camp Nelson, but were turned away and instead taken in by the Sanitary Commission. Rhyne provides several other similar instances where freedom seekers arrived at army camps like Camp Nelson but were not received because they did not have the documentation granting permission to enlist. He describes a report from the provost marshal in Lebanon, Marion County who said 17 Black men were denied from the army recruiting office for this reason. Even though they were given “passes” to ensure they returned safely to the plantations, they were kidnapped and attacked by citizens. Rhyne notes that similar situations occurred in Nelson and Spencer counties. Lastly, another report from the provost marshal explains how the “Thirteenth Kentucky Cavalry” denied enlistment to Black men seeking the opportunity.

Notably, Rhyne acknowledges how families of soldiers frequently escaped to army camps to be together. He details the specific escape story of Patsey Leach, whose husband Julius enlisted as a USCT soldier in the fall of 1864. Leach’s slaveholder, however, upset about Julius’s enlistment (even though he was not his direct slaveholder), projected his anger onto Patsey. Julius was killed in battle, but suffering ruthless brutality at the hands of her slaveholder, Patsey along with her youngest child escaped and sought refuge in Lexington. After what is referred to as the “Camp Nelson tragedy” in 1865 when Brigadier General Fry expelled hundreds of women and children from the site in the heart of winter, Congress passed legislation emancipating families of USCT soldiers. Using this new policy, Leach petitioned federal officials to free her other four children, although Rhyne does not provide what the outcome was.

Sears, Richard. “John G. Fee, Camp Nelson, and Kentucky Blacks, 1864-1865.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 85, no. 1 (1987): 29–45. [JSTOR]

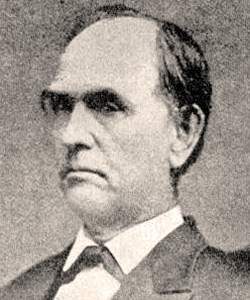

Richard Sears describes the story of Reverend John Gregg Fee, a missionary who had been supported earlier by the American Missionary Association, and his experience at Camp Nelson as educator, preacher, and advocate for freedom and equality. Sears explains how Fee became involved in Camp Nelson when enslaved individuals began enlisting there in large numbers. He spearheaded the creation of a school, provided clothing for women and children, and later on a refugee encampment (he did not receive assistance from the AMA until much later). Fee’s unrelenting attempts to provide a safe and supportive shelter for refugees and the resistance he repeatedly faced, notably by Brigadier General Speed Smith Fry, illustrates how Camp Nelson and its inhabitants’ fate was often subject to the individual prejudices of the staff. Even in 1865 after slavery had been dying out in Kentucky, the transition to freedom and the question of equality loomed large, especially at Camp Nelson. Sears notes how white staff sought to assert their dominance by the construction of hierarchy and arbitrary titles. During this period, Black individuals living at Camp Nelson also faced difficult conditions as was evident by the rising death toll, although Fee maintained that this condition was unequivocally better than one of servitude.

Sears uses letters written primarily by Fee, a report issued by Camp Nelson’s Headquarters in July 1864 and various books. He includes photographs of Camp Nelson’s barracks, headquarters, and a class in session, courtesy of the Berea College Archives and the University of Kentucky Photographic Archives.

Sears does not use the term “stampede” nor does he describe any group escapes. However, he highlighted how Camp Nelson remained the site in Kentucky that continued to attract the most refugees, even after some of the staff drove them out various times.