‘Rebels on the Border’ Cover, from Target Bookstore

In the summer of 1848, dozens of enslaved Kentuckians set out on the dangerous path to freedom. According to Aaron Astoer, “The largest plot in the Bluegrass…involved [reportedly] seventy-five slaves who had escaped Fayette and Bourbon countries with the help of a white abolitionist at Danville’s Centre College and numerous free blacks.” 1 The freedom seekers had armed themselves and had been traveling in the direction of the Ohio River before being recaptured in the city of Cynthiana. Astor only uses the term ‘stampede’ in his 2012 book Rebels on the Border: Civil War, Emancipation, and the Reconstruction of Kentucky and Missouri twice, and does not use it to refer to such organized group escapes. The author mentions that locals of Lexington were particularly flabbergasted by this event, as “most of the participating slaves were ‘trusted house servants of Lexington’s most socially prominent families.’”2

In the beginning of Astor’s narrative, he describes some other antebellum examples of enslaved people rebelling against slaveholders. “One large slave ‘conspiracy’ in the western border states occurred not in the Bluegrass but in western Kentucky’s Hopkinsville, where a foiled Christmas insurrection in 1856 spurred panic and ‘excitement’ throughout the entire state,” Astor writes, noting that even rumors of this sort of activity were terrifying to the slaveholders, who were extremely averse to the suggestion that their power over the people they had enslaved could be challenged.3

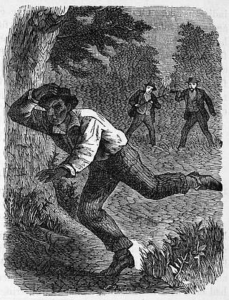

Enslaved Persons’ Rebellion, from ThoughtCo

Even though the journey out of bondage was perilous and sometimes unsuccessful, it was also an obvious reclamation of power by the freedom seekers. Astor acknowledges that “[o]ther than outright insurrection, running away was the slave’s gravest political act of resistance. It directly usurped the master’s authority…”4 White enslavers experienced a growing anxiety over the threat of enslaved people running away or arming themselves en masse, especially as the tensions which led to the Civil War heightened. It got to the point that untrue rumors of rebellion circulated amongst the townspeople routinely: “The appearance of slave conspiracies during seminal events…underscores the latent political power vested in the ‘apolitical’ slave population.” 5 Astor notes that even though many of the feared insurgent plots seemed to have been conjured up entirely in the minds of slaveholders, the enslaved were able to observe their enslavers’ panic and use it against them. Enslaved people’s different forms of rebellion shattered the wishful illusion that this system was morally neutral and could continue without consequences.

During wartime, Astor notes the examples of stampedes behind Union lines, and how the “rush of slaves off the farms of Little Dixie and the Bluegrass stunned white conservatives and Union military officials alike. Sporadic violence against enlistees hardly stemmed the tide of black men –and often black women as well– who stampeded into the army of liberation.”6 Astor refers to black people as ‘stampeding’ into the army twice in his book. Fighting in the Civil War for the right of all enslaved people to be freed was the ultimate revolution in which freedom seekers could have taken part, and the use of the word “stampede” to describe their fervor for enlistment is apt.

[1] Aaron Astor, Rebels on the Border: Civil War, Emancipation, and the Reconstruction of Kentucky and Missouri (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012), 67-68.

[2] Astor, 68.

[3] Astor, 68.

[4] Astor, 69.

[5] Astor, 70.

[6] Astor, 144.