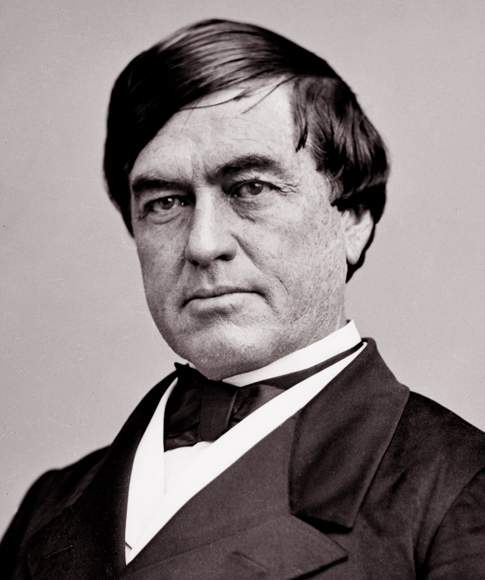

Kentucky politician and slaveholder Cassius Clay (House Divided Project)

In 1847, an enslaved Kentuckian named Jack accompanied his enslaver, Kentucky politician-turned-soldier Cassius M. Clay, to the frontlines of the US-Mexican War. During his time in Mexico laboring as Clay’s personal body servant, Jack may well have heard the term “stampede” tossed around in conversation. As Jack would have learned, the unfamiliar, Spanish-language word was frequently invoked in the southwestern borderlands to describe the uncontrollable movement of cattle and horses.

A year later, after Clay and Jack returned home from Mexico, Jack became involved in a different sort of “stampede”: a “slave stampede” that rocked Lexington, Kentucky, as more than 40 enslaved men, heavily armed, departed Lexington in “military file” and exchanged gunfire with pursuing whites. In the aftermath of the stampede, witnesses and prosecution harped on the connection between Jack’s Mexican War experience and his role as an alleged “ringleader” of the August 1848 stampede. [1] Jack’s story encapsulates how the term “stampede” entered the American vocabulary during the US-Mexican War, and then how Americans on both sides of the slavery issue appropriated the term to describe a revolutionary new form of enslaved resistance that seemed eerily similar to war.

Use of the word “stampede” spiked dramatically during the US-Mexican War from 1846-1848, as indicated by a search of US papers at the Newspapers.com database (Newspapers.com)

The US-Mexican War was largely responsible for popularizing the term “stampede” to American audiences and readers. It was no coincidence that the usage of “stampede” in American newspapers spiked dramatically in 1847, as the war escalated and letters and dispatches from the frontlines conveyed the term back to American readers. For instance, during the spring of 1847, a letter from a US Army surgeon in Mexico describing “how the Indians effect stampedes among their horses” appeared widely in papers across the United States. [2] Just a year later in 1848, John Russell Bartlett included the increasingly popular word in his Dictionary of Americanisms, defining stampede (or “stampado”) as “a general scamper of animals on the Western prairies, generally caused by a fright.” Notably, Bartlett also included an entry that suggests just how influential the US-Mexican War was in popularizing the term with American audiences. Bartlett defined “to stampede” as “to cause to scamper off in a fright,” and provided an example of a US Army colonel whose pursuit of Mexican soldiers was frustrated by “a war party of Indians, who succeeded in stampeding a large band of the army horses.” [3]

It did not take long for newspaper editors and journalists to apply the term “stampede” to the mass escapes launched by enslaved people. As early as April 1847, newspaper editors in Cincinnati ran the first known headline describing a “Grand Stampede” of enslaved people from Kentucky. It is likely no coincidence that the “slave stampede” metaphor was born in the Kentucky-Ohio borderlands, given Kentuckians’ strong support for the war and the frequent frontline reports that made it back into Kentucky newspapers. As Jack’s story indicates, some of the enslaved people who participated in stampedes had been in Mexico with their enslavers and may have heard the term there themselves. Moreover, many of the white Kentuckians who were involved in the pursuit and capture stampede participants like Jack were themselves veterans of the Mexican War. [4]

[1] Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. Henry Slaughter, et. al, John A. McClung’s Trial Notes, September 1848

[2] For just a few of many examples, see “Stampedes,” Washington DC National Intelligencer, April 21, 1847; “Stampedes,” Bangor (ME) Courier, June 1, 1847; Charleston (SC) Daily Courier, April 22, 1847.

[3] John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States (New York: Bartlett and Welford, 1848), 330-1, [WEB].

[4] See the trial transcript of the 1848 Lexington Stampede for numerous references ot participants’ Mexican War connections. Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. Henry Slaughter, et. al, John A. McClung’s Trial Notes, September 1848. One of the white pursuers wounded by freedom seekers, Charles H. Fowler, jr., was a Mexican War veteran.