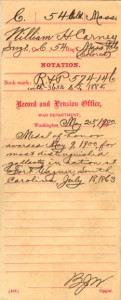

On May 31, 1897, the city of Boston erected a monument created by the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in honor of the 54th Massachusetts and its colonel, Robert Gould Shaw. The monument commemorates the regiment’s participation in the second attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 18, 1863. The August 8 edition of Harper’s Weekly, available in a transcribed form at Assumption College’s primary source-rich database “Northern Vision of Race, Religion & Reform” recorded that at Fort Wagner: “The 54th Massachusetts (negro), whom Copperhead officers would have called cowardly if they had stormed and carried the gates of hell, went boldly into battle, for the second time, commanded by their brave Colonel, but came out of it led by no higher officer than the boy, Lieutenant Higginson.” Sergeant James Henry Gooding of Company C of the 54th wrote weekly letters to the New Bedford Mercury, a periodical in the company’s hometown. Gooding’s letters were published as On the Altar of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front, and some are available on Google Books. Gooding’s July 20 letter documents the 54th’s attack of Fort Wagner: “When the men saw their gallant leader [Colonel Shaw] fall, they made a desperate effort to get him out, but they were either shot down, or reeled in the ditch below. One man succeeded in getting hold of the State color staff.” The “one man” who reached the flag was Sergeant William H. Carney, originally of Norfolk, Virginia, as he maintained the sanctity of the flag by keeping it from touching the ground. Though Carney was wounded in both of his legs, one arm, and his chest he kept the flag aloft and is recorded as exclaiming, “the old flag never touched the ground, boys!” During the 1897 monument dedication Carney raised the flag once more, an action that Booker T. Washington recorded in his autobiography, Up from Slavery (1901), as causing such an effect on the crowd that “for a number of minutes the audience seemed to entirely lose control of itself.” Three years later, Carney received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions at Fort Wagner. Though Carney is often listed as the first African-American recipient of the Medal of Honor, instead, Carney’s rescue of the colors at Fort Wagner was the earliest African-American act of bravery to be recognized with a Medal of Honor. The medal notation reads: “Medal of Honor awarded May 9, 1900, for most dinstinguished gallantry in action at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, July 18, 1863.”

On May 31, 1897, the city of Boston erected a monument created by the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in honor of the 54th Massachusetts and its colonel, Robert Gould Shaw. The monument commemorates the regiment’s participation in the second attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 18, 1863. The August 8 edition of Harper’s Weekly, available in a transcribed form at Assumption College’s primary source-rich database “Northern Vision of Race, Religion & Reform” recorded that at Fort Wagner: “The 54th Massachusetts (negro), whom Copperhead officers would have called cowardly if they had stormed and carried the gates of hell, went boldly into battle, for the second time, commanded by their brave Colonel, but came out of it led by no higher officer than the boy, Lieutenant Higginson.” Sergeant James Henry Gooding of Company C of the 54th wrote weekly letters to the New Bedford Mercury, a periodical in the company’s hometown. Gooding’s letters were published as On the Altar of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front, and some are available on Google Books. Gooding’s July 20 letter documents the 54th’s attack of Fort Wagner: “When the men saw their gallant leader [Colonel Shaw] fall, they made a desperate effort to get him out, but they were either shot down, or reeled in the ditch below. One man succeeded in getting hold of the State color staff.” The “one man” who reached the flag was Sergeant William H. Carney, originally of Norfolk, Virginia, as he maintained the sanctity of the flag by keeping it from touching the ground. Though Carney was wounded in both of his legs, one arm, and his chest he kept the flag aloft and is recorded as exclaiming, “the old flag never touched the ground, boys!” During the 1897 monument dedication Carney raised the flag once more, an action that Booker T. Washington recorded in his autobiography, Up from Slavery (1901), as causing such an effect on the crowd that “for a number of minutes the audience seemed to entirely lose control of itself.” Three years later, Carney received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions at Fort Wagner. Though Carney is often listed as the first African-American recipient of the Medal of Honor, instead, Carney’s rescue of the colors at Fort Wagner was the earliest African-American act of bravery to be recognized with a Medal of Honor. The medal notation reads: “Medal of Honor awarded May 9, 1900, for most dinstinguished gallantry in action at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, July 18, 1863.”

Individual Stories

Front and Center: Some Who Served in the United States Colored Troops

“No officer in this regiment now doubts that the key to the successful prosecution of this war lies in the unlimited employment of black troops. Their superiority lies simply in the fact that they know the country, while white troops do not, and that they have peculiarities of temperament, position, and motive, which belong to them, alone. Instead of leaving their homes and families to fight they are fighting for their homes and families, and they show the resolution and sagacity which a personal purpose gives.”[1]

Approximately 180,000 African-Americans, comprising One Hundred sixty-three units, served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and many more served in the Union Navy. Native Americans served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT), while some, mainly in the south, fought for the Confederates. Black Indians, served in colored regiments with other African American and Native American soldiers.[2]

After the Civil War, many USCT veterans struggled for recognition and had difficulty obtaining the pensions rightful to them. The Federal government did not address the inequality until 1890 and many of the veterans did not receive service and disability pensions until the early 1900’s. My ancestors, Henry Green and Uriah Martin, applied for Pensions, and left documents of their lives before and after the Civil War. When it came to Henry Green, and Uriah Martin, my mother told us they came from the Welsh Mountains. She passed down what she was told, and we did not doubt that what she said was true. The census records and documents on our ancestors, are proof that her version was correct. She stated that, Uriah Martin’s brother, William Penn Martin settled in California after the Civil War.

I found information on a William Martin in Yolo County California, who was born in Pennsylvania. He fit the profile somewhat but I have not proved him to my satisfaction. I was thrown off by the racial designation of white on the 1870 census. There was another William Martin at Michigan Bar, in Sacramento, and he too was from Pennsylvania, and is listed as white. Great Uncle William Martin’s trail in California has grown cold, and remains a mystery to our family.

The Martin and Green men, lived closer to the land then Walter Samuel, and were a little more rugged. Henry Green had tattoos of Anchors on both forearms, a fact that was mentioned in his Civil War Records. They were remnants of the Natives, Free Blacks, and whites, who lived in and around the Welsh Mountains. The Welsh Mountain is a Community, which cuts through Lancaster and Chester County in Southeastern Pennsylvania. The Mountains were a place of refuge for escaped slaves, free blacks, and Natives avoiding deportation to reservations. Many of the whites who fled into the mountains were criminals, or running from Indentured Servitude. During Pennsylvania’s slave period, African slaves and indentured whites both sought freedom in the Mountains. They soon made up a rugged group, now known as, Tri-Racial Isolates.

My mother passed the history of our ancestors through stories she told, when we were children. It was a means of keeping us occupied during the cold Pennsylvania Winters. She spoke of the Civil War and our ancestors who were part of the Colored Troops. We learned about the Civil War in History Class, and looked through the books, for mention of the Colored Troop. There was no mention of them in the history books, nor in the books in our library. I knew that my mother would not make up tales about the family. It was not until 1983 that I ordered copies of Uriah Martin and Henry Greens Civil War Records. My mother and I poured over those records to glean information.

The Green and Martin families, were descendants of those rugged mountain folks, but lived in both worlds. They would come down and work on area farms and then head back to the mountains. In later years, the young people came down, married, and/or joined the Military. My Grandfather Martin was the last of our line to live in the Mountains. I remember going up there and seeing the haze over the trees. It was absolutely beautiful, and breathtaking, something that is hard to find words to describe. There were cases of people who wandered in the Welsh Mountains told Harrowing tales, of seeing Ghost like figures, and being shot at. There are even stories about people going in the Mountains and disappearing without a trace. These days there are only a few descendants, of the original people left on the Mountain. Developers have swept in, building upscale homes for Middle Class Families.

The Underground Railroad Colored Soldiers and the Welsh Mountains

My mother spoke about our Welsh Mountain ancestors, having been under the protection of William Penn. Her Paternal grandfather was named William Penn Martin, after his fathers brother, William Penn Martin Senior. They and their ancestors, considered themselves, “Penn’s Indians”, even after the land was taken, and most Natives were shipped to Reservations out west. They were the Conestoga and Susquehanna who lived along the Rivers and Creeks in Chester and Lancaster County.

The area where they hunted, and fished, was also part of the Underground Railroad, which led from Southern States like, Virginia and Maryland to points north. The Underground Railroad had many stops throughout Southeastern Pennsylvania, because of it’s proximity to the south. My Great-Great Grandfather, Robert Pinn, was one of the unsung heroes of the Underground Railroad. He and his family were free blacks living in Virginia, until 1853, when the fled to Columbia (Lancaster County), Pennsylvania. He was a vocal Baptist Minister in Virginia and continued to Minister in Columbia, until he was forced to flee to Burlington New Jersey. Robert Pinn was from a long line of Virginia’s Free Colored Population. His grandfather, Rawley Pinn was a Revolutionary War Soldier, who fought at The Siege of Yorktown. His wife, Elizabeth Jackson-Pinn, was also a descendant of Free Persons of Color, and her grandfather, Charles Lewis was a Sailor and Soldier during the Revolutionary War. Continue reading

Charles H. Parker, 3rd Regiment U.S.C.T.

(Essay written by Debra McCauslin — For the Cause Productions, Gettysburg, PA)

Charles H. Parker died in 1876 and was buried at Yellow Hill Cemetery near Biglerville in Adams County. Parker was born in Virginia and enlisted at age 18 at Chambersburg, PA. Parker served as a substitute for Washington Stover of Liberty Township, Adams County. Parker trained at Camp William Penn in Philadelphia and was mustered out October 31, 1865 at Jacksonville, Florida. Parker was 5 foot 11 inches tall and had been shot in the right leg while in service. He also contracted typhoid and pneumonia and became sickly within months of serving. After the war, he was feeble and complained of his bad health. He told neighbors he was weak and he coughed very much.

Charles Parker married Sarah Butler, daughter of Peter and Harriet Butler of Adams County, Menallen Township on November 7, 1867. The Parker’s lived in Flora Dale with a Garretson family in their tenant house in 1868. Charles and Sarah had several children: Mary Jane, born October 19, 1868; William, born May 22, 1871: Harriet born December 31, 1874 (she died at a young age); Elmer, born February 26, 1877,

His wife was seeking a pension for his service and Sarah Parker testified in 1895 that she and her children were living in York’s Gas Alley and they were “very poor and nearly starving to death.”

Parker’s remains were reinterred at the National Cemetery in Gettysburg in 1936 and no service was held Continue reading

William H. Mathews, 127th Regiment U.S.C.T.

(Essay written by Debra McCauslin — For the Cause Productions, Gettysburg, PA)

William H. Mathews of Adams County was born free in Pennsylvania in 1849.His parents were Edward and Annie (Gant) Mathews and originally from Carroll County, Maryland where they lived near Pipe Creek Friends (Quaker) Meeting until around 1839.

Edward Mathews is on the Adams County 1840 census as head of household with 6 others living with him. Edward purchased 16 acres of property in 1842 for $350 on Pine Hill, about a mile north of Biglerville. Biglerville is just 7 miles from Gettysburg and it is less than 20 miles from the Mason Dixon Line.

Pine Hill is known today as Yellow Hill. It is believed that the name, “Yellow” was given to the hill to reflect the skin tones of this early Negro family who were listed in the census with an “M” for mulatto. Yellow is a derogatory term used to define people of mixed races. The Mathews family lived there for several decades and through the 1890’s.

Edward Mathews was reputed to be involved in the Underground Railroad with nearby Quakers of Menallen Friends Meeting who lived below Pine Hill in the still-pristine Quaker Valley. Both Edward and Annie Mathews and William’s older brother Samuel were all born in Maryland. The other children were born in PA.

William Mathews enrolled in Co I, 127th USCT September 3, 1864. He was 15 when he enlisted. His brother Samuel was drafted. William and brother Nelson enlisted as well. Three Mathews brothers left Yellow Hill to go to Chambersburg where they were mustered in. They trained at Camp William Penn near Philadelphia. The regiment was incorporated into the Army of the James and participated at Deep Bottom. They were also posted on the Mexican frontier and they were mustered out at Bravos Santiago, Texas on September 8, 1865.

William married Mary Jane Walker on March 9, 1869. They had several children together. Mary Jane died in 1890. The Bendersville GAR issued a resolution and printed it in local newspapers “on the death of the wife of Comrad William H. Mathews.” It mentions sending sympathy to William and his family Continue reading

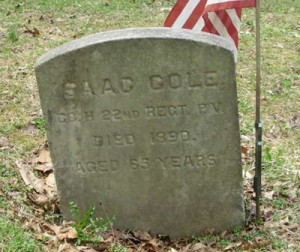

Isaac Cole, 32nd Regiment U.S.C.T.

(Essay written by Frank Hebblethwaite — Park Ranger, Hopewell Furnace NHS)

Abraham Lincoln referred to history as the “mystic chords of memory”. Those mystic chords of collective memory bind us together. Our common history connects us to each other in the present and to our ancestors in the past. It is a privilege to encounter those among us who instinctively recognize the importance of understanding and sharing their connections with the past in order to gain a fuller appreciation of who we are in the present.

Members of one family who have gained such an understanding of their past and have generously shared it with others are descendants of Isaac Cole, who enlisted in the Union Army in Reading, Pennsylvania on February 20, 1864 at the age of 40. The Mt. Frisby African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church Cemetery, where Isaac Cole is buried, is located on property that has been in the Cole family since the middle of the 19th century. John Cole, Isaac’s great-grandson, and his wife Barbara, who are the current owners of the property, have graciously allowed historians, park rangers, and other researchers to visit Isaac Cole’s burial site and to examine the words and dates chiseled on his government-issued headstone. They have also participated in numerous interviews so others might learn about their family history.

While little is known of Isaac Cole’s life prior to his enlistment into the Union Army, his military and census records have left us with a good deal of information about his life after he reported for duty to Camp William Penn in Philadelphia, where he was mustered into Company H, 32nd Regiment, United States Colored Troops.

The 32nd Regiment was ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina in April 1864 and remained on duty there until June of the same year. The regiment then moved to Morris Island, South Carolina, where they operated against Charleston. Between the end of November 1864 and the middle of February 1865, the men of the 32nd Regiment participated in an expedition to Boyd’s Neck, demonstrations on Charleston Camp, Savannah Railroad, Devaux’s Neck, and James Island, and the Battle of Honey Hill. After occupying Charleston from late February to the middle of April 1865, they took part in Potter’s Expedition, along with expeditions to Dingles’s Mills and Statesboro. Toward the end of April, the 32nd Regiment occupied Camden, Boydkin’s Mills, Beach Creek, and Denken’s Mills in rapid succession. The regiment then performed garrison duty at Charleston, Beaufort, and Hilton head, South Carolina until the middle of August. The 32nd Regiment was mustered out on August 22, 1865.

Isaac Cole’s application for an invalid pension, based on a foot injury he suffered while in camp in South Carolina, was rejected in 1887. Shortly after Isaac’s death in 1889, Continue reading

Descendants’ Profiles

These five descendants’ profiles were published in “Grand Review Times: A Call for the Descendants of USCT Troops from Camp William Penn 1863 to the Harrisburg Grand Review, 1865,” a supplement that appeared in the March 22, 2010 issue of ShowcaseNow! Magazine. You can read these profiles by clicking on the images below or by downloading the supplement. (Adobe Reader must be installed on your computer in order to read this document.)

These five descendants’ profiles were published in “Grand Review Times: A Call for the Descendants of USCT Troops from Camp William Penn 1863 to the Harrisburg Grand Review, 1865,” a supplement that appeared in the March 22, 2010 issue of ShowcaseNow! Magazine. You can read these profiles by clicking on the images below or by downloading the supplement. (Adobe Reader must be installed on your computer in order to read this document.)

Share your own story by adding a comment to this post or by emailing hdivided@dickinson.edu.

(Courtesy of visitpa.com & ShowcaseNow! Magazine)

[nggallery id=11]

Civil War Letters of John C. Brock

The book Making and Remaking Pennsylvania’s Civil War is a collection of essays about the events and legacies of the Civil War in Pennsylvania. The essay “The Civil War Letters of Quartermaster Sergeant John C. Brock, 43rd Regiment, United States Colored Troops,” edited by Eric Ledell Smith, focuses specifically on the issue of African-American troops from Pennsylvania. The first part of the chapter contains a synthesis of the history of African-American troops during the Civil War in general and specifically in Pennsylvania. The second part contains nine letters written by John C. Brock to the Christian Recorder, a newspaper published in Philadelphia by the African Methodist Church. Smith gives a good biography of Brock and explains the context and background of each letter. John C. Brock was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1843, and he enlisted in the army at Camp William Penn in April 1864. One of the exceptions to the general rule of not assigning colored regiments to combat duty, the 43rd regiment arrived in Virginia as part of the rear guard to the Army of the Potomac and Brock shared, “You cannot imagine with what surprise the inhabitants of the South gaze upon us.” Later, when his regiment proudly passed through Fairfax, Virginia “armed to the teeth, with bayonets bristling in the sun,” Brock echoed the same sentiment: , “The inhabitants… looked at us with astonishment, as if we were some great monsters risen up out of the ground.” His letters cover a wide range of topics, from religion to food and supplies to other African-American troops from Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, although his regiment was present at the Battle of the Crater, Brock does not mention it in his letters, and he also rarely elaborates on the issue of slavery, instead choosing to focus on topics more relevant to his everyday life in the army. His last letter in March 1865 briefly broaches the topic with eloquence and a great deal of optimism: “The hydra-headed monster slavery which, a few short years ago, stalked over the land with proud and gigantic strides, we now behold drooping and dying under the scourging lash of universal freedom…. The bondmen of the South have heard that single word ‘liberty,’ and they will not heed the siren voice of their humbled masters.” Brock is clearly proud to have had a part in defeating the South and the institution of slavery. These letters are a valuable resource for studying the Civil War from a perspective that is often overlooked, that of an African-American soldier in combat duty.

Medal of Honor Recipient — Sergeant William Carney

While William Harvey Carney was born a slave in Virginia in 1840, he escaped to freedom in Massachusetts through the Underground Railroad. He later enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and participated in the assault that took place in July 1863 on Fort Wagner in Charleston, South Carolina. Carney received a Medal of Honor in May 1900 for his actions during this battle. The citation for his Medal of Honor states: “When the color sergeant was shot down, this soldier grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back he brought off the flag, under a fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.”

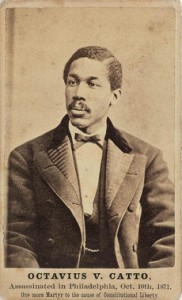

“Forgotten Black Hero of Philadelphia”

Temple University professor Dr. Andy Waskie has posted a useful profile of Octavius V. Catto, an ardent advocate for equal rights for blacks in Philadelphia during and after the Civil War. Catto was also instrumental in recruiting some of the first African American regiments for the Union army. He was assassinated in Philadelphia on an election day in 1871 while attempting to bring more African Americans to the ballot box.

Temple University professor Dr. Andy Waskie has posted a useful profile of Octavius V. Catto, an ardent advocate for equal rights for blacks in Philadelphia during and after the Civil War. Catto was also instrumental in recruiting some of the first African American regiments for the Union army. He was assassinated in Philadelphia on an election day in 1871 while attempting to bring more African Americans to the ballot box.

Catto was a fervent believer in the value of education, and founded the Banneker Literary Institute in Philadelphia to promote intellectual activism for young African Americans.

Waskie’s profile also describes roles played by pivotal figures in Catto’s life such as Union General Darius Nash Couch and fellow abolitionist Frederick Douglas.

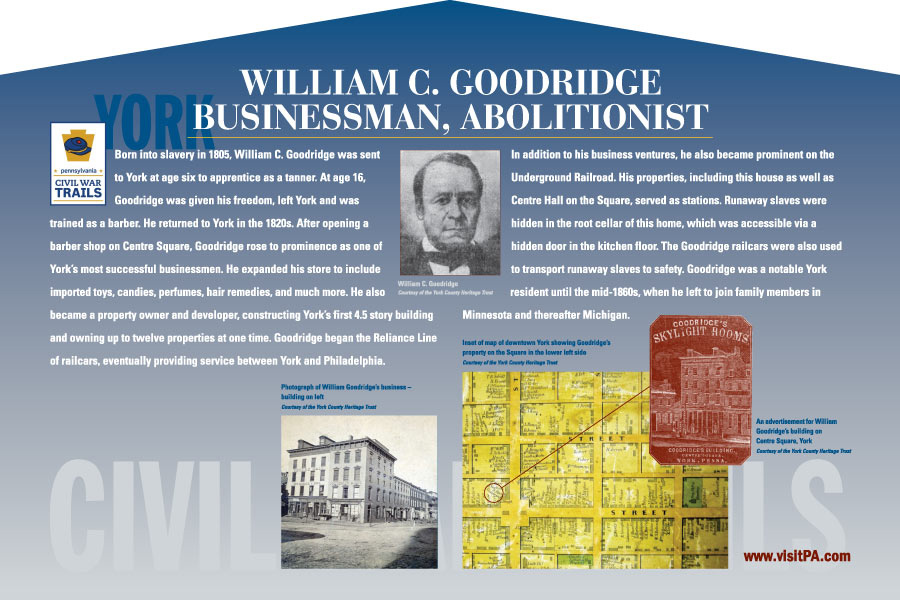

William C. Goodridge – Businessman & Abolitionist

William Goodridge, born into slavery, achieved freedom, business success and was a prominent figure in the Underground Railroad.

Address:

123 E. Philadelphia St.

YORK, PA, 17401

(Courtesy of Pennsylvania Civil War Trails)