Contributing Editors for this page include Jonas Sherr

Ranking

#111 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, December 14, 1861

The Lincoln Log, December 14, 1861

Close Readings

Jonas Sherr, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), September 15, 2013

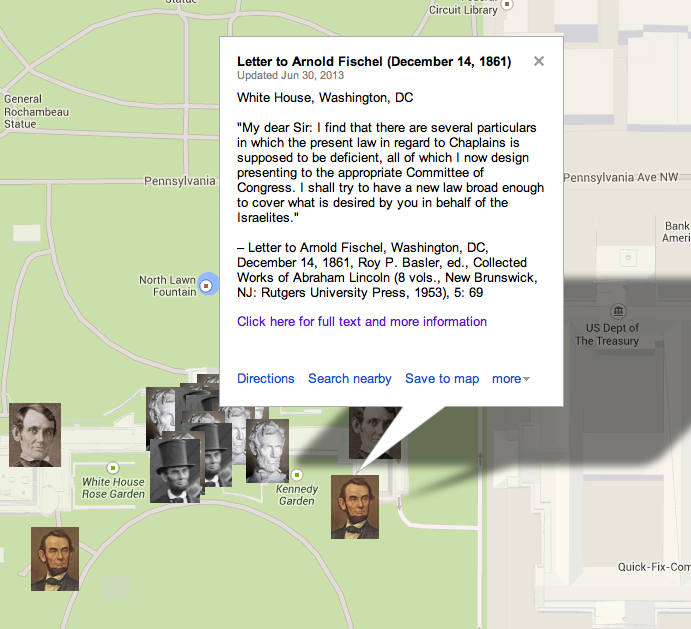

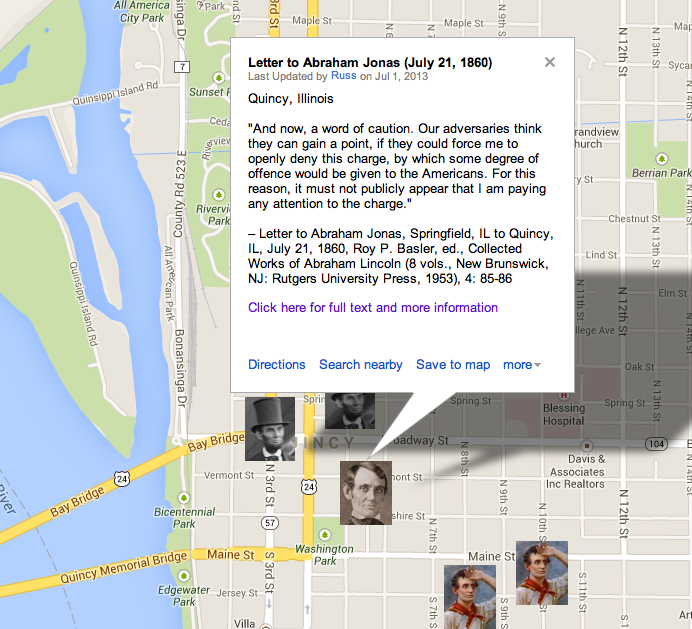

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“On December 6, 1861, the BODAI [Board of Delegates of the American Israelites] prepared a beautiful ‘Memorial,’ penned with a fair hand, addressed to the Senate and the House of Representatives. Presumably, Rabbi Fischel would carry this ‘Memorial’ to the nation’s capital. The tone of the remonstrance was firm. The document emphasized that the congressional act concerning military chaplains excluded from ‘the Office of Chaplain in the service of the United States ‘regular ordained ministers’ of the Jewish faith.’ The writers insisted that the current law was ‘prejudicial discrimination against a particular class of citizens, on account of their religious belief.’ Moreover, the law established a ‘religious test,’ which manifestly contravened the protections afforded the nation’s citizens by the Constitution. . .Despite reports to the contrary, President Lincoln agreed to see Rabbi Fischel on December 11, 1861. From Fischel’s perspective, the meeting went quite well. Lincoln even asked him to return the next day to discuss the matter further. . .On December 15, 1861, Rabbi Fischel received a short but gratifying letter from Abraham Lincoln. He sat down on the spot and penned a buoyant letter to Henry I. Hart (1816-1863), president of the BODAI. Fischel wanted Hart and the rest of the BODAI to read Lincoln’s words for themselves, so he quoted the entire text of Lincoln’s letter verbatim. Had the rabbi not done so, we might never have been able to document Lincoln’s personal involvement in the controversy, since the original of Lincoln’s note appears to have been lost. . .Lincoln kept his word. Five months later, Congress passed new legislation that would enable ministers of the Jewish faith to serve as chaplains in the U.S. military.”

“Hoping to create a test case based strictly on a chaplain’s religion and not his lack of ordination [as in the case of Michael Allen, an un-ordained Jewish minister who was fired from his chaplaincy post in 1861], Colonel Max Friedman and the officers of Cameron’s Dragoons then elected an ordained rabbi, the Reverend Arnold Fischel of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel, to serve as regimental chaplain-designate. When Fischel, a Dutch immigrant, applied for certification as chaplain, the secretary of war, none other than the Simon Cameron for whom the regiment was named, complied with the law and rejected his application. The rejection of Fischel finally stimulated American Jewry to action. The American Jewish press let its readers know that Congress had limited the chaplaincy to Christians and argued for equal treatment for Judaism before the law. This initiative irritated a handful of Christian organizations, including the YMCA, which resolved to lobby Congress against the appointment of Jewish chaplains. To counter their efforts, the Board of Delegates of American Israelites, one of the earliest Jewish communal defense agencies, recruited Reverend Fischel to live in Washington, minister to wounded Jewish soldiers in that city’s military hospitals and lobby President Abraham Lincoln to reverse the chaplaincy law. . . Armed with letters of introduction from Jewish and non-Jewish political leaders, Fischel met on December 11, 1861 with President Lincoln to press the case for Jewish chaplains. . . According to Fischel, Lincoln asked several questions about the chaplaincy issue, ‘fully admitted the justice of my remarks. . .and agreed that something ought to be done to meet this case.’ Lincoln promised Fischel that he would submit a new law to Congress ‘broad enough to cover what is desired by you in behalf of the Israelites.'”

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln