Ranking

#148 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“May I be pardoned if, upon this occasion, I mention that away back in my childhood, the earliest days of my being able to read, I got hold of a small book, such a one as few of the younger members have ever seen, ‘Weem’s Life of Washington.’ I remember all the accounts there given of the battle fields and struggles for the liberties of the country, and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton, New-Jersey. The crossing of the river; the contest with the Hessians; the great hardships endured at that time, all fixed themselves on my memory more than any single revolutionary event; and you all know, for you have all been boys, how these early impressions last longer than any others. I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for.”

On This Date

HD Daily Report, February 21, 1861

The Lincoln Log, February 21, 1861

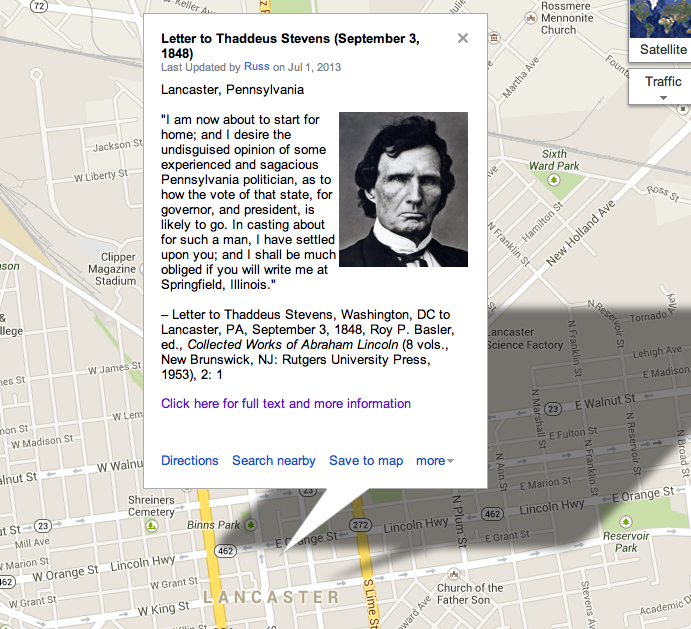

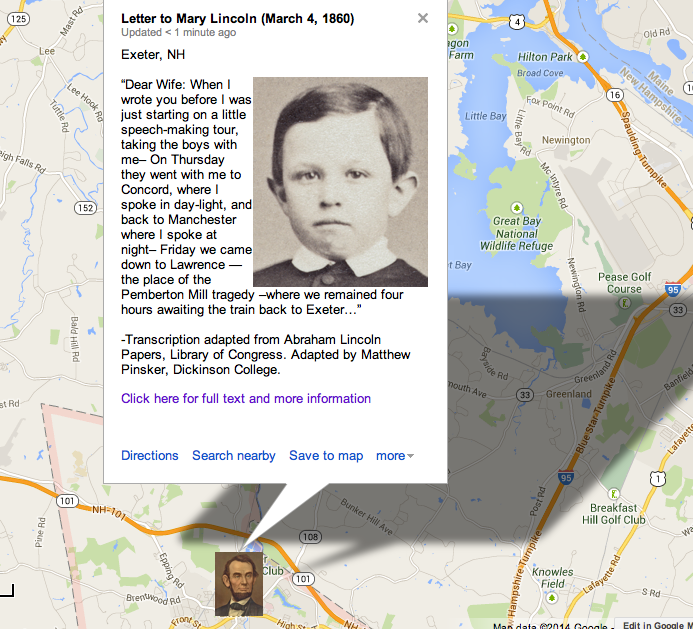

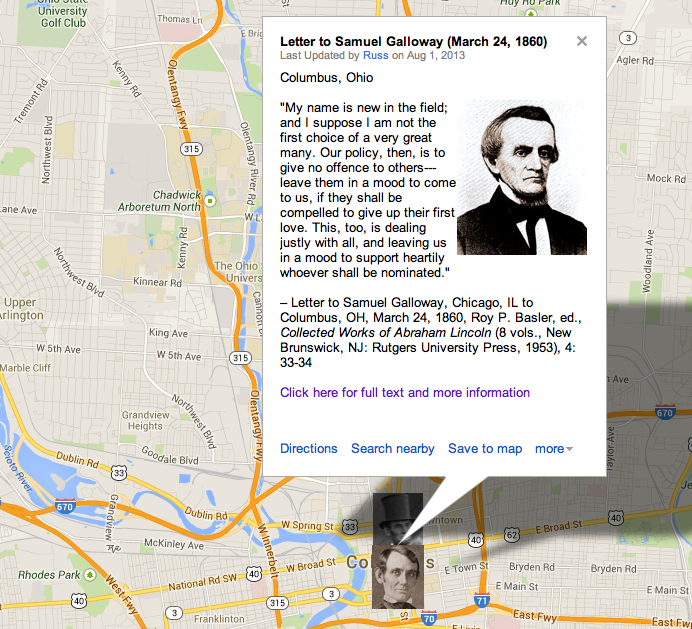

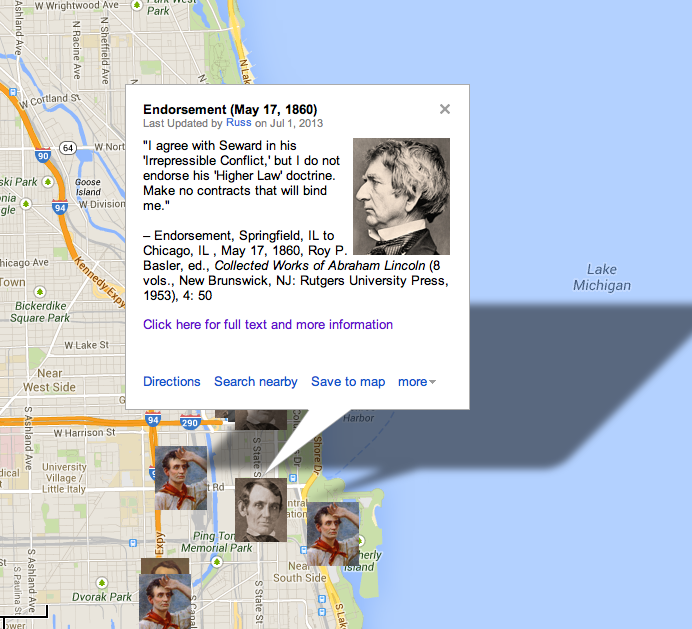

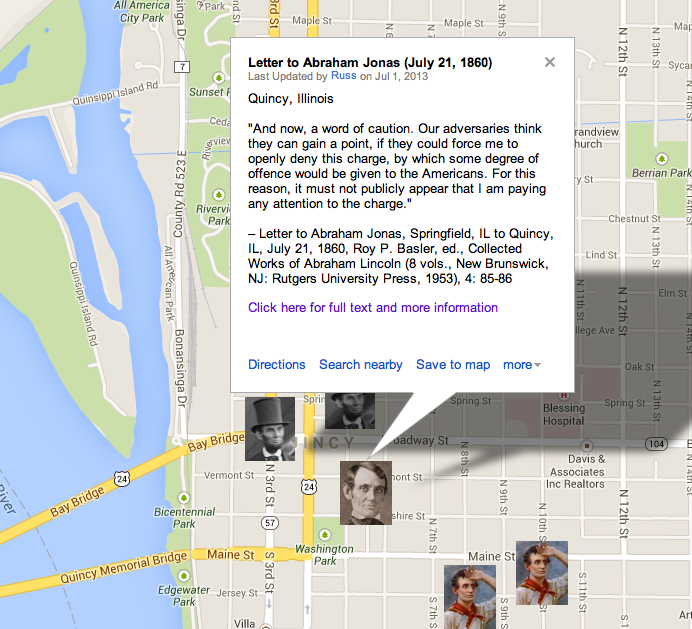

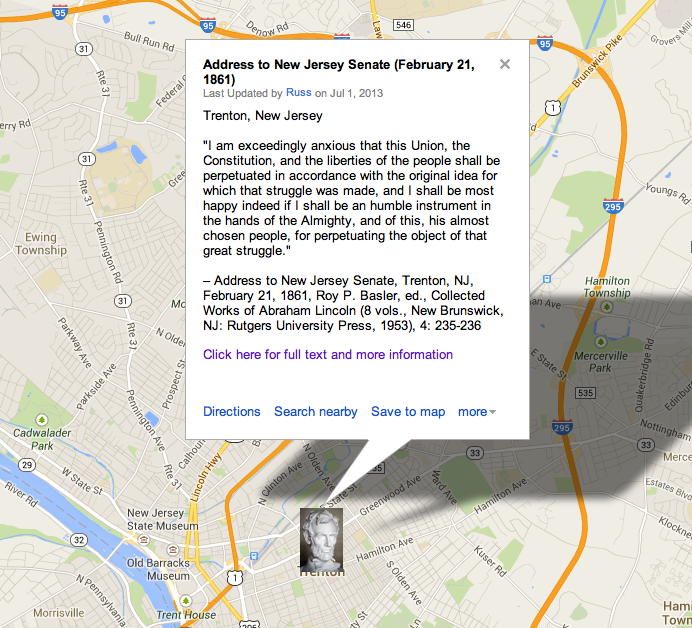

Custom Map

View in Larger Map

How Historians Interpret

“Finally, although he did once use the phrase ‘chosen people,’ referring to Americans, he did it in a radically different way from Beveridge and many others. Lincoln used the phrase when he spoke in the New Jersey Senate in Trenton on February 21, 1861, on the way to the White House. He spoke spontaneously, as he did not like to do; he remembered his youthful reading of ParsonPage Weems’ Life of Washington and his youthful belief that there was an ‘original idea’ beyond national independence. And he said that he himself would be most happy indeed if he could be ‘an humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty and of this, his almost chosen people.’ He added the modifier “almost” which changes the phrase completely. ‘And God did not say to Israel, You are almost my chosen people. I have nearly chosen you, from almost all the other peoples of the earth, to be unto me a somewhat special people.’”

–William Lee Miller, “Lincoln’s Profound and Benign Americanism, or Nationalism Without Malice,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 22, no. 1 (2001), 1-13.

“One of the first books he had read as a boy, Lincoln told the New Jersey senate in Trenton on February 21, 1861, was Parson Weem’s Life of Washington. Nothing in that book fixed itself more vividly in his mind than the story of the Revolutionary army crossing the ice-choked Delaware River in a driving sleet storm on Christmas night 1776, at a low point in the American cause, to attack the British garrison at Trenton. ‘I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for … something even more than National Independence … something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world for all time to come.’ This it was, said Lincoln next day at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, ‘which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance.’”

— James M. McPherson, “The Hedgehog and the Foxes,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 12, no. 1 (1991), 49-65.

“Before the New Jersey State Senate Lincoln reminisced about his youth: ‘away back in my childhood, the earliest days of my being able to read, I got hold of a small book, such a one as few of the younger members have ever seen, ‘Weem’s Life of Washington.’ I remember all the accounts there given of the battle fields and struggles for the liberties of the country, and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton, New-Jersey. The crossing of the river; the contest with the Hessians; the great hardships endured at that time, all fixed themselves on my memory more than any single revolutionary event; and you all know, for you have all been boys, how these early impressions last longer than any others. I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for. I am exceedingly anxious that that thing which they struggled for; that something even more than National Independence; that something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world to all time to come; I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made, and I shall be most happy indeed if I shall be an humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty, and of this, his almost chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle.’ As he prepared to leave the capitol, Lincoln was mobbed and ‘set upon as if by a pack of good natured bears, pawed, caressed, punched, jostled, crushed, cheered, and placed in imminent danger of leaving the chamber of the assembly in his shirt sleeves, and unceremoniously at that.’”

–Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 19 (PDF), 2145-2146

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

MR. PRESIDENT AND GENTLEMEN OF THE SENATE OF THE STATE OF NEW-JERSEY:

I am very grateful to you for the honorable reception of which I have been the object. I cannot but remember the place that New-Jersey holds in our early history. In the early Revolutionary struggle, few of the States among the old Thirteen had more of the battle-fields of the country within their limits than old New-Jersey. May I be pardoned if, upon this occasion, I mention that away back in my childhood, the earliest days of my being able to read, I got hold of a small book, such a one as few of the younger members have ever seen, “Weem’s Life of Washington.” I remember all the accounts there given of the battle fields and struggles for the liberties of the country, and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton, New-Jersey. The crossing of the river; the contest with the Hessians; the great hardships endured at that time, all fixed themselves on my memory more than any single revolutionary event; and you all know, for you have all been boys, how these early impressions last longer than any others. I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for. I am exceedingly anxious that that thing which they struggled for; that something even more than National Independence; that something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world to all time to come; I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made, and I shall be most happy indeed if I shall be an humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty, and of this, his almost chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle. You give me this reception, as I understand, without distinction of party. I learn that this body is composed of a majority of gentlemen who, in the exercise of their best judgment in the choice of a Chief Magistrate, did not think I was the man. I understand, nevertheless, that they came forward here to greet me as the constitutional President of the United States—as citizens of the United States, to meet the man who, for the time being, is the representative man of the nation, united by a purpose to perpetuate the Union and liberties of the people. As such, I accept this reception more gratefully than I could do did I believe it was tendered to me as an individual.