Contributing editors for this page include James Duncan

Ranking

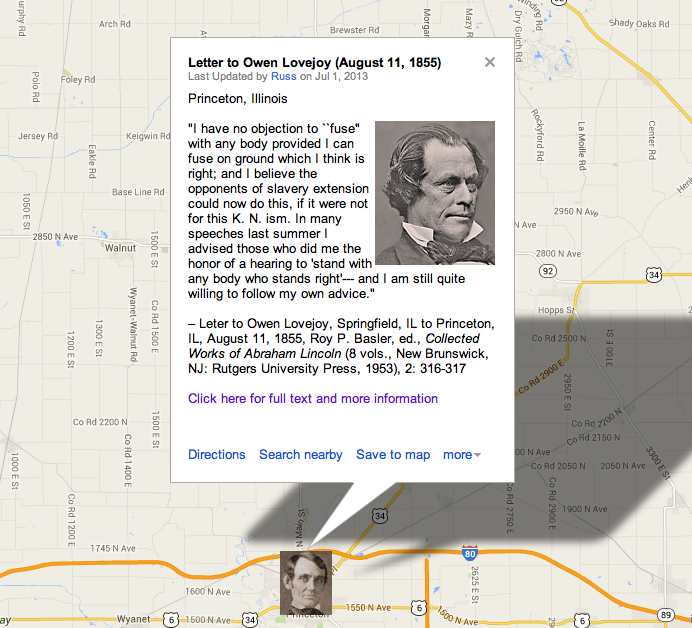

#96 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, August 11, 1855

The Lincoln Log, August 11, 1855

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” participant James Duncan, 2016

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“In Quincy at the end of July, the proselytizers managed to convince some western Illinois Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-Nebraska Democrats to band together on a platform opposing slavery expansion. When Lovejoy proposed that a state antislavery convention meet in Springfield that autumn, Lincoln replied that although he was ready to endorse the principles of the Quincy meeting, the time was not yet ripe for a new party. ‘Not even you are more anxious to prevent the extension of slavery than I,’ he told Lovejoy; ‘and yet the political atmosphere is such, just now, that I fear to do any thing, lest I do wrong.’ The Know Nothing organization had ‘not yet entirely crumbled to pieces,’ and until the antislavery forces could win over elements of it, ‘there is not sufficient materials to successfully combat the Nebraska democracy with.’ As long as nativists ‘cling to a hope of success under their own organization,’ they were unlikely to abandon it. ‘I fear an open push by us now, may offend them, and tend to prevent our ever getting them.’ In central Illinois, the Know Nothings were, Lincoln said, some of his ‘old political and personal friends,’ among them Joseph Gillespie of Edwardsville. Lincoln ‘hoped their organization would die out without the painful necessity of my taking an open stand against them.’ Of course he deplored their principles: ‘Indeed I do not perceive how any one professing to be sensitive to the wrongs of the negroes, can join in a league to degrade a class of white men.’ He was not squeamish about combining with ‘any body who stands right,’ but the Know Nothings stood wrong.”

–Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 1, Chapter 11 (PDF), 1159.

“In the political confusion between 1854 and 1856, anti-Nebraska elements often sought coalitions with Know-Nothings in efforts that became known as “fusion.” Antislavery candidates for Congress in 1854 often received nativist support. In Illinois, candidates in the third, fourth, and seventh congressional districts were greatly aided by Know-Nothing endorsements. Indiana editor and budding Republican politician Schuyler Colfax published anti-Catholic stories in his newspaper. There was some ideological affinity between free soil and nativism. One free-soil paper suggested that the “two malign powers”—Slavery and Catholicism—”have a natural affinity for each other.” On the other hand, many anti-Nebraska leaders deplored the bigotry inherent in the Know-Nothings and were fearful of alienating the crucial support of Protestant Germans.”

–Mitchell Snay, “Abraham Lincoln, Owen Lovejoy, and the Emergence of the Republican Party in Illinois,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 22, no. 1 (2001): 82-99.

“The failed Senate election of 1855 forced Lincoln to reexamine his resistance to fusion and to ask whether, once gain, his passion for loyalty had kept him loyal to a losing proposition… when Lovejoy urged Lincoln in August, 1855, to join a ‘fusion’ movement in Illinois, Lincoln patiently explained that ‘not even you are more anxious to prevent the extension of slavery than I,’ but still ‘the political atmosphere is such, just now, that I fear to do any thing, lest I do wrong.’ Later that month, he told Joshua Speed that as far as he was concerned, ‘I think I am a Whig.’ But there were voices all around him which argued that ‘there are no whigs, and that I am an abolitionist, which was just the kind of radical association that any fusion movement was likely to taint him with. One thing which was ‘certain,’ he told Speed, was that he was ‘not a Know-Nothing’ Lincoln ‘opposed Know-Nothingism in all its phrases, everywhere, and at all times when it was sweeping over the land like wildfire,’ Herndon remarked. As Lincoln told Lovejoy, ‘I do not perceive how anyone one professing to be sensitive to the wrongs of negroes, can join in a league to degrade a class of white men.’ Without any identifiable religion of his own, Lincoln shared none of the anxieties of Whig Protestants about ‘political Romanism,’ and found the Know-Nothings, even more than the Calhounites, a standing repudiation of what ‘as a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’’ That had not prevented the Know-Nothings from trying to recruit him in 1854 as a state legislative candidate, and rumors that he had secretly taken the Know-Nothing oath cost him at least one critical vote in the 1855 senatorial election. If this was the future of fusion, Lincoln was better off staying a Whig, for what that might be worth.”

–Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), 201-202.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text