Ranking

#123 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, November 10, 1854

The Lincoln Log, November 10, 1854

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

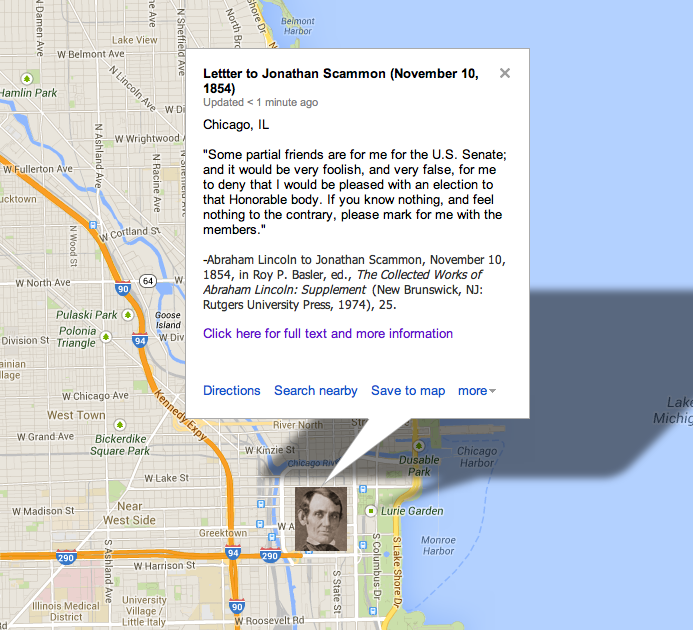

“Lincoln, Herndon recalled, was ‘ambitious to reach the United States Senate, and, warmly encouraged in his aspirations by his wife,’ campaigned for the post with ‘his characteristic activity and vigilance. During the anxious moments that intervened between the general election [in November] and the assembling of the Legislature [in January] he slept, like Napoleon, with one eye open.’ Three days after the November election, Lincoln began writing a torrent of letters asking support for his senate bid. On November 10, he appealed to Charles Hoyt of Aurora: ‘You used to express a good deal of partiality for me; and if you are still so, now is the time. Some friends here are really for me, for the U.S. Senate; and I should be very grateful if you could make a mark for me among your members.’ That same day, he told Jonathan Y. Scammon of Chicago that ‘Some partial friends here are for me for the U.S. Senate; and it would be very foolish, and very false, for me to deny that I would be pleased with an election to that Honorable body. If you know nothing, and feel nothing to the contrary, please make a mark for me with the members.’ The following day he asked Jacob Harding of Paris to visit his legislator and “make a mark with him for me,’ for ‘I really have some chance.’ Later that month, he appealed to Thomas J. Henderson of Toulon: ‘It has come round that a whig may, by possibility, be elected to the U.S. Senate; and I want the chance of being the man. You are a member of the Legislature, and have a vote to give. Think it over, and see whether you can do better than to go for me.’ The following month, he wrote Joseph Gillespie: ‘I have really got it into my head to try to be United States Senator; and if I could have your support my chances would be reasonably good.'”

“Lincoln was dismissive of nativism at least in private, and most of his biographers have quoted a handful of his now famous letters to figures such as political activist Owen Lovejoy and old friend Joshua Speed in the mid-1850s that contained some moving denunciations of nativist prejudice. Yet the new documents from the post-Collected Works period also illustrate how Boss Lincoln was also apparently able to compartmentalize his personal views whenever it came to the necessities of managing the party machinery. Lincoln’s outreach to Know Nothings, Americans, and former Fillmore men was not only persistent but also at times subtle. Consider this rarely cited 1854 note from the First Supplement (1974) to Chicago attorney and businessman Jonathan Y. Scammon. . . ‘If you know nothing, and feel nothing to the contrary.’ Such a confidential double entendre might have been a mere coincidence, but most likely it was a clever pun intended to create some ambiguity as to whether or not Lincoln was kidding around or trying to signal implicit sympathy with the Know Nothings. Scammon cautiously declined to answer in writing, promising instead to ‘communicate personally.’ Scammon’s ties to the nativist movement, if any, remain murky, although all that really matters here is what Lincoln might have believed.”

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln