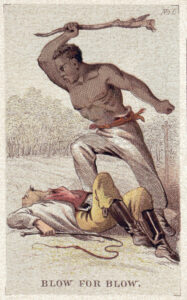

Freedom seekers fire upon a posse of whites at Christiana, Pennsylvania in September 1851. (House Divided Project)

Armed with “pistols and tomahawks,” a group of 10 freedom seekers refused to surrender to their white pursuers. It was late May 1845, and they had been overtaken by 8 white men near Smithsburg, Maryland. Ordered to halt, the freedom seekers instead “drew themselves up in battle order,” and “immediately commenced an attack upon the whites, felling several of them to the earth.” What followed was a “desperate contest,” in which two enslaved people were recaptured, and three white men were severely wounded. Bloodied but still defiant, the remaining freedom seekers continued northward towards freedom. [1]

This and numerous other bloody episodes are recounted in Stanley Harrold’s invaluable book, Border War (2010). As its title suggests, Harrold’s work chronicles the struggles over slavery along the North-South border in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Harrold contends that disputes over slavery were magnified in these contentious border regions, where the possibility of escapes was the highest. He recites a long string of armed conflicts between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces that escalated to a fever pitch by the 1850s. Harrold argues that these violent borderland encounters spurred on the secessionist movement much farther away, asserting that “fear in the Lower South of losing the Border South was a major cause of the Civil War.” [2]

For the scope of this project, Harrold’s focus on armed conflict is especially important. Not only does he dismantle the stereotype of passive, non-violent abolitionists, but he applies the same lens to escaping slaves, whom he insists were far from “peaceful.” Freedom seekers, he adds, “often carried weapons and fought masters who pursued them.” [3]

Wartime image depicting a freedom seeker resisting a white slaveholder. (House Divided Project)

In reframing escaping slaves as aggressive actors, Harrold makes an important contribution to our understanding of slave stampedes, even though he generally avoids the term. Still, Harrold documents multiple “mass-escapes,” which he notes “could appear much like [a] revolt,” and often ended in bloodshed. The first case he mentions comprised a group of 70-80 enslaved men from southern Maryland, partially armed, who defiantly headed northward in July 1845. They were eventually overtaken by a large posse of over 300 whites, who quickly shot and wounded nine of the escaped slaves and recaptured the remaining freedom seekers. While only two slaves faced legal consequences (including one freedom seeker who was sentenced to death), most were sold to the Deep South as punishment for their involvement. [4]

Harrold continues by detailing a similar escape in Kentucky in 1848, which involved anywhere from 40-70 enslaved men, fully equipped with “guns, pistols, knives and other warlike weapons.” The freedom seekers “fortified” their overnight encampment near the Ohio River, where they were ultimately attacked in what was described by newspaper reports as a “battle,” that resulted in the death of one enslaved man and one white man. Surrounded, the freedom seekers surrendered, but in this instance Kentucky officials brought over 40 of the escapees to trial. A white college student who had accompanied them was sentenced to 20 years of hard labor at the state penitentiary, while three slaves identified as leaders in the effort were convicted and hanged. Most, however, would be returned to their slaveholders, who could dole out punishment as they saw fit. [5]

Yet what Harrold describes as the “most influential mass-escape attempt” occurred in the shadow of the nation’s capitol in April 1848. Orchestrated by abolitionist newspaperman William L. Chaplin and a free black man named Daniel Bell, the pair arranged for 77 slaves in Washington, D.C. to board a boat which they had chartered and sail down the Potomac River toward freedom. However, the party encountered winds and was soon overtaken by a pursuing ship and easily recaptured. Known as the Pearl escape (after the name of the escapees’ vessel), the incident became an instant political lightning rod, infuriating pro-slavery politicians. [6]

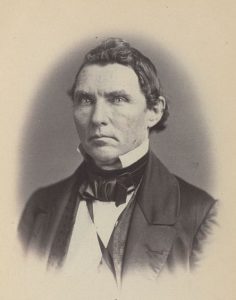

Future congressman Thomas Lilbourne Anderson decried the effects of slave stampedes at an 1853 anti-abolition meeting in Palmyra, MO. (Library of Congress)

Border War‘s coverage of Missouri is relatively light, though Harrold does reference an important pro-slavery meeting held at Palmyra in Marion County, near the Illinois border. The gathering came on the heels of a recent stampede, in which around 11 enslaved people had escaped from Marion County across the border into Illinois. A local Missouri politician, Thomas L. Anderson, accused abolitionists of orchestrating the stampede and others like it. Using rhetoric that underscored the chilling effect such escapes, Anderson estimated that stampedes cost fellow slaveholders “eight or ten thousand dollars worth” of enslaved property “at a time.” [7]

While mass escapes and their often violent nature are clearly a recurring concept in Border War, the actual term “slave stampede” appears just twice. In one instance, he uses the term to refer to the mass escapes which became increasingly common in the early 1850s, briefly noting examples in Maryland and Kentucky, as well as a group of some 70 freedom seekers who made their way through Illinois in August 1853. Later in the book, Harrold quotes a Baltimore editorialist, writing in the midst of the “Secession Winter” of 1860-1861, who cautioned that Maryland’s border state status made leaving the Union a particularly precarious prospect. If the state seceded, he predicted, “then will commence the stampede” which would effectively end slavery in “less than six months.” [8] As a whole, however, Harrold’s book adds immense value to our understanding of slave stampedes, demonstrating that mass escapes were frequently violent, and often took on a revolutionary meaning.

[1] “Runaway Negroes–A Battle with the Whites,” Boston Daily Atlas, June 2, 1845.

[2] Stanley Harrold, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 1-13.

[3] Harrold, 14.

[4] Harrold, 36, 129-131.

[5] Harrold, 131.

[6] Harrold, 131-133.

[7] Harrold, 161-162; Benjamin G. Merkel, “The Underground Railroad and the Missouri Borders, 1840-1860,” Missouri Historical Review 37:3 (April 1943): 278, [WEB].

[8] Harrold, 145-146, 199.