On August 30, 1854, the Daily Missouri Republican responded to a rash of slave escapes in St. Louis by publishing a sensationalized story about the “Underground Railroad” and its supposedly well-organized network of abolitionists who were engaged in “negro-stealing,” as the leading Democratic journal bitterly put it. According to historian Larry Gara, this exposé then set off a furious back-and-forth between pro- and anti-slavery newspapers in the city, a debate that highlighted the polarizing nature of slave escapes.[1]

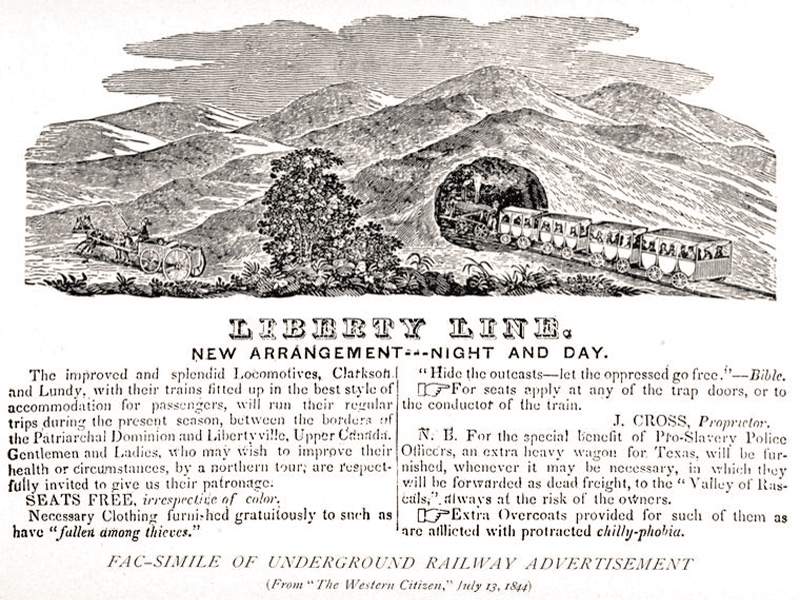

Larry Gara’s pioneering book, The Liberty Line (1961) uses propaganda battles like the one among St. Louis newspapers in the summer of 1854 to help explain the origins of some myths about the Underground Railroad. Gara was one of the first scholars to expose some descriptions of the Underground Railroad as folklore. His work claims that the Underground Railroad was more localized than its national romantic legend and that escapes from slavery were far more spontaneous and self-motivated than any kind of by-product of organized help from white abolitionists.[2]

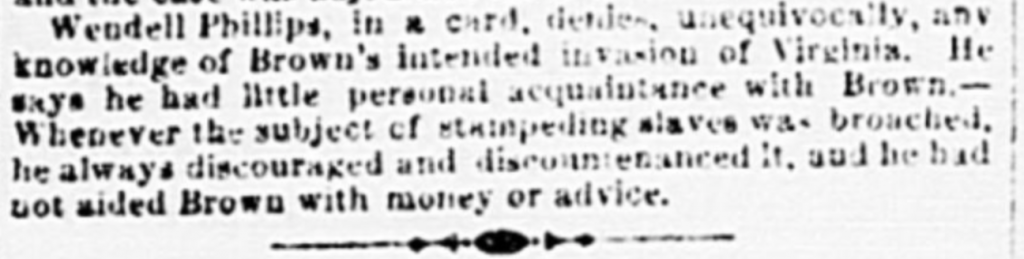

Gara uses the term “stampede” or its variants at least twice in his work, once when describing how “there were veritable epidemics of slave escapes from time to time,” adding, “Southern papers referred to group escapes as stampedes.” [3] The second time, Gara provides a revealing paraphrase from Wendell Phillips, when the controversial Boston abolitionist denied any responsibility for John Brown’s 1859 raid because (in Gara’s words), “he had always discouraged and discountenanced the idea of stampeding slaves.” [4] In addition, Gara’s text occasionally refers to various group or mass escapes without explicitly labeling them as stampedes.

Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1859 (Chronicling America)

Gara often focuses on such group escapes when attempting to debunk popular myths that portray Quakers as the main actors helping fugitive slaves; Gara’s description of an 1856 family escape from Kentucky highlights a different reality. In 1856, a former slave living in Ohio returned to Kentucky to help guide his enslaved wife and children north to freedom. The former slave led his family and three others to freedom without encountering any help until reaching the free state of Indiana. In Indiana, the group finally met Quakers who fed them, gave them money, and forwarded them along the underground railroad. Despite this help, the fugitives were clearly on their own for the most dangerous part of their journey. [5]

The Liberty Line focuses on restoring black agency when describing the nature of fugitive slave escapes. In the years since the publication of this landmark work in 1961, there have been many other works that have also emphasized the agency of both enslaved and free blacks. One goal of this project on slave stampedes will surely be to continue to seek out such examples and evidence of black resistance, organization, and power in the process of securing freedom.

[1] Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad (Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press, 1961), 157.

[2] Jennifer Schuessler, “Words From the Past Illuminate a Station on the Way to Freedom,” New York Times, January 14, 2015, [WEB]

[3] Gara, 22.

[4] Gara, 88. Gara cites this claim by Phillips to the Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1859.

[5] Gara, 59.