Daniel Drayton, captain of The Pearl, arrested in 1848, received a pardon in 1852

The Pearl incident was one of the largest attempted mass slave escapes in American history. On April 15, 1848, more than 70 enslaved people, including many children, boarded a schooner named The Pearl on the Potomac River in Washington, DC, in a daring effort organized after weeks of “preconcerted planning,” as scholar Andrew Delbanco puts it in The War Before the War (Nov. 2018), managed by an impressive network of free African Americans, white abolitionists, and the enslaved themselves. The effort was shocking to many of their opponents. Delbanco writes memorably in his new book about the fugitive crisis, that slaveholders in Washington awoke to find “Breakfasts were not ready, babies were not dressed, horses and chickens were going hungry; nobody was performing the morning tasks expected of urban slaves.” [1]

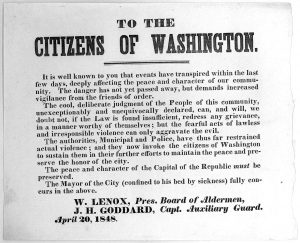

The freedom seekers, however, did not get far. Poor sailing conditions forced the ship to dock 150 miles down the Potomac, where officials soon boarded the ship, recaptured the freedom seekers and arrested three white men who helped them escape. The failed escape’s size and proximity to the nation’s capitol exacerbated slaveholder fears about slave resistance, rebellion, and violence. While the Pearl escape was itself nonviolent, the jarring nature of the event made the threat of slave resistance seem ever more palpable in the slaveholder’s imagination.

1848 poster made by the District of Columbia government shortly after the Pearl Escape, courtesy of wikepedia.org

Delbanco uses the Pearl incident as part of his wide-ranging effort to explain how the long crisis over fugitive slaves in the United States was a key dynamic behind the rising sectional tensions that ultimately led to the American Civil War. He describes the incident as the “capstone event of a decade during which the nation moved closer and closer towards a decisive confrontation with itself.” [2]

Delbanco does not use the term “stampede” to describe the 1848 event, nor does he apply that terminology to other types of group or mass escapes that he relates in his gripping narrative. However, the noted scholar from Columbia University routinely employs phrases such as “group escape,” “maroons” and “mass exodus” when detailing larger bodies of freedom seekers escaping bondage together. Nor does Delbanco focus explicitly on Missouri or the Mississippi Valley, but his work is still immensely helpful in contextualizing aspects of this project. He does mention, for example, that the “sheer volume of absconding slaves was immense” from the border state of Missouri. [3] He also explains how being a “slave in, say, St. Louis or Baltimore …meant better prospects for escape.” [4] Although group escapes sometimes occurred in the deeper South or within interior regions, he details how they more often resulted in movement toward life as “maroons” hiding in “cleared ground and the swamp or forest beyond” for extended periods of time. [5]

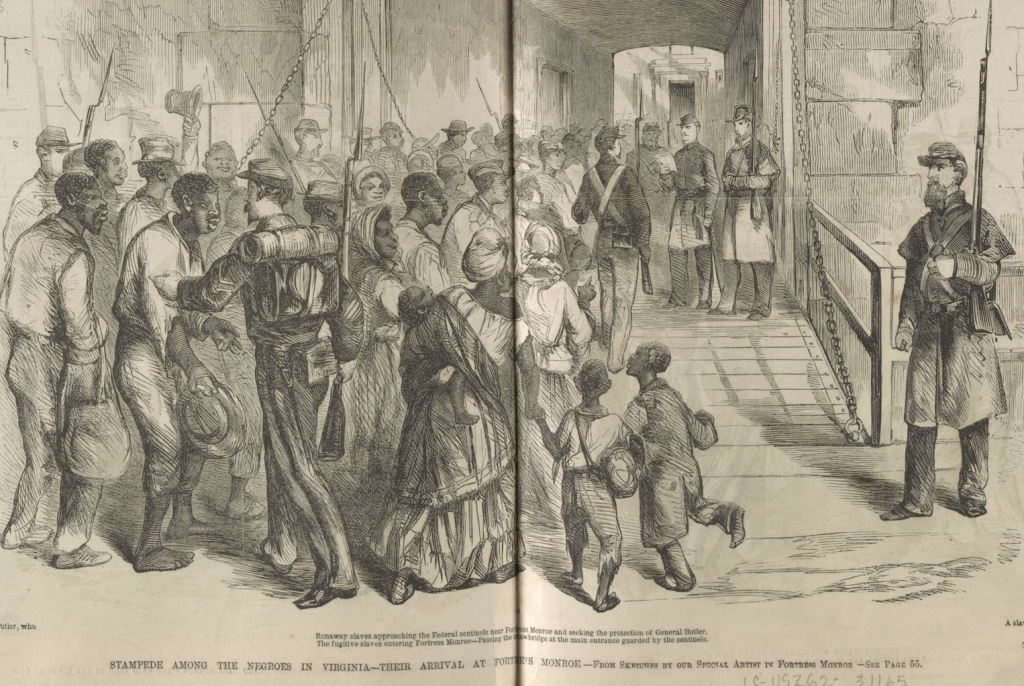

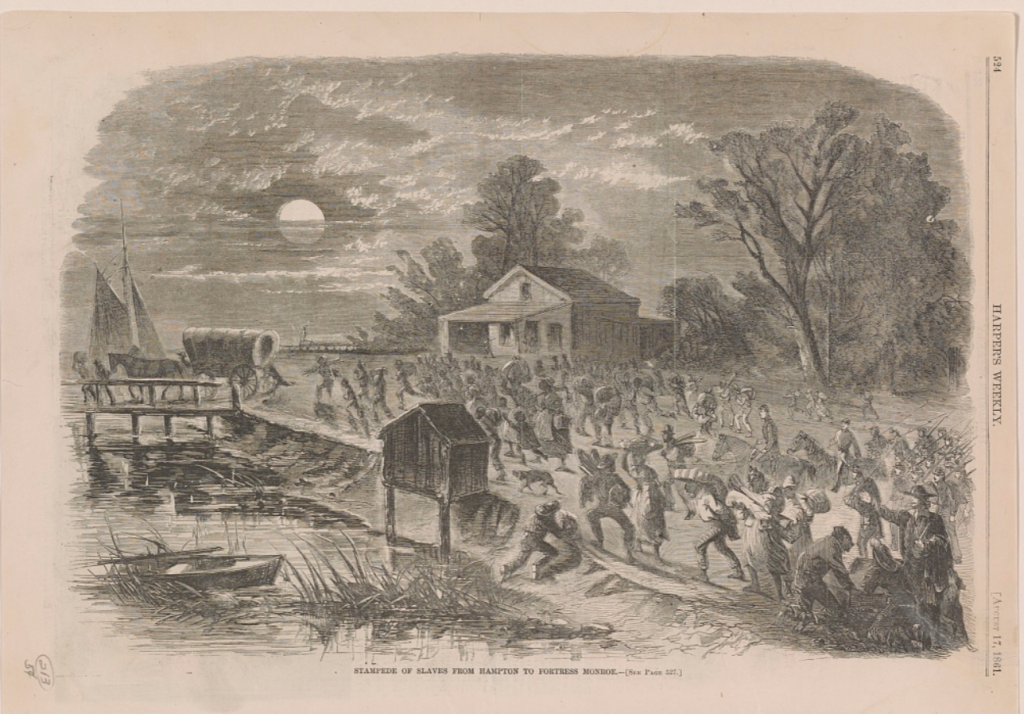

The term “stampede” does appear in Delbanco’s new book though in contexts different from antebellum mass escapes. When describing the impact of the pivotal Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, for example, Delbanco writes that it “set off a stampede of enraged adversaries.” The scholar also uses a memorable image from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in June 1861, captioned originally as “Stampede Among the Negroes in Virginia,” This vivid cartoon predated a more famous one that appeared in Harper’s Weekly in August 1861, captioned, “Stampede of Slaves from Hampton to Fortress Monroe.” Both illustrations from the summer of 1861 depicted the emergence of wartime runaways or contrabands at the very outset of the war. And ultimately, that is Delbanco’s point. The resistance of runaway slaves, especially through stampedes or various types of group or mass escapes, had an outsized impact on the paranoia of slaveholders. “Black violence was always lurking- at least in the white mind. And no matter how much whites wanted to believe that blacks were passive under the putatively benign regime of slavery, fugitives and rebels were a continual rebuke to this belief,” argues Delbanco. [6]

[1] Andrew Delbanco, The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War (New York: Penguin Press, 2018), 214.

[2] Delbanco, 215.

[3] Delbanco, 25.

[4] Delbanco, 35.

[5] Delbanco, 109.

[6] Delbanco, 199.