Contributing Editors for this page include Andrew Villwock

Ranking

#132 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, November 2, 1863

The Lincoln Log, November 2, 1863

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” Andrew Villwock, Fall 2013

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

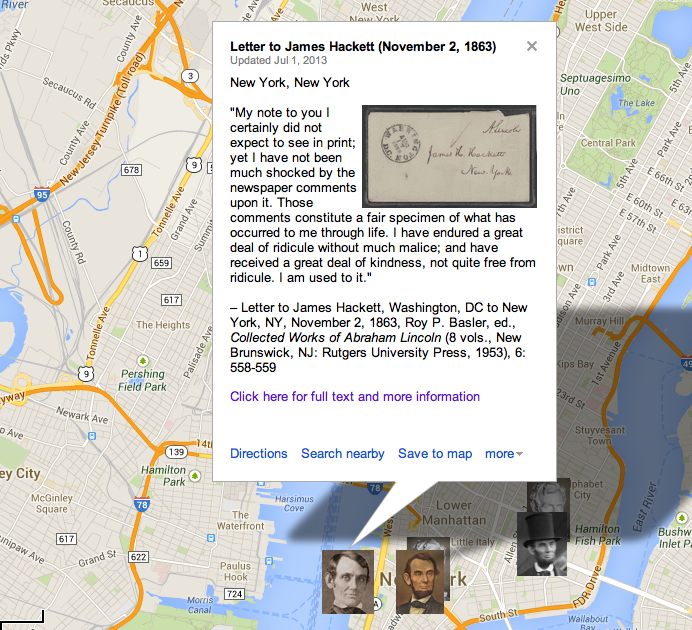

“Of all the clamorous horde, none dismayed Lincoln more than the eminent Shakespearean actor, James H. Hackett. After seeing Hackett play Falstaff, the president wrote him a fan letter. The indiscreet actor allowed it to get into the hands of newspapers, including the New York Herald, which ridiculed Lincoln’s taste in soliloquies. Abashed, Hackett apologized to Lincoln, who replied: ‘Give yourself no uneasiness on the subject. . . . My note to you I certainly did not expect to see in print; yet I have not been much shocked by the newspaper comments upon it. Those comments constitute a fair specimen of what has occurred to me through life. I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice; and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule. I am used to it.’ The friendly correspondence between them ended when Hackett asked for a diplomatic post that could not be given. John Hay recalled that a ‘hundred times this experience was repeated: a man would be introduced to the President whose disposition and talk were agreeable; he took pleasure in his conversation for two or three interviews, and then this congenial person would ask some favor impossible to grant, and go away in bitterness of spirit.’”

–Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 35 (PDF), 3868.

“That same year, the celebrated Shakespearean actor James Hackett made public a letter from Lincoln in which the Shakespeare-loving president un-inhibitedly identified his favorites among the Bard’s play and soliloquies. Perhaps aware that Hackett was a longtime friend of his rival Henry Raymond, Bennett pounds on the letter, editorializing: ‘Mr. Lincoln’s genius is wonderfully versatile. No department of human knowledge seems unexplored by him. He is equally at home whether discussing divinity with political preachers, debating plans of campaign with military heroes, [and] illustrating the Pope’s bull against the comet to a pleasure party from Chicago… It only remained for him to cap the climax of popular astonishment and admiration by showing himself to be a dramatic critic of the first order, and the greatest and most profound of the army of Shakespearean commentators.’ When Hackett wrote Lincoln to apologize for inadvertently giving the Herald and opportunity to taunt him, Lincoln assured him that he need not worry. Shrugging off his long years of experience as a target of newspaper mockery, Lincoln sighed: ‘I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice; and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule. I am used to it.’”

–Harold Holzer, Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014), 482-483.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln