Biographical Profiles - The Underground Railroad

| William Baylis was one of the few underground members to assist fugitives even as he turned a profit. Baylis was a Delaware schooner captain who assisted fugitive slaves by removing them from the Virginia coastline to freedom for a fee. Baylis and the Keziah, his schooner, were active until his capture in 1858. For his “offenses,” Baylis was sentenced to 40 years in prison but served only 6 years of the sentence whereupon Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, pardoned Baylis. Baylis ended his days as a grocer in Delaware. |

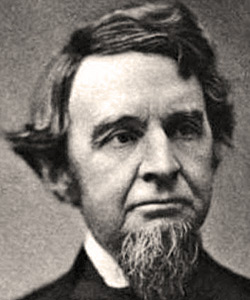

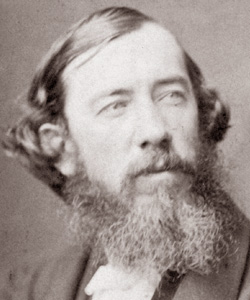

| Jacob Bigelow, a lawyer, stepped in to resurrect Washington's Underground when its tireless leader, William Chaplin, was arrested. Bigelow, like many members of the underground, participated in the day-to-day toil of the underground even as he organized the work and movements of others. Once, he smuggled a young slave girl to freedom by dressing her as a boy. Additionally, he corresponded with the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee under the apt nom de plume “William Penn.” The bulk of his correspondence provides evidence that Bigelow had regular contact with covertly operating underground conductors, and that a more expansive underground network than historians have previously allowed, may have existed. |

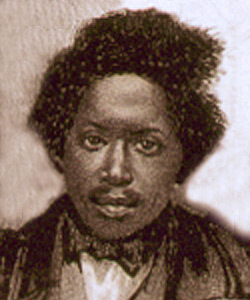

In 1849, Virginia slave Henry Brown (1815-???) escaped to freedom in such a way that he became an immutable subject of Underground Railroad lore. Brown was both a well-treated and skilled slave; however, he became virulently dissatisfied with slavery when his family was sold. Brown befriended Samuel Smith, a merchant, who observed that Brown's skill with tobacco could sustain him as a free man. Brown made up his mind to escape, and with assistance from a sympathetic free black, constructed a box with dimensions 3 feet by 2 feet by 2 feet. Brown secretly contacted the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery office, and enigmatically alluded to the pending arrival of a box that should be immediately opened. Brown then shipped himself, in the box, to the office. He arrived alive, and now, free, having endured a trek of 350 miles with 3 air holes and minimal provisions. His creative escape earned him the name, Henry “Box” Brown. J. Miller McKim and William Still of the Anti-Slavery Office were among those present at Brown's "resurrection." In 1849, Virginia slave Henry Brown (1815-???) escaped to freedom in such a way that he became an immutable subject of Underground Railroad lore. Brown was both a well-treated and skilled slave; however, he became virulently dissatisfied with slavery when his family was sold. Brown befriended Samuel Smith, a merchant, who observed that Brown's skill with tobacco could sustain him as a free man. Brown made up his mind to escape, and with assistance from a sympathetic free black, constructed a box with dimensions 3 feet by 2 feet by 2 feet. Brown secretly contacted the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery office, and enigmatically alluded to the pending arrival of a box that should be immediately opened. Brown then shipped himself, in the box, to the office. He arrived alive, and now, free, having endured a trek of 350 miles with 3 air holes and minimal provisions. His creative escape earned him the name, Henry “Box” Brown. J. Miller McKim and William Still of the Anti-Slavery Office were among those present at Brown's "resurrection." |

In 1814 Levi Coffin (1798-1877), a Quaker and North Carolina native, his father Vestal and brother Addison, helped to found the North Carolina Manumission Society. In 1818, the Society merged with the American Colonization Society. Rejecting the notion that slaves should be removed to Africa to obtain freedom, the Coffins separated themselves from the Society to take more decisive action. The Coffins began by helping only kidnapped slaves escape to freedom but progressed to assisting any fugitive slave. Their efforts acted at the genesis of the Underground Railroad in North Carolina . But by 1825, anti-Quaker sentiment had grown so predominant that the Coffins moved to Richmond, Indiana . There they established an underground that operated ceaselessly for decades. In 1814 Levi Coffin (1798-1877), a Quaker and North Carolina native, his father Vestal and brother Addison, helped to found the North Carolina Manumission Society. In 1818, the Society merged with the American Colonization Society. Rejecting the notion that slaves should be removed to Africa to obtain freedom, the Coffins separated themselves from the Society to take more decisive action. The Coffins began by helping only kidnapped slaves escape to freedom but progressed to assisting any fugitive slave. Their efforts acted at the genesis of the Underground Railroad in North Carolina . But by 1825, anti-Quaker sentiment had grown so predominant that the Coffins moved to Richmond, Indiana . There they established an underground that operated ceaselessly for decades. |

In December 1848, William (circa 1825-1900) and Ellen Craft (1826-circa 1895), slaves from Macon, Georgia, escaped to Philadelphia and freedom. Ellen, who was light enough to pass as white, disguised herself as an ill planter travelling for treatment in the North while William played the role of servant. The architects of their own escape, they traveled boldly in public, by way of train and steamship. Once in Philadelphia, the Crafts became popular abolitionist speakers. In December 1848, William (circa 1825-1900) and Ellen Craft (1826-circa 1895), slaves from Macon, Georgia, escaped to Philadelphia and freedom. Ellen, who was light enough to pass as white, disguised herself as an ill planter travelling for treatment in the North while William played the role of servant. The architects of their own escape, they traveled boldly in public, by way of train and steamship. Once in Philadelphia, the Crafts became popular abolitionist speakers. |

|

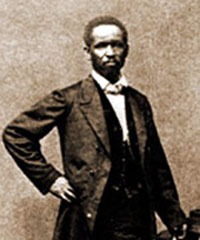

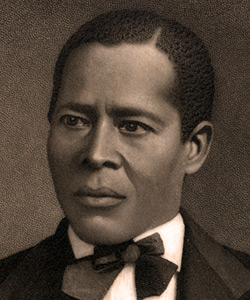

Martin Delany (1812-1885), was an accomplished and controversial man. Delany was a jack-of-all trades. He studied for a time at Harvard Medical School before he was expelled for being black. Thereafter, he became an advocate for voluntary colonization. His advocacy led him to write extensively and eventually try his hand as a newspaper editor. He participated in the Underground Railroad in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1865, Delany also became the first black officer commissioned in the Civil War. |

|

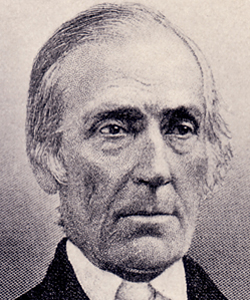

Thomas Garrett (1783-1871), a resident of Wilmington, Delaware, commenced his work helping fugitives in the 1820s. Garrett unabashedly gave life to his abolitionist ideals. He used his wife’s family fortune (she was from a banking family) to fund the freedom of more than fourteen hundred fugitives, whom he typically delivered into the hands of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. Garrett was a persistent, reliable resource for the Underground Railroad -- Harriet Tubman herself frequently appeared at his door for assistance. In 1848, Garrett was convicted of illegally assisting six slaves. He was fined fifteen hundred dollars. The setback was minor at best, however, and by the mid-1850s, he had redoubled his efforts. Thomas Garrett (1783-1871), a resident of Wilmington, Delaware, commenced his work helping fugitives in the 1820s. Garrett unabashedly gave life to his abolitionist ideals. He used his wife’s family fortune (she was from a banking family) to fund the freedom of more than fourteen hundred fugitives, whom he typically delivered into the hands of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. Garrett was a persistent, reliable resource for the Underground Railroad -- Harriet Tubman herself frequently appeared at his door for assistance. In 1848, Garrett was convicted of illegally assisting six slaves. He was fined fifteen hundred dollars. The setback was minor at best, however, and by the mid-1850s, he had redoubled his efforts. |

|

Daniel Gibbons was the brother-in-law of William Wright, the man credited with organizing the Underground Railroad in Lancaster County. Gibbons resided in close proximity to Wright, in the small town of Bird-in-Hand and this close proximity and the family connection made Gibbons’ home a convenient second stop in Wright’s burgeoning network. Wright received fugitives, and Gibbons distributed fugitives -- finding them homes nearby, or, if they were hotly pursued, passing them further along in the underground network. Gibbons frequently passed fugitives on to Jeremiah Moore, a resident of Christiana, Pa. Gibbons also famously assigned fugitive slaves their new, “freedom” names prior to allowing them to depart his home. Gibbons and Wright are a prime example of how entire families occasionally participated in the underground effort to aid escaped slaves. Daniel Gibbons was the brother-in-law of William Wright, the man credited with organizing the Underground Railroad in Lancaster County. Gibbons resided in close proximity to Wright, in the small town of Bird-in-Hand and this close proximity and the family connection made Gibbons’ home a convenient second stop in Wright’s burgeoning network. Wright received fugitives, and Gibbons distributed fugitives -- finding them homes nearby, or, if they were hotly pursued, passing them further along in the underground network. Gibbons frequently passed fugitives on to Jeremiah Moore, a resident of Christiana, Pa. Gibbons also famously assigned fugitive slaves their new, “freedom” names prior to allowing them to depart his home. Gibbons and Wright are a prime example of how entire families occasionally participated in the underground effort to aid escaped slaves. |

| William Goodridge was a free black who worked for the Underground in York, Pennsylvania. He was a successful merchant and businessman whose home was adjacent to a real railroad line in York City. Goodrich usually sent fugitives straight through to his contacts in Columbia, ensuring that notification that they were coming arrived in advance of their actual arrival. |

Laura Haviland (1808-1898), a Michigan native and Quaker, helped conduct many fugitives from Cincinnati to Michigan. On the pretense of picking berries, Haviland also ventured into Kentucky to extricate slaves. In 1838, she founded the Raisin Institute -- the school was both interracial and gender blind. During the Civil War, Havilland aided wounded soldiers. |

Born a slave in Lexington, Kentucky, Lewis Hayden (circa 1815-1889) was lifted from slavery by two abolitionists; he went on to extend the same assistance to countless other fugitives. Restless with slavery, Hayden and his family were assisted to freedom by abolitionist Calvin Fairbank and his associate Delia Webster; both Fairbank and Webster later served time in prison for their assistance. Hayden went on to found the Boston Vigilance Committee and simultaneously run a successful clothing business. Hayden’s three-story home provided immediate refuge for fugitives newly arrived in Boston. Hayden was instrumental in the rescue of Shadrach Minkins. Eventually brought to trial for his involvement in Minkins’ escape, Hayden was acquitted despite the fact that numerous witnesses had identified him as accompanying Minkins. Born a slave in Lexington, Kentucky, Lewis Hayden (circa 1815-1889) was lifted from slavery by two abolitionists; he went on to extend the same assistance to countless other fugitives. Restless with slavery, Hayden and his family were assisted to freedom by abolitionist Calvin Fairbank and his associate Delia Webster; both Fairbank and Webster later served time in prison for their assistance. Hayden went on to found the Boston Vigilance Committee and simultaneously run a successful clothing business. Hayden’s three-story home provided immediate refuge for fugitives newly arrived in Boston. Hayden was instrumental in the rescue of Shadrach Minkins. Eventually brought to trial for his involvement in Minkins’ escape, Hayden was acquitted despite the fact that numerous witnesses had identified him as accompanying Minkins. |

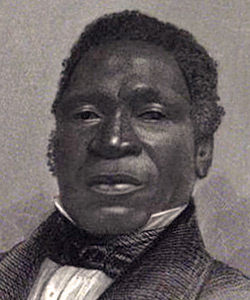

Josiah Henson (circa 1789-1883) was a Maryland slave whose remarkable metamorphosis from obedient slave to fiery abolitionist is one of the great stories of the Underground Railroad and abolitionist movement. Henson’s relationship with his master, Isaac Riley, was a unique one. Riley treated Henson well, and Henson performed his duties as a slave not only competently, but competitively. At the age of 18, Henson converted to Methodism. Eventually, Riley made Henson an overseer -- a reasonably unusual position for a black man to fill -- and even placed Henson at the head of an expedition to remove a sizeable number of his slaves to Kentucky, so that they would be beyond the reach of creditors. Henson lived happily in a managerial position in Kentucky until Riley’s creditors caught up with him and he ordered the slaves sold. Henson attempted to manumit himself and his family, but Riley cheated him by driving the manumission fee higher than Henson could ever hope to pay. Henson and his family fled, eventually crossing into Canada to be free. Later in life, Henson would return to Kentucky to assist fugitive slaves and eventually establish the Dawn colony in Canada. Henson hoped the colony would provide a permanent African American community residence that fostered work ethics and morals. What he got was a temporary community, which helped fugitive slaves transition from slavery to freedom. Josiah Henson (circa 1789-1883) was a Maryland slave whose remarkable metamorphosis from obedient slave to fiery abolitionist is one of the great stories of the Underground Railroad and abolitionist movement. Henson’s relationship with his master, Isaac Riley, was a unique one. Riley treated Henson well, and Henson performed his duties as a slave not only competently, but competitively. At the age of 18, Henson converted to Methodism. Eventually, Riley made Henson an overseer -- a reasonably unusual position for a black man to fill -- and even placed Henson at the head of an expedition to remove a sizeable number of his slaves to Kentucky, so that they would be beyond the reach of creditors. Henson lived happily in a managerial position in Kentucky until Riley’s creditors caught up with him and he ordered the slaves sold. Henson attempted to manumit himself and his family, but Riley cheated him by driving the manumission fee higher than Henson could ever hope to pay. Henson and his family fled, eventually crossing into Canada to be free. Later in life, Henson would return to Kentucky to assist fugitive slaves and eventually establish the Dawn colony in Canada. Henson hoped the colony would provide a permanent African American community residence that fostered work ethics and morals. What he got was a temporary community, which helped fugitive slaves transition from slavery to freedom. |

At the young age of 16, Isaac Tatum Hopper (1771-1852) moved from his New Jersey home to Philadelphia where he quickly evolved into a leading abolitionist. Hopper joined the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. He became famous for ferreting out loopholes in the fugitive laws, and delaying cases until slaveholders let them drop. |

Francis Julius LeMoyne (1798-1879) was a Washington County, Pennsylvania, doctor who opened his home to fugitives. He was a leading anti-slavery political figure in Pennsylvania and a founder of the state’s Liberty Party. A pillar of the community, LeMoyne also founded Washington Female Seminary, a free library and what is today, LeMoyne-Owen College, initially founded to educate blacks. |

Grace Ann Lewis (Graceanna Lewis) (1821-1912) opened her Chester County, Pennsylvania home to the Underground Railroad. She and her sisters were part of an abolitionist network that brought them into contact with the likes of William Still and Isaac Mendenhall (yet another Pennsylvania Underground Railroad stationmaster and abolitionist). She briefly harbored William Parker and his friend Abraham Johnson and Alexander Pinckney as they fled the backlash to the resistance in Christiana, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. |

|

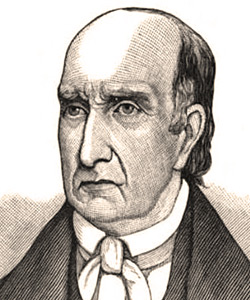

James Miller McKim (1810-1874) headed the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. McKim was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, graduated from Dickinson College, and became a Presbyterian minister before finding his life’s calling in the abolition movement in 1833. In spite of the unpopularity of abolitionism in Carlisle, McKim founded the Carlisle Anti-Slavery Society and, in 1840, McKim became the secretary to the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and editor of the Pennsylvania Freeman, the Society’s newsletter. McKim remained active even after the war. He founded the Philadelphia Port Royal Relief Committee, which provided assistance to local, newly freed blacks; in 1863, the organization went state-wide as the Pennsylvania Freedman’s Relief Association. But McKim’s work remained unfinished. McKim continued onward and, in 1869, served as the American Freedman’s Union Commission’s first secretary. McKim crowned his career as an abolitionist and then an advocate for free blacks by founding a New York paper, The Nation, which was a mouthpiece for the interests of newly emancipated blacks. James Miller McKim (1810-1874) headed the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. McKim was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, graduated from Dickinson College, and became a Presbyterian minister before finding his life’s calling in the abolition movement in 1833. In spite of the unpopularity of abolitionism in Carlisle, McKim founded the Carlisle Anti-Slavery Society and, in 1840, McKim became the secretary to the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and editor of the Pennsylvania Freeman, the Society’s newsletter. McKim remained active even after the war. He founded the Philadelphia Port Royal Relief Committee, which provided assistance to local, newly freed blacks; in 1863, the organization went state-wide as the Pennsylvania Freedman’s Relief Association. But McKim’s work remained unfinished. McKim continued onward and, in 1869, served as the American Freedman’s Union Commission’s first secretary. McKim crowned his career as an abolitionist and then an advocate for free blacks by founding a New York paper, The Nation, which was a mouthpiece for the interests of newly emancipated blacks. |

Shadrach Minkins (circa 1814-1875) was a fugitive black from Virginia who was arrested in Boston. Black abolitionist Lewis Hayden was at the center of the successful scheme to rescue Minkins, and spirit him away to freedom. A crowd of African Americans converged upon the courthouse where Minkins was being held, laid hold of Minkins, and carried him off. Minkins was handed over to Hayden who transported Minkins to Concord, where the fugitive was put on the path to Canada. Four days later, Shadrach, as he was known, became a new resident of Montreal and only months later, the proprietor of a new, Montreal restaurant. Shadrach Minkins (circa 1814-1875) was a fugitive black from Virginia who was arrested in Boston. Black abolitionist Lewis Hayden was at the center of the successful scheme to rescue Minkins, and spirit him away to freedom. A crowd of African Americans converged upon the courthouse where Minkins was being held, laid hold of Minkins, and carried him off. Minkins was handed over to Hayden who transported Minkins to Concord, where the fugitive was put on the path to Canada. Four days later, Shadrach, as he was known, became a new resident of Montreal and only months later, the proprietor of a new, Montreal restaurant. |

Solomon Northrup (1808-1863) was a fugitive slave who went on to write one of the most widely-recognized fugitive slave narratives of the time period. Interestingly enough, Northrup was born a freeman. The title of Northrup’s narrative largely indicates the plot of his story: “Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northrup, A Citizen of New York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, From A Cotton Plantation Near The Red River In Louisiana.” |

In 1837, Robert Purvis (1810-1898), a Southern-born, wealthy abolitionist of mixed race background, helped organize the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. There is some debate over whether it was Purvis, or James McCrummel, who served as the primary impetus behind the Committee’s organization and establishment, but it was Purvis who soon became the committee’s dominant figure. Purvis also founded a library for blacks, who were barred from Philadelphia’s numerous whites-only libraries. |

John Rankin (1793-1886) became the foundation of the Underground Railroad in Ripley, Ohio, but, like many abolitionists, was a minister first. And like other abolitionists before him, his first congregation recoiled from his anti-slavery doctrine and drove him off. Rankin and his large family then removed to Ripley where they lived comfortably as public abolitionists who enlisted several hundred Ohio residents to the resistance against slavery. |

By age 23, David Ruggles (1810-1849), a free black, was working for The Emancipator, an anti-slavery paper. He was traveling, selling subscriptions, and seizing the opportunity to lecture. Ruggles’ speeches were famously impassioned and a stirring experience for his audiences. Nevertheless, unmitigated loathing for the abolitionist cause and racism ruled New York, the state Ruggles called home. And so, the formation of the New York Vigilance Committee in 1835 was more a defensive maneuver than anything else. Ruggles served as the Committee’s first secretary. He led the Vigilance Committee to provide practical assistance, such as food and shelter, to fugitive slaves. Ruggles became a notoriously aggressive abolitionist who would force his way into the homes of New Yorkers to inform their slaves that they were free. Ruggles postulated that for blacks to be moral, they must also be educated. He did his part by first opening a bookshop, and when the bookshop was burned to the ground, a reading room. Interestingly enough, Ruggles did not believe in the mingling of the races. He advocated voluntary racial partition. Ruggles’ health first slowed, and then put a stop to Ruggles’ leadership efforts. By 1838, he was nearly blind, and, by 1839, the emotional toll of his work and his physical frailness drove Ruggles into retirement. By age 23, David Ruggles (1810-1849), a free black, was working for The Emancipator, an anti-slavery paper. He was traveling, selling subscriptions, and seizing the opportunity to lecture. Ruggles’ speeches were famously impassioned and a stirring experience for his audiences. Nevertheless, unmitigated loathing for the abolitionist cause and racism ruled New York, the state Ruggles called home. And so, the formation of the New York Vigilance Committee in 1835 was more a defensive maneuver than anything else. Ruggles served as the Committee’s first secretary. He led the Vigilance Committee to provide practical assistance, such as food and shelter, to fugitive slaves. Ruggles became a notoriously aggressive abolitionist who would force his way into the homes of New Yorkers to inform their slaves that they were free. Ruggles postulated that for blacks to be moral, they must also be educated. He did his part by first opening a bookshop, and when the bookshop was burned to the ground, a reading room. Interestingly enough, Ruggles did not believe in the mingling of the races. He advocated voluntary racial partition. Ruggles’ health first slowed, and then put a stop to Ruggles’ leadership efforts. By 1838, he was nearly blind, and, by 1839, the emotional toll of his work and his physical frailness drove Ruggles into retirement. |

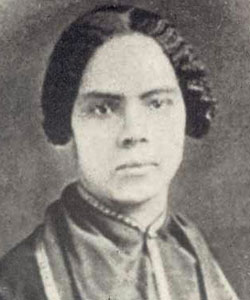

Mary Ann Shadd (1823-1893) grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Her father was a conductor in the Underground Railroad so she was exposed very early to abolitionist sentiment and resistance. Shadd began her career as a teacher, but found her calling as a journalist. In 1853, Shadd became the first black woman to run a North American newspaper when she launched the Provincial Freeman. Shadd used the newspaper to discuss how blacks would be free. She vehemently opposed segregation and turned her scathing critiques on exclusively black settlements and their proprietors. Eventually, public backlash against Shadd’s hotheaded-writing style and the fact that she was a woman forced her to allow her brother to supplant her as the publisher of the Provincial Freeman. During the Civil War, Shadd joined ranks with those such as Frederick Douglass and Jermain Loguen, enticing blacks to actively support the Union’s cause. Shadd lived to become the first woman to attend law school at Howard University. Mary Ann Shadd (1823-1893) grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Her father was a conductor in the Underground Railroad so she was exposed very early to abolitionist sentiment and resistance. Shadd began her career as a teacher, but found her calling as a journalist. In 1853, Shadd became the first black woman to run a North American newspaper when she launched the Provincial Freeman. Shadd used the newspaper to discuss how blacks would be free. She vehemently opposed segregation and turned her scathing critiques on exclusively black settlements and their proprietors. Eventually, public backlash against Shadd’s hotheaded-writing style and the fact that she was a woman forced her to allow her brother to supplant her as the publisher of the Provincial Freeman. During the Civil War, Shadd joined ranks with those such as Frederick Douglass and Jermain Loguen, enticing blacks to actively support the Union’s cause. Shadd lived to become the first woman to attend law school at Howard University. |

| Stephen Smith was a black lumber merchant in Columbia, Pennsylvania who assisted the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee in helping fugitive slaves escape. Smith and his cohort William Whipper owned a box car with a false end in which fugitives could hide safely even as the train carried them to freedom. Smith and Whipper also frequently employed their teamsters to drive fugitives, via turnpike, to freedom in Philadelphia or Pittsburgh. |

Peter Still (c. 1810-1868) was the brother of Underground Railroad legend William Still. Peter and William were separated as boys and were remarkably reunited when Peter arrived as freeman in the Pennsylvania Ant-Slavery office where Still worked as a clerk. In Peter’s recollection, he recalls that although he was in the hands of abolitionists, his freedom was so newly minted that he trusted no one. In anticipation of betrayal, he sat close to the door and tensed himself for a quick escape if anyone should try to send him back to slavery. |

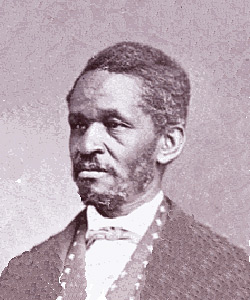

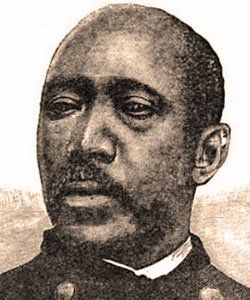

William Still (1821-1902) was a free black who went on to become the chairman of the Pennsylvania Vigilance Committee. Still was arguably the most important figure in the nation’s Underground Railroad coalition -- with a far-flung network of correspondents and participants. He began as a clerk in the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Office before taking over the vigilance operation in 1852. He kept meticulous records of slave names, freedman’s names, history of flight, etc. He later published his records as part of a memoir in 1872 that still stands as the most important documentary resource on the history of the Underground Railroad. During the Civil War, Still founded a coal supply company and helped provide supplies for black soldiers in the Union Army. The coal company remained successful after the war, and Still used his newfound status as a respected businessman to become a major community leader in Philadelphia. William Still (1821-1902) was a free black who went on to become the chairman of the Pennsylvania Vigilance Committee. Still was arguably the most important figure in the nation’s Underground Railroad coalition -- with a far-flung network of correspondents and participants. He began as a clerk in the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Office before taking over the vigilance operation in 1852. He kept meticulous records of slave names, freedman’s names, history of flight, etc. He later published his records as part of a memoir in 1872 that still stands as the most important documentary resource on the history of the Underground Railroad. During the Civil War, Still founded a coal supply company and helped provide supplies for black soldiers in the Union Army. The coal company remained successful after the war, and Still used his newfound status as a respected businessman to become a major community leader in Philadelphia. |

Harriet Tubman, born into slavery on the eastern shore of Maryland as Araminta “Minty” Ross, is perhaps the most famous individual hero of the Underground Railroad. She was toughened by slavery from an early age, suffering from a blow to her head by a slavemaster which caused her to suffer from seizures the rest of her life. Tubman had escaped to Pennsylvania in 1849, but she returned in 1850 to help some of her relatives who were up for auction. Harriet also returned to Maryland in 1851 to bring her husband, John Tubman, to Pennsylvania only to find he had taken another wife and did not to wish to return with her. This incident perhaps toughened Tubman as nothing else; rather than grieve the loss, she instead dedicated herself to helping others escape. She never remarried. John Brown referred to her as "General Tubman." She also worked closely with figures such as Thomas Garrett of Delaware and William Still of Philadelphia. Harriet Tubman, born into slavery on the eastern shore of Maryland as Araminta “Minty” Ross, is perhaps the most famous individual hero of the Underground Railroad. She was toughened by slavery from an early age, suffering from a blow to her head by a slavemaster which caused her to suffer from seizures the rest of her life. Tubman had escaped to Pennsylvania in 1849, but she returned in 1850 to help some of her relatives who were up for auction. Harriet also returned to Maryland in 1851 to bring her husband, John Tubman, to Pennsylvania only to find he had taken another wife and did not to wish to return with her. This incident perhaps toughened Tubman as nothing else; rather than grieve the loss, she instead dedicated herself to helping others escape. She never remarried. John Brown referred to her as "General Tubman." She also worked closely with figures such as Thomas Garrett of Delaware and William Still of Philadelphia. |

|

William Wright was a Pennsylvania Quaker who is considered the impetus behind the organization of the Underground Railroad in Lancaster County. His home in Lancaster County, Columbia served as a temporary sanctuary for freed and fugitive slaves. |

Moncure Conway (1832-1907) was born in Virginia, but received his education in the North at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania where he honed his talent as a writer. Although born in the South, Conway eventually became an abolitionist. Conway graduated from Harvard’s Divinity School and shortly thereafter, removed from Washington to Ohio. The Civil War commenced and Conway, considered one of the leading abolitionists of the day, was sent to Great Britain to plead the cause of the Union. Conway lived out the remainder of his life in England and then Europe, writing prolifically, and eventually his writings endeared him once more to the United States. He returned home to allow his wife to die and died himself soon after, alone, in Paris.

Moncure Conway (1832-1907) was born in Virginia, but received his education in the North at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania where he honed his talent as a writer. Although born in the South, Conway eventually became an abolitionist. Conway graduated from Harvard’s Divinity School and shortly thereafter, removed from Washington to Ohio. The Civil War commenced and Conway, considered one of the leading abolitionists of the day, was sent to Great Britain to plead the cause of the Union. Conway lived out the remainder of his life in England and then Europe, writing prolifically, and eventually his writings endeared him once more to the United States. He returned home to allow his wife to die and died himself soon after, alone, in Paris.

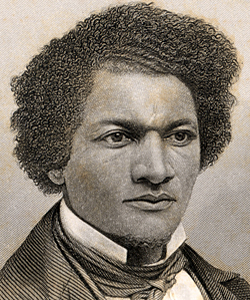

Frederick Douglass (1817-1895), once called Frederick Bailey, a slave in Maryland, escaped north and the most famous African American figure of his day. Bailey escaped using borrowed freedman’s papers, arriving in New York via a train that passed through Wilmington Delaware and Philadelphia. He was assisted by David Ruggles of the New York Vigilance Committee. Ruggles also helped bring Bailey’s wife, Anna Murray, from Maryland. Bailey selected Frederick Johnson as his freedman’s name; but when he settled in New Bedford, Rhode Island he soon changed it to Frederick Douglass when he discovered that Johnson was all too common of a last name. It was William Lloyd Garrison’s groundbreaking paper, The Liberator, which incited Douglass to enter the abolitionist movement. In 1843, Douglass was recruited for the New England Anti-Slavery Society’s sequence of conventions. The circuit made Douglass famous but it was also dangerous -- Douglass was attacked and grievously injured at least once. In addition, when he was home, Douglass served as a conductor for the Underground Railroad. Douglass then founded his own abolitionist paper, The North Star, for which he wrote diligently. After the war, he served first as a federal marshal in Washington D.C. under President Hayes, and then as the ambassador to Haiti.

Frederick Douglass (1817-1895), once called Frederick Bailey, a slave in Maryland, escaped north and the most famous African American figure of his day. Bailey escaped using borrowed freedman’s papers, arriving in New York via a train that passed through Wilmington Delaware and Philadelphia. He was assisted by David Ruggles of the New York Vigilance Committee. Ruggles also helped bring Bailey’s wife, Anna Murray, from Maryland. Bailey selected Frederick Johnson as his freedman’s name; but when he settled in New Bedford, Rhode Island he soon changed it to Frederick Douglass when he discovered that Johnson was all too common of a last name. It was William Lloyd Garrison’s groundbreaking paper, The Liberator, which incited Douglass to enter the abolitionist movement. In 1843, Douglass was recruited for the New England Anti-Slavery Society’s sequence of conventions. The circuit made Douglass famous but it was also dangerous -- Douglass was attacked and grievously injured at least once. In addition, when he was home, Douglass served as a conductor for the Underground Railroad. Douglass then founded his own abolitionist paper, The North Star, for which he wrote diligently. After the war, he served first as a federal marshal in Washington D.C. under President Hayes, and then as the ambassador to Haiti. William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), a native of Boston, was the founder of The Liberator, the leading and most radical anti-slavery newspaper in America from 1831-1865 which did a great deal to reshape the anti-slavery movement and made Garrison the nation’s leading public emancipationist. The establishment of The Liberator in 1831 was a turning point for the movement. Following the paper’s foundation, the abolitionist movement gained an uncompromising edge as well as a sense of immediacy the movement had not yet seen. Despite this urgency, however, Garrison was also known for his commitment to nonviolent resistance. In 1832 he founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society and in 1833 he organized and led the nation’s first national abolitionist conference in Philadelphia which led to the formation of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The Philadelphia conference published the famous “Declaration of Sentiments,” a document written in one night by Garrison himself which solidified the core values of the movement for the remaining years leading up to the Civil War.

William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), a native of Boston, was the founder of The Liberator, the leading and most radical anti-slavery newspaper in America from 1831-1865 which did a great deal to reshape the anti-slavery movement and made Garrison the nation’s leading public emancipationist. The establishment of The Liberator in 1831 was a turning point for the movement. Following the paper’s foundation, the abolitionist movement gained an uncompromising edge as well as a sense of immediacy the movement had not yet seen. Despite this urgency, however, Garrison was also known for his commitment to nonviolent resistance. In 1832 he founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society and in 1833 he organized and led the nation’s first national abolitionist conference in Philadelphia which led to the formation of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The Philadelphia conference published the famous “Declaration of Sentiments,” a document written in one night by Garrison himself which solidified the core values of the movement for the remaining years leading up to the Civil War.

In 1834, Jermain Loguen (circa 1813-1868), a Tennessee slave (otherwise known as Jarm Logue), boldly rode out of Tennessee and slavery, and continued to ride until he reached Canada and freedom. He adopted a freeman’s name, and went on to fund his own education at Oneida Institute. Loguen ultimately surfaced as one of the most impassioned antislavery preachers and visible underground agents of the day. Loguen worked as an underground agent in Syracuse, New York, where he defiantly handed out business cards, upon which was emblazoned “Underground Railroad Agent.” Loguen and his wife received fugitives ceaselessly, at all hours of the night and day, and even while their daughter lay fatally ill. Understanding that the qualifications for successful autonomy were education and vocation, Loguen agitated for jobs for blacks. With the end of the Civil War, Loguen remobilized and traveled, establishing a school and a church wherever he could for emancipated slaves.

In 1834, Jermain Loguen (circa 1813-1868), a Tennessee slave (otherwise known as Jarm Logue), boldly rode out of Tennessee and slavery, and continued to ride until he reached Canada and freedom. He adopted a freeman’s name, and went on to fund his own education at Oneida Institute. Loguen ultimately surfaced as one of the most impassioned antislavery preachers and visible underground agents of the day. Loguen worked as an underground agent in Syracuse, New York, where he defiantly handed out business cards, upon which was emblazoned “Underground Railroad Agent.” Loguen and his wife received fugitives ceaselessly, at all hours of the night and day, and even while their daughter lay fatally ill. Understanding that the qualifications for successful autonomy were education and vocation, Loguen agitated for jobs for blacks. With the end of the Civil War, Loguen remobilized and traveled, establishing a school and a church wherever he could for emancipated slaves.