Service for Freedom

Excerpt from “Men of Color, To Arms” (1863), read by Etsub Taye

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring freedom to all enslaved people in the Confederate states. This edict, however, did not free all Black people. The proclamation did not stipulate the freedom of Black slaves in the border states. Despite this knowledge in his speech “Men of Color, To Arms” Fredrick Douglass implored Black Men, specifically those in the northern states, to aid the Union by enlisting. Within his message, Douglass used rhetorical language and direct appeals to Black men in the North to put their liberty on hold for the freedom of their brethren. Douglass channeled his own agency to encourage the agency of Black men with the hope of achieving freedom however difficult the burden.

Douglass used rhetorical language in his speech to highlight that Black men were uniquely qualified to fight. More specifically, Douglass put “the arm of the slave” in juxtaposition with “the arm of the slaveholder.” By using the same language to describe both the slave and the slaveholder, he equalized them. Furthermore, Douglass assigned a double meaning to the word “arm” to mean gun. Black men had in their arsenal a metaphorical gun. Douglass then appealed to the pathos of his audience so that they might finally rise up and defeat their oppressors. He urges his audience to “unchain” their “powerful black hands” as if to remind them of their strength and the weapon they possess. He asks them to use their hands to fire that gun for freedom.

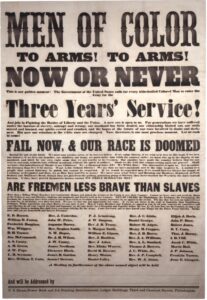

War poster aimed at Black men endorsed by Fredrick Douglass. Retrieved from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Douglass wrote “Men of Color, To Arms” mostly in the first person to relate to his audience. However, Douglass does briefly switch to second person in his fourth and fifth paragraphs. He employs the use of “you” and “your” to directly speak to his audience. By changing the perspective Douglass targeted his audience personally. He then placed his audience in opposition with the Black men, like Thomas Morris Chester, who were hesitant to join the Union army. Douglass appealed to his audience’s honor by labeling them as “brave” and those in opposition as “cowards.” Douglass turned the concerns of those men into insults and aimed them at his audience in order to evoke anger. But the underlying message of his speech is that he urged Black men to challenge the stereotype that they could not fight. That they were passive. By doing so he relays the message that if Black men join the Union Army their countrymen will recognize their efforts and award them freedom and equality.

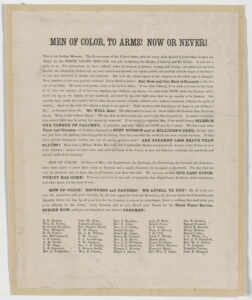

War recruitment poster aimed at Black men and appealing to the sense of honor. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Douglass successfully mobilized Black men into joining the Union Army. By the end of the war, Black men made up ten percent of the Union forces. But despite Douglass’s optimism, Black soldiers were relegated to menial tasks. They were disproportionately paid less than their white counterparts, were discriminated against and hated. Critiques of the 21st century might raise the question: was enlisting worth it? When analyzing what came immediately after the significance of their effort might not be recognized. Especially when examining how soldiers were treated after the war. However, Douglass’s speech and the presence of Black men in the army had far-reaching implications. Their presence in the army led to the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments as well as the Reconstruction era. By bearing the burden, Fredrick Douglass and the Black soldiers ensured freedom for all Black people.