The Abolition of Slavery through the Joint Efforts of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln

By Etsub Taye

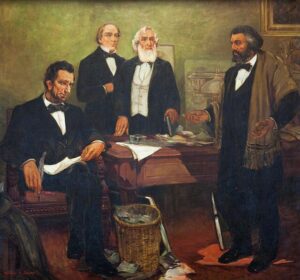

“Frederick Douglass appealing to President Lincoln and his cabinet to enlist Negroes” mural by William Edouard Scott. Courtesy of Washington DC’s Recorder of Deed of the Library of Congress

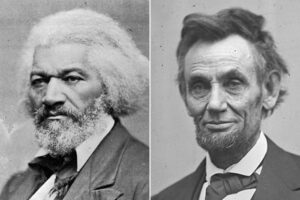

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude…shall exist in the United States.”[1] This simple phrase was the product of decades-long protests by antislavery and abolitionist movements in the United States. At the forefront of these movements, two figures: Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln stood guiding the nation on how to best attain freedom.

These two figures were almost never in agreement. Both Douglass and Lincoln had individual strategies which they implemented. Douglass was an outspoken reformer who used his oration to relentlessly confront and denounce slavery. Meanwhile Lincoln under the guise of moderation laid foundations for powerful coalitions. However, it was through their simultaneous efforts that the abolition of slavery was made possible.

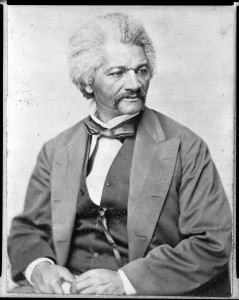

Douglass’s Pursuit of Freedom

Frederick Douglass was born a slave on a plantation in Maryland. According to the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass he experienced insurmountable hardship. [2] His early life was harsh and unforgiving as he was separated from his mother, beaten, starved, and overworked. Despite his slave owner’s attempts at breaking Douglass, he was determined to attain freedom. At the young age of eight, Douglass understood the connection between literacy and liberty. On the subject, he claimed, “once you learn to read, you will be forever free.”[3] So he bought the book The Columbian Orator and learned to read. This gave him an added agency which he tried using to attain freedom. When it didn’t work he fled and gained his freedom by utilizing the hired-out system during which he met with people and memorized routes. Douglass used the techniques he developed as a slave when he fought for the abolition of slavery.

For Douglass attaining his freedom was not enough. He had to use his agency to promote the agency of other enslaved people. In his 1852 speech “Fifth of July” Douglass argued, “for it is not light that is needed, but fire.”[4] He was directing his message to his fellow Garrisonions whom he was quickly becoming disillusioned. The Garrisionions used moral persuasion to denounce slavery which had appealed to a younger Douglass. But as the political climate of the decade changed it was no longer enough. This was especially true because slavery was expanding with the ratification of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Consequently, Douglass’s speech called for more radical action.

His disillusionment with the Garrisonians was not unique. Douglass would later curry favor with many antislavery movements and apply what he learned from his fugitive days by cultivating a network of coalitions along the way. He wanted to align with a movement that had enough political power to cause change. But to do so he would have to have “political appeal.”[5] Oakes asserts that as a result, Douglass’s antislavery stance becomes more moderate while simultaneously maintaining his core ideology: slavery had to be abolished. It is important to highlight Douglass became more moderate for the sake of pragmatism. His end goal was the end of slavery and he would take any road to achieve it.

Douglass was a gifted orator who used his skill with rhetoric for the freedom of the enslaved. In his newspaper Douglass Monthly he criticized the government, even during the Civil War. In September 1861 he called on the Government to “cast off the millstone” in response to them putting down a slaveholding rebellion. [6] His ability to write allowed him to reach hundreds of thousands of readers. This allowed him to wield public sentiment towards abolition. In doing so he shifted the center to be more radical.

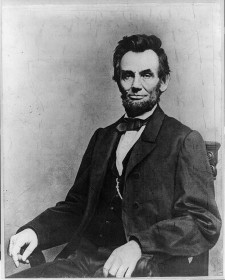

Lincoln’s Pursuit of Freedom

Abraham Lincoln was born in Kentucky to an impoverished white family. He grew up in Indiana where he had a year’s worth of schooling. The rest of his knowledge he acquired through sheer will. Lincoln was a self-taught scholar who, like Douglass, had an affinity for reading. While running for president Lincoln said his family’s move from Kentucky to Indiana was “partly on account of slavery.”[7] According to Oakes, this recollection is significant because Lincoln “could not recall a time when he did not hate slavery.”[8] However other scholars might have disagreed with Oakes citing confirmation bias.

In private Lincoln opposed slavery. Evidence of his dislike can be traced back to his correspondence with Joshua Speed in 1855. Lincoln wrote on the subject of runaway slaves :“I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught. . .but I bite my lip and keep quiet.”[9] Yet he did not advertise his hatred as anything more than concern for the nation. At the Republican State Convention Lincoln argued that “a house divided against itself cannot stand” when referring to the half slave half free proposition endorsed by Stephan A. Douglass.[10] His reasoning did not convey that he had any moral qualms with slavery. It only revealed his devotion to the nation which he believed would be harmed. But perhaps that was a part of his political acumen. Since he did not divulge too much of his ideology, voters couldn’t fault him for being anything other than a moderate Republican. He continued with this judgment in 1863. In Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, he did not explicitly refer to slavery. However, he declared that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.”[11] This commitment to the nation extended to the formerly enslaved because he placed an emphasis on a new beginning. Slowly with the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865 and plans set in motion for reconstruction, Lincoln was able to cause major political change using the foundations he had previously set.

Douglass and Lincoln’s Relationship

The relationship between Douglass and Lincoln ebbed and flowed. However, both figures recognized the genius of the other. They also respected one another. For instance, in 1864 Lincoln invited Douglass to the White House for the second time. During their meeting, Lincoln asked Douglass whether he should further explain to the public that he had been declining peace terms that didn’t include the emancipation of the enslaved. Lincoln told Douglass that he feared he was not going to get reelected if it appeared he was refusing to negotiate. It’s probable that Lincoln was doing this to scare Douglass and stop him from vacillating with his support. Douglass had a significant influence on hundreds of thousands of abolitionists. With the pressure from the war and his advisors perhaps Lincoln needed his support. But the exchange also spoke volumes to the trust Lincoln had for Douglass and how he recognized him as an equal. On his meetings with Lincoln, Douglass spoke well of him saying “Lincoln had received him just as you have seen one gentleman receive another.”[12] After the death of Lincoln, Douglass reminded his audience at the dedication of the emancipation memorial in 1876 that “Lincoln was preeminently the white man’s President.”[13] Yet he continued on by saying that Lincoln had to be in order for the war to end with the abolition of slavery.

Citations:

- U.S. Const. amend. XIII. (Passed by Congress on January 31, 1865. Ratified December 6, 1865)

- Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1849)

- Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass an American Slave.

- Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (July 5, 1852, Rochester, New York)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W Norton & Company)

- Frederick Douglass, “Cast off the Mill-Stone,” (Douglass’ Monthly, September 1861. University of Rochester)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics.

- Oakes.

- Abraham Lincoln to Owen Lovejoy, August 11, 1855; to George Robertson, August 15, 1855; to Joshua F. Speed, August 24, 1855; Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953)

- Abraham Lincoln, “House Divided Speech” (Republican State Convention, June 16, 1858)

- Abraham Lincoln, “Address at the Dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery” (Gettysburg, PA, November 19, 1863)

- Oakes, 229-32.

- Fredrick Douglass, “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln” (Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., April 14, 1876)