General Robert E. Lee looking out on to Pickett’s charge. Courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park. Photographed by Etsub Taye.

General Meade looking out into the battlefield facing General Robert E. Lee. Courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park. Photographed by Etsub Taye.

Fields in every shade of green as far as the eye can see lined the horizon of The Gettysburg National Military Park Museum. As I walked through the park it was as if I was walking through a mid-19th century American landscape painting. That is if it were not for the canons and wooden barricades that transported me 158 years back to the Battle of Gettysburg.

I had studied the Battle of Gettysburg in 8th grade but the details were fuzzy. However, walking through the Park Museum I was able to contextualize major scenes of the battle and the hardships the troops experienced. The monuments and statues littering the park allowed me to apply what I learned in the classroom and reconstruct it. For instance, on the second day of the battle, the Confederates carried out an assault on the Union Army who were positioned in the southern hills of Gettysburg. To reach Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, and Cemetery Ridge the Confederates had to travel uphill as Union troops fired from the top. I had only walked up a portion of hills but I thought it was extremely difficult. This gave me a newfound appreciation for the troops especially since they did it on foot while carrying about 50-pound backpacks. Within the context of the Museum, I found the monuments depicting the Confederate troops justified. Especially because the inclusion of both Union and Confederate troops allowed me to understand how the battle was waged.

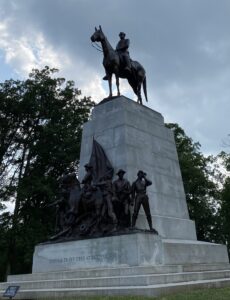

However, the depiction of a particular statue of a Confederate General did leave me with conflicting emotions. When I gazed upright onto a bronze figure atop his horse facing onwards to Pickett’s charge I immediately recognized the figure. It was Robert E. Lee. He and his horse were 14 feet high on top of a 27-foot pedestal. The pedestal included a couple figures who represented the variety of southern men who enlisted in the war. Within the context of the park, the General’s statue made sense. He was a significant figure who led the Confederate army throughout the entirety of the war. Lee was inarguably a great and strategic general.

Nevertheless, this monument which was donated by the State of Virginia is the largest monument of any general, even that of General George G. Meade whose monument spans 23.5 feet in total. To make matters worse the statue was erected in 1917 during Jim Crow Laws on Federal Land. I interpreted the large scale of Lee’s statue as an implication that we should celebrate him. By forcing onlookers to look up at him the statue implicitly suggested that we the audience should exalt him–a man who betrayed the Union. And if he was successful would have allowed a nation to continue the enslavement of an entire race–my race.

Although I didn’t think the statue should be removed, I objected to the way he was memorialized. I wasn’t shocked by his presence but it did raise a question: why is our nation so adamant about memorializing historical figures with racist and traitorous legacies on public land? My only consolation was that miles away on Cemetery Ridge General George G. Meade gazed back at Lee with authority and certainty of what would come.