DATELINE: DECEMBER 23, 1848, MAYSVILLE, KY

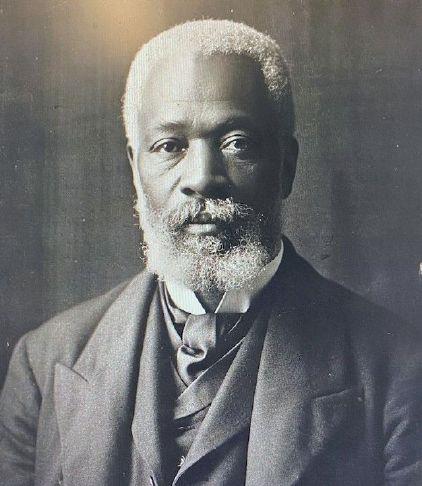

Kentucky freedom seeker Peter Pointz (Clyde Advertiser-Tribune)

Enslaved Kentuckian Peter Pointz could tell that local slaveholders were on edge. As a porter at the Goddard House, one of the most popular hotels along Maysville’s bustling riverfront, Pointz had plenty of opportunities to eavesdrop on the conversations of enslavers while he lugged their heavy trunks from arriving steamboats back to the hotel, or during his rounds tending to guests’ rooms. Pointz would later recall “the fall of 1848” as a “critical” time when “many slaves were escaping to Canada by way of the underground railroad.” Panicked slaveholders redoubled their vigilance. “The blacks were watched very closely,” Pointz remembered. However, the tightening vise did not dissuade Pointz’s efforts to realize his freedom—after all, he knew that a sophisticated Underground Railroad network of Black and white activists existed on both sides of the Ohio River at Maysville and Ripley. Two days before Christmas 1848, Pointz and his girlfriend, the hotel’s enslaved chambermaid, Mary Gross, used that network to cross the Ohio River and realize their freedom. [1]

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

In April 1847, a Cincinnati newspaper reported on a “Grand Stampede” from Kenton County, Kentucky, the first known use of the term “stampede” to describe a group escape from enslavement. Within weeks, in May 1847, newspapers in the nearby riverside town of Maysville, Kentucky were using the term to report “Another Stampede” of freedom seekers from their vicinity. [2] During the fall and winter of 1848, Maysville papers regularly invoked the term “stampede” to describe what they saw as a disturbing trend of group escapes. [3]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Although Maysville newspapers worried about the apparent uptick in group escapes during the late 1840s, flight from enslavement was nothing new. For decades, enslaved Kentuckians escaping from Maysville had enlisted the help of an extensive network of Black and white activists across the river in Ripley, Ohio. Ripley’s reputation as a hotbed for abolitionism owed to several factors, including the two sizable free Black communities situated a short distance outside town, which traced their roots back to 1818, when British merchant Samuel Gist’s will emancipated 950 people enslaved on his Virginia plantation. Unable to stay put due to the Virginia legislature’s hostility towards free Blacks, the 950 men, women, and children picked up and relocated north of the Ohio River, staking out two large settlements outside Ripley in Brown County, Ohio. [4]

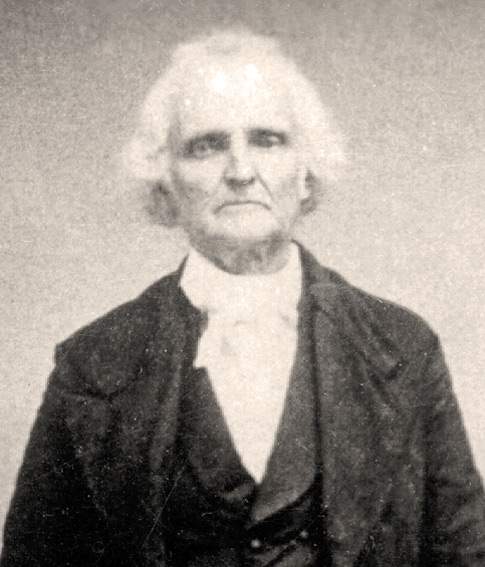

An active and outspoken community of white abolitionists also called Ripley home, spearheaded by Presbyterian minister John Rankin and his family of stalwart abolitionists. In 1829, Rankin purchased a house on top of a steep hill overlooking Ripley and the Ohio River. From their new hilltop home, the Rankins sheltered countless freedom seekers. “I kept a depot on the Underground Railway, at which many passengers entered for Canada, as many as twelve at a time on some occasions,” Rankin later recalled. “Whole families, parents and children, were sheltered under my roof on their way to Canada.” [5]

Rankin House, Ripley, Ohio (Wikipedia)

Underground Railroad activist John Rankin (House Divided Project)

Rankin’s home was but the first stop on an extensive Underground Railroad network spanning northward from Ripley. Rankin’s sons, John Rankin, Jr., Adam Lowry Rankin, and Richard Calvin Rankin, regularly guided freedom seekers from their father’s home above Ripley some six miles north to Redoak, where the Gilliland and Hopkins families were prepared to help enslaved runaways. From there, the next stop was frequently another fifteen miles north at Sardinia, where enslaved people could expect assistance from Dr. Isaac Beck and his large family, Methodist minister John B. Mahan, and free Black activist John D. Hudson. [6]

As slaveholders feared, the Underground Railroad network also reached into Kentucky; white and Black activists routinely crossed the Ohio River to guide freedom seekers to Ripley. White abolitionist and schoolteacher Calvin Fairbank shepherded enslaved people across the Ohio River at Ripley during the early 1840s, before he was caught during one such trip elsewhere in Kentucky, convicted of slave-stealing, and sentenced to the Kentucky state penitentiary in 1844. [7] Kentucky freedom seeker Josiah Henson, who had escaped the Bluegrass State and resettled in Canada in 1830, risked more than prison time when he made a daring trip back to the Maysville area from Canada to lead other freedom seekers to safety. [8] So too did John P. Parker, a formerly enslaved man who bought his freedom and relocated to Ripley in 1849. Parker made numerous trips to Kentucky soil to guide freedom seekers across the river. Parker’s exploits were so well known that exasperated Kentucky slaveholders unsuccessfully tried to kidnap him in October 1852. [9] Peter Pointz, who escaped from Maysville in a December 1848 “stampede,” later returned to Kentucky to rescue his nephew from bondage in Louisville. [10]

A series of stampedes beginning during the late 1840s confirmed slaveholders’ worst fears about the Underground Railroad network between Maysville and Ripley. On the heels of two “stampedes” from nearby Kenton and Boone counties, in which as many as 33 men, women, and children successfully escaped, the Maysville Eagle reported “Another Stampede” of 10 enslaved people from their town in May 1847. The paper did not identify the 10 freedom seekers, except to say that they belonged to four different enslavers in Maysville and that the freedom seekers ran away Sunday night, May 16, following church services. [11]

Already suspicious of outsiders, a newspaper in nearby Covington, Kentucky quickly pointed the finger at “a distinguished preacher” of the Northern Methodist Church, who was at the home of one of the Maysville slaveholders “at the time his negroes left.” As the paper’s readers would have known, differences over slavery had wrenched the Methodist Church into Northern and Southern factions three years earlier in 1844. The church’s national split was mirrored locally, where Maysville’s Methodists remained bitterly divided over slavery. At the time of the May 1847 stampede, the pro- and anti-slavery factions of Maysville Methodists were tussling over ownership of the church building and hosting rival preachers: an antislavery Dr. Joseph Tomlinson and a rival Southern Methodist preacher named Grubbs. [12] It is unclear whether the enslaved Kentuckians viewed the split within Maysville’s Methodist community as an opportunity to solicit assistance for their escape. However, the proslavery Covington, Kentucky Register made that insinuation, noting that “five or six” of the escapees “belonged to a prominent and influential member of the Northern Methodist Church at Maysville.” The Maysville slaveholder who was a member of the Northern Methodist Church had lost his human property, the paper warned, and others would too if they allowed preachers from the church’s Northern wing to speak from the pulpits. [13]

More than a year later in October 1848, several groups of enslaved Kentuckians escaped during the final weeks of the presidential campaign. According to the Maysville Flag, “four or five slaves have left their masters in this city and vicinity––a number have runaway from Montgomery––and Heaven only knows how many have fled from other parts of the State.” Enslavers managed to recapture three freedom seekers “in the vicinity of Ripley, before they succeeded in crossing the river,” but “several others are still missing.” The fate of the other freedom seekers remains unclear, though a report from a Cleveland newspaper suggests they may have successfully escaped. She Cleveland Plaindealer announced that “seven run away slaves passed through that city” on Monday night, November 13, reportedly “on their way to Canada.” The seven freedom seekers may well have come from Maysville through the Ripley Underground. [14]

Ohio senator Thomas Corwin (House Divided Project)

Amid the heightened atmosphere of the presidential election, the Maysville Flag, a pro-Democratic paper, seized on the latest rash of escapes to attack their political rivals, the Whig Party, on the issue of slavery. Shortly before the latest stampede, several prominent Kentucky Whigs, including former governors Robert P. Letcher and Thomas Metcalfe, had traveled to Ripley to stump for Whig nominee Zachary Taylor. The Flag, which favored Taylor’s Democratic rival, Lewis Cass, castigated Kentucky Whigs for “fraternizing with the Abolitionists of Ohio” — in particular Ohio senator Thomas Corwin, outspoken for his support of the Wilmot Proviso, which proposed to limit the expansion of slavery in western territories gained during the Mexican-American War. “Last week we warned our friends against another negro stampede, which we supposed would follow the holding of the Corwin meeting at Ripley,” the paper trumpeted. Blaming Corwin and the Whigs for mounting escapes offered a convenient political strategy for the pro-Democratic Flag, which hoped to paint their Whig rivals and presidential candidate Zachary Taylor as insufficiently proslavery for Kentucky voters. Even amid the partisan jostling, the Flag begrudgingly acknowledged that a sophisticated Underground Railroad network between Maysville and Ripley: “It appears that they [enslaved people] all aim to get to Ripley, in the hope, we suppose, of meeting their brother Tom [Corwin], or some other kindred, who will aid them in passing on the subterranean rail road north.” [15]

A month later, the Maysville Flag was still blaming Corwin and the Whig Party for the rising tide of escapes when it reported yet “Another negro Stampede” that occurred just before Christmas on Saturday night, December 23, 1848. A man and a woman escaped from the Goddard House hotel, and other enslaved people were suspected missing too. “It is supposed that several others have left the city and county.” The Flag believed that “the deluded creatures” escaped “under the impression that Tom. Corwin is yet speaking in their behalf at Ripley Ohio, and have crossed over to make the acquaintance of their ‘colored broder.’” Even though Corwin was already back in Washington for the opening of the new session of Congress, the Flag seethed that “he has left enough Abolitionists about Ripley to protect and run off these absconding slaves.” [16]

Goddard House (modern-day Lee House Inn) in Maysville, Kentucky (Wikipedia)

The man and woman who escaped from Goddard’s hotel were enslaved couple Peter Pointz and Mary Gross. For the past three years, Pointz’s slaveholder had hired him out (or rented him) to Mrs. Goddard at her popular Maysville hotel, the Goddard House (modern day Lee House Inn), situated along the riverfront at the corner of Front and Sutton streets, directly across from the steamboat landing. There, Pointz worked as “porter, bell boy and tending the men’s rooms.” His job as a porter provided him with plenty of opportunities to amass money and plan his escape. “The porters went to the river when the boats came in,” Pointz later recalled, “and often got tips for carrying trunks and carpet sacks.” Pointz “made quite a bit of money in this way” and by December 1848 had pocketed several hundred dollars. His position at the hotel also gave him the opportunity to court Mary Gross, the hotel’s enslaved chambermaid. The couple hoped to escape to freedom together with their savings. [17]

Sometime in mid-December, Pointz and Gross arranged to meet “a white man, agent of the underground railroad, [who] would be in town soon and would take any who wished to leave with him to Canada, and it would cost us nothing.” But the man never showed, and the enslaved couple “gave up the idea of going away until spring.” However, soon after Pointz learned that learned that Gross had “told of our plans.” Pointz feared that if word got back to his slaveholder, he would face sale to the Deep South. “This scared me so that I began at once to get my things in shape to leave.” Pointz gathered his cash and prepared to leave immediately. [18]

On Saturday night, December 23, 1848, Pointz, Gross, and another enslaved couple, Lewis Ford and his unidentified girlfriend, all went to Beesley’s Bottom “about a mile or so from town,” where they had arranged to meet with a free Black man named Shell, who lived in Ripley but worked in Maysville. The river was high and Shell did not come. According to Pointz, “Ford got frightened and took his girl back to the city,” where she returned to her enslaver’s home “without being missed or heard.” After waiting at Beesley’s Bottom until 2am, Pointz and Gross resolved to do the same. The couple headed back “to get things in shape at the hotel before we were missed.” On their way back to Maysville, they ran into Ford, who had found Shell and his brother and informed them “everything was ready for us to leave.” Without time to contact Ford’s girlfriend, the three freedom seekers crossed with Shell and his brother, who charged them $80 for his assistance. [19]

AFTERMATH

Weary and bedraggled, the three freedom seekers reached Ripley at 4 am on Christmas Eve. From Ripley, the three were “taken on horseback” (Pointz did not specify by whom) to a farm several miles outside town, where at dawn they reached the farm of the Delaneys, a family of free Blacks. On Sunday night, Christmas Eve 1848, they traveled on horseback to the farm of “a Mr. Voorhees,” where “other runaway slaves” were already taking refuge. The next evening, December 25, Vorhees “took seventeen of us to the next place,” Pointz remembered, “so on travling [sic] in the night on horses, we went from place to place” until they reached Delaware, Ohio, and then by foot to Mt. Gilead in central Ohio. In two weeks, Pointz, Gross, and Ford traveled more than 150 miles from Ripley to Mt. Gilead by horse and by foot. Pointz and Gross stayed in Mt. Gilead until May 1850, where they attended school for the first time, before continuing further north. [20]

FURTHER READING

Peter Pointz’s recollection of his escape from slavery, published posthumously in 1898, provides the best primary source account from an enslaved perspective of a “stampede” from Maysville during the late 1840s. [21]

Several scholars have explored the crucial Underground Railroad network between Maysville and Ripley, including Ann Hagedorn’s Beyond the River (2002) and Keith Griffler’s Front Line of Freedom (2004). [22] J. Blaine Hudson’s exhaustive study of Kentucky freedom seekers helps contextualize the growing trend of group escapes; Hudson’s database of fugitive slave advertisements from Kentucky points to 1850 as a clear “dividing line,” in which group escapes spiked (both numerically, and as a percentage of overall escapes during the period from 1850-1860). [33] As the alarmed reports from Maysville newspapers during the late 1840s suggest, the changing dynamics of slave flight were already becoming apparent to enslavers on the Kentucky borderlands.

[1] “The Death of Peter Pointz,” Clyde (OH) Enterprise, March 31, 1898

[2] “Another Stampede,” Maysville (KY) Eagle, May 18, 1847

[3] “Runaway Slaves!,” Maysville (KY) Flag, November 1, 1848; “Another negro Stampede,” Maysville (KY) Flag, December 25, 1848

[4] Ann Hagedorn, Beyond the River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002) 12-13.

[5] John Rankin, Life of Rev. John Rankin, Written by himself in his 80th year (1872, self-published, Arthur W. McGraw, 1998), 46, 49; Hagedorn, Beyond the River, 56-57.

[6] Hagedorn, Beyond the River, 82-89.

[7] Calvin Fairbank memoir, 1893, Wilbur H. Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection, see p. 6 [WEB]

[8] Josiah Henson, Truth Stranger than Fiction: Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1858), 145-153, [WEB].

[9] John P. Parker, Stuart Seely Sprague (ed.), His Promised Land: The Autobiography of John P. Parker, Former Slave and Conductor on the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 146-151.

[10] “The Death of Peter Pointz,” Clyde (OH) Enterprise, March 31, 1898

[11] Maysville (KY) Eagle, “Another Stampede,” May 18, 1847

[12] Randolph Paul Runyon, The Assault on Elisha Green: Race and Religion in a Kentucky Community (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2021), 22-25.

[13] “Negro Stampede,” Worcester (MA) Bay State Farmer, May 29, 1847; “Negro Stampede,” New Lisbon (OH) Anti-Slavery Bugle, June 18, 1847; “Negro Stampede,” Boston (MA) Liberator, July 16, 1847

[14] “Runaway Slaves!,” Maysville (KY) Flag, November 1, 1848; “A Stampede,” Detroit (MI) Free Press, November 21, 1848

[15] “That’s right–Give them ‘goss,” Maysville (KY) Campaign Flag, October 27, 1848; “Runaway Slaves!,” Maysville (KY) Flag, November 1, 1848

[16] “Another negro Stampede,” Maysville (KY) Flag, December 25, 1848

[17] “The Death of Peter Pointz,” Clyde (OH) Enterprise, March 31, 1898; Judith Goddard managed several hotels in Cincinnati and Maysville previously. A November 1846 advertisement announced that she had taken over management of the hotel on Front and Sutton streets, the modern-day Lee House. See National Registry of Historic Places, Nomination Form, 1977, [WEB].

[18] “The Death of Peter Pointz,” Clyde (OH) Enterprise, March 31, 1898

[19] “The Death of Peter Pointz,” Clyde (OH) Enterprise, March 31, 1898; Pointz did not identify Ford’s girlfriend by name, except to say that she “belonged to the cashier of the bank.”

[20] “The Death of Peter Pointz,” Clyde (OH) Enterprise, March 31, 1898

[21] “The Death of Peter Pointz,” Clyde (OH) Enterprise, March 31, 1898

[22] Hagedorn, Beyond the River; Keith Griffler, Front Line of Freedom: African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2004).

[33] J. Blaine Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 33.