This post is the first of two posts on the first newspaper-identified “slave stampede” in American history from Kentucky; see also 1847 Kenton and Boone County Stampedes: Part 2.

DATELINE: APRIL 24, 1847, KENTON COUNTY, KY

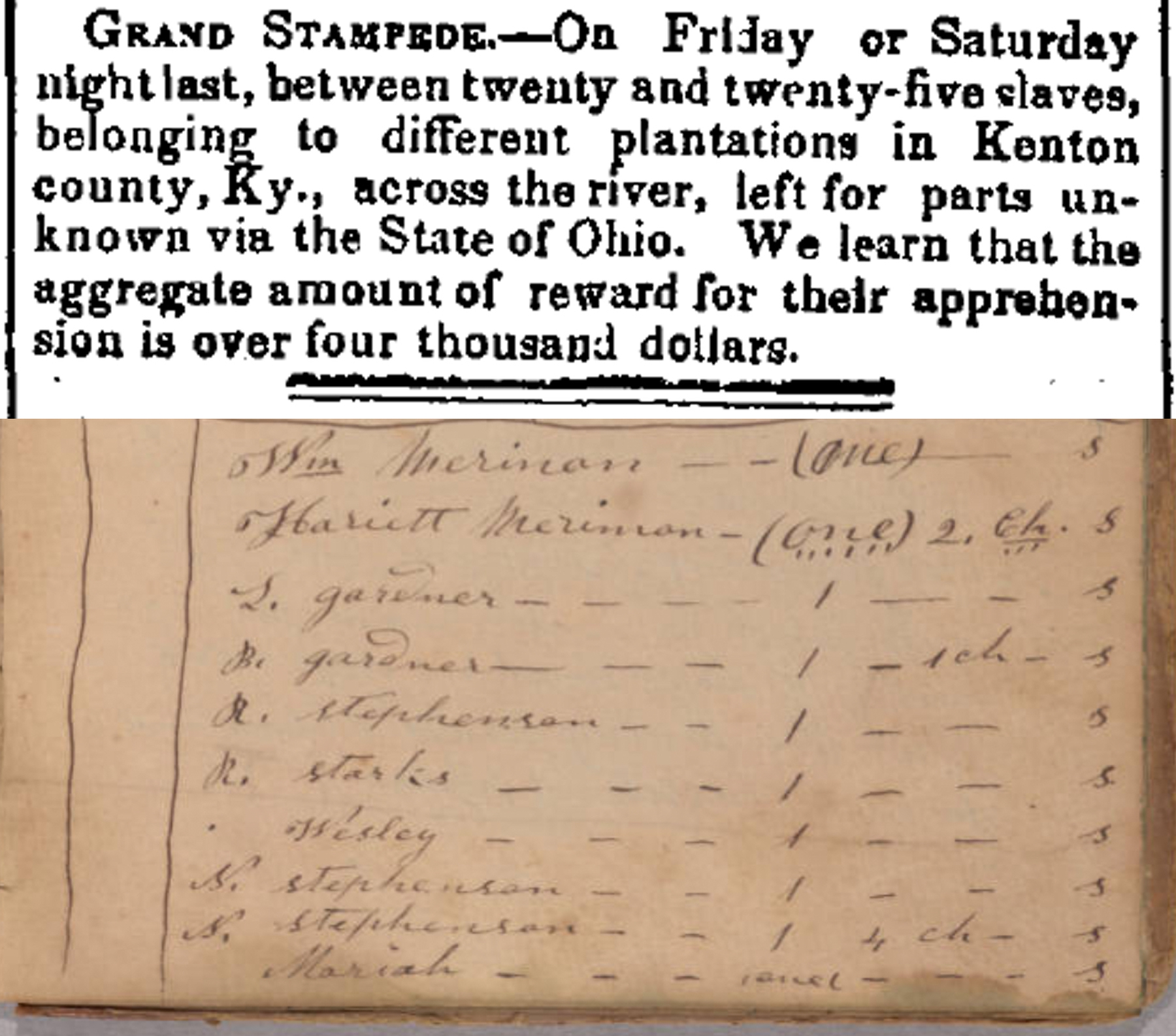

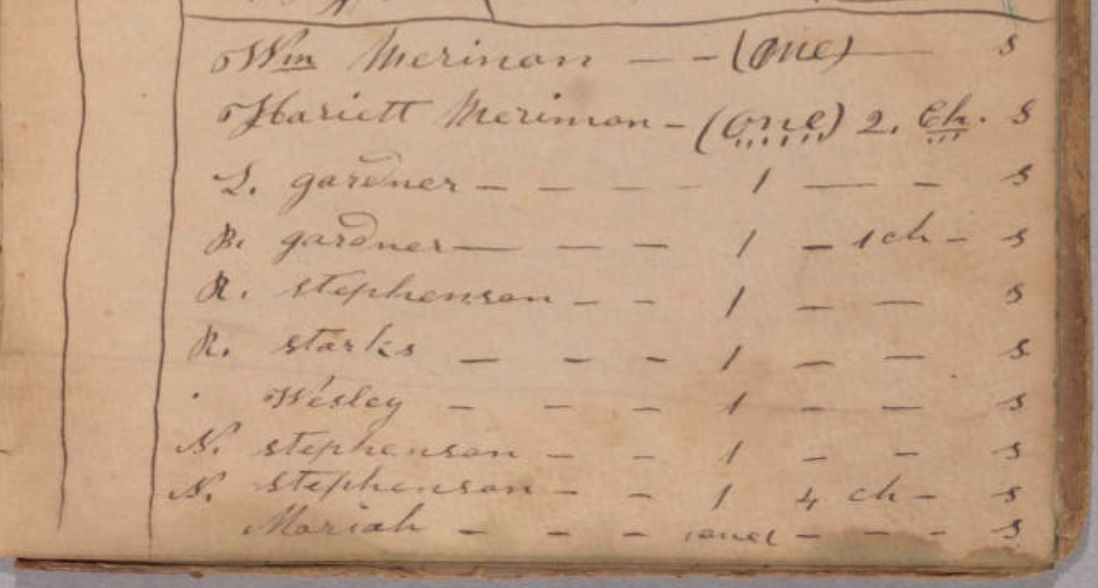

Above, the Cincinnati (OH) Commercial Tribune, April 28, 1847 coins the term “stampede” to refer to group escapes (Newspapers.com), while below, a detail from Zachariah Shugart’s account book lists the names of the Gardner (aka Casey) and Stevens families who escaped in the stampede (Huntington Library)

Sometime in May 1847, Michigan farmer Zachariah Shugart opened his account book and added several new names to a list of “Runaway Negroes” whom he had assisted over years of Underground Railroad activism. Shugart scrawled the names of Kentucky freedom seekers “L Gardner” “B Gardner” and their “1 ch[ild]”: Lewis and Betsy Gardner, and their young daughter Mary. Shugart also recorded five members of the “Stephenson” or Stevens family: Reuben, Nelson, Nancy, and likely at least two of her children, Peter and Anny. [1]

Shugart’s account book documented just part of two bold mass escapes from slavery during the spring of 1847. Multiple families–33 enslaved men, women, and children in all–liberated themselves from two northern Kentucky counties in under a month. In response, newspaper editors across the river in Cincinnati coined a new term to describe the growing trend of large, group escapes from slavery: the “slave stampede.” [2]

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

The April 1847 stampede marked the first known application of the term “stampede” to describe group escapes from enslavement. Within days of the first group escape on April 24, at least two Cincinnati newspapers reported it under the headline: “Grand Stampede.” [3] The term quickly captivated public attention. Newspapers across the country reprinted the headline “Grand Stampede” and its brief description of the large group escape. [4]

In 1847, the term “stampede” had only recently entered Americans’ vocabulary. Reports on the ongoing US-Mexican War (1846-1848) and expansion into the southwest introduced the term “stampede” to American readers; both to describe Mexican troops “stampeding” from the battlefield and droves of cattle “stampeding” across the western plains. It was no coincidence that the first reports of “slave stampedes” in 1847 ran alongside dispatches from the frontlines of the Mexican War. [5]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Six slaveholders jointly advertised a $3,125 reward for 18 of the 22 freedom seekers who escaped in the April 24 stampede (Amherstburg Freedom Museum)

Families from six different plantations joined the initial mass escape from Kenton County on Saturday, April 24. From slaveholder Thornton Timberlake’s plantation came the Hughbanks family: 45-year-old Jonathan, 33-year-old Nancy, 16-year-old Mary, and Robert (either 14 or 15 years old). Twenty-six year old Lewis (also known as William) and 22-year-old Betsy (also known as Elizabeth) Gardner escaped from different slaveholders, and brought their young daughter Mary too. Once free, the Gardner family adopted the surname Casey. Nancy Stevens (also written as Stephens and Stephenson) escaped from Thomas Lindsay’s plantation, taking two of her children, Peter who was seven or eight years old, and Anny who was three or four. The oldest freedom seeker was Rachel, in her late 60s, who escaped from slaveholder Alexander P. Sandford. Two days on April 26, the six affected slaveholders jointly advertised a $3,125 reward for the freedom seekers’ recapture. [6]

Within weeks, the 22 freedom seekers successfully reached Cass County, Michigan. Few specifics about their journey survive, but all signs suggest that the freedom seekers traveled a familiar Underground Railroad route (described below) that veered northwest through central Indiana all the way to southern Michigan. Within a few weeks, the freedom seekers had reached the end of that route, an abolitionist enclave in Cass County, Michigan. Several of the freedom seekers found work and boarding on the farm of Quaker abolitionist Zachariah Shugart, located about three miles outside Cassopolis. In his account book, Shugart recorded the arrival of “L. Gardner” and “B Gardner” (Lewis and Betsy Gardner/Casey), a man named “Wesley,” as well as the Stevens family (recorded as “Stephenson”). [7]

Michigan abolitionist Zachariah Shugart’s account book recorded the arrival of multiple freedom seekers from the April 24 stampede, including the Gardners/Casey family and the Stephenson/Stevens family. (Huntington Library)

Back in Boone County, Kentucky (next to Kenton County), enslaved man Perry Sanford knew many of the freedom seekers who had escaped in the April 24 stampede. But as Sanford later told a journalist, their successful escape was not what inspired him to head north; rather, it was his slaveholder’s panicked reaction that prompted a second group escape from Kenton County. “Their [April 24] escape alarmed the slave owners and they began to sell off their slaves to the Mississippi cotton planters,” Sanford recounted. Sanford’s enslaver, Milt Graves, was among the panic-stricken slaveholders. Several weeks after the initial stampede, Graves’s son, “a talkative youngster, told me that his father had sold us into Mississippi.” Decades later, Sanford still remembered the shock and dread he felt at hearing the news. “I was struck with dismay. The horror of all horrors to the slave was the Mississippi cotton field. It was a living hell.” [8]

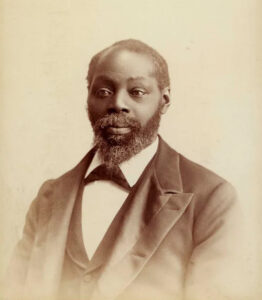

Freedom seeker Perry Sanford later in life (Battle Creek Enquirer)

Later that day while working in the field, Sanford quietly communicated “the startling information I had received to the other slaves.” When the overseer left for a few minutes, Sanford and other enslaved Kentuckians huddled together and “resolved on an escape.” Sanford tallied a total of 12 individuals planning to join the escape. Much like the first group of 22 freedom seekers, this second group consisted of men, women, and children: in addition to Perry Sanford, there was the Merriman family, William, Samuel, Isabella, and Hannah; James and Dorcas Oglesby; David (Dave) Walker and his mother, Susan Reynolds; and two other men, Abraham Washington and Tom Harris. One of the freedom seekers managed to secure a pass and traveled to Covington, where they made arrangements with an unidentified white man to help the group navigate the river-crossing to Cincinnati. [9]

Reaching Covington took longer than expected. Although the freedom seekers only had to cover 12 miles from their plantation to the riverside town of Covington, Sanford explained, “we had to travel across the fields in order to avoid meeting teams and travelers and to pass the tollgates.” The group did not reach Covington until 4 am. By then, the white man who had agreed to ferry them across the river had tired of waiting and gone home. “This was a great disappointment to us,” Sanford recalled, “but we started down the bank of the Ohio River and almost providentially found a boat, or as they are called there, a skiff.” Sanford and 10 others crowded into the skiff. “The sides came to within an inch of the water,” Sanford detailed. “How we ever got across I don’t know. But it was life or death, as we made the attempt and reached Cincinnati in safety.” All 11 freedom seekers who attempted the river crossing made it safely across––one man, Henry Buckner, was reportedly drunk and failed to arrive in time. Slaveholders punished Buckner for his attempt to flee enslavement, though he escaped less than two years later. [10]

In Cincinnati, Sanford and the 10 other freedom seekers linked up with the city’s Underground Railroad network. “As we landed, we saw a colored and a white man standing together. They exclaimed: ‘There comes some runaway slaves.’” The freedom seekers’ dread soon turned to relief; they had stumbled into Cincinnati’s network of Underground Railroad activists. The two Underground Railroad operatives divided the group into pairs, and “we were distributed around and secreted in the cellars of business blocks,” Sanford recalled. [11] The cadre of Underground Railroad operatives who sheltered Sanford’s group may well have included Quaker abolitionists Levi and Catharine Coffin, who had just relocated to Cincinnati weeks earlier in April 1847. [12]

After laying low for a week in Cincinnati, abolitionists guided Sanford and the other ten freedom seekers northward along a well-established Underground Railroad route that veered northwest through central Indiana all the way to southern Michigan. Leaving Cincinnati, the freedom seekers headed to Hamilton, Ohio, and then northwest to Jonesboro, Indiana. Near Jonesboro, the freedom seekers met up with Quaker abolitionist bothers George and John Shugart. “We only traveled nights, and in covered wagons,” Sanford detailed, “and would be secreted day times in some Quaker’s barn or in the woods.” Along the way, Quaker abolitionists provided the freedom seekers with new clothes. [13]

Sanford did not mention any other stops by name until they neared Cassopolis, Michigan, but his 1884 interview aligns closely with what Quaker abolitionists later told historian Wilbur Siebert about a well-traveled Underground Railroad route from Cincinnati to southern Michigan. Assuming Sanford’s group followed the familiar route, they likely continued north from Jonesboro to North Manchester, Indiana, where they may have sought refuge with abolitionist Morris Place. Then, they likely proceeded north to Goshen, Indiana, where a Dr. Matchett assisted freedom seekers. [14]

AFTERMATH

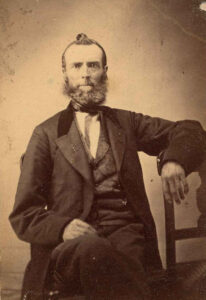

Abolitionist farmer Zachariah Shugart offered housing and work to freedom seekers from the two stampedes, including the Gardner (Casey) family. (Huntington Library)

After about a month of travel, the freedom seekers reached Young’s Prairie, about three miles outside Cassopolis, Michigan. There, abolitionists Stephen Bogue and Zachariah Shugart (brother of George and John Shugart in Jonesboro, Indiana) helped place the freedom seekers with local farmers. Perry Sanford and Reuben Stevens went to work for Stephen Bogue, sharing a cabin on his farm. [15]

In two stampedes occurring just weeks apart, a total of 33 men, women, and children had liberated themselves from two Kentucky counties. However, their freedom was far from secure. Just months later, Kentucky slaveholders arrived in southern Michigan in hopes of recapturing the freedom seekers.

FURTHER READING

Perry Sanford’s impromptu 1884 newspaper interview provides the most detailed eyewitness account from either of the two stampedes. [16]

Historian Carol Mull briefly addresses both escapes in her book, The Underground Railroad in Michigan (2010), but does not use the term “stampede” to describe either escape. Mull notes how the first group of 22 freedom seekers settled near Young’s Prairie in Cass County, Michigan, while also detailing the second group of freedom seekers using Perry Sanford’s recollection. [17]

[1] Zachariah Shugart Account Book, p. 101, Zachariah T. Shugart Papers, Huntington Library, [WEB].

[2] “Grand Stampede,” Cincinnati (OH) Commercial Tribune, April 28, 1847.

[3] “Grand Stampede,” Cincinnati (OH) Commercial Tribune, April 28, 1847; A Danville, Vermont newspaper reported an identical article, but attributed it to the Cincinnati Atlas. See “Grand Stampede,” Danville (VT) North Star, May 17, 1847. We have been unable to locate the original issue of the Atlas; it remains unclear which Cincinnati paper first coined the term.

[4] “Grand Stampede,”New York (NY) Evening Post, May 3, 1847; Providence (RI) Republican Herald, May 4, 1847; “Grand Stampede,” Hallowell (ME) Cultivator and Hallowell Gazette, May 15, 1847; “Grand Stampede,” Danville (VT) North Star, May 17, 1847; “Grand Stampede,” Prairieville (WI) American Freeman, June 9, 1847

[5] For more on the origins of the “stampede” terminology, see this post.

[6] “$3,125 Reward,” at “What’s In a Name–Johnson Family,” Amherstburg Freedom Museum, [WEB]. See Perry Sanford’s recollection for the name of Gardner’s/Casey’s daughter, Mary. Mary G. Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” Heritage Battle Creek, vol. 9 (Winter 1999), 78-81, [WEB]. Original interview with Perry Sanford from Sunday Morning Call, August 3, 1884. For more on the Gardner/Casey family, see Lewis Gardner/William Casey’s obituary, “Slavery Days Recalled,” Detroit (MI) Free Press, January 24, 1893.

[7] Zachariah Shugart Account Book, p. 101, Zachariah T. Shugart Papers, Huntington Library, [WEB]; Timberlake later named five freedom seekers, Jonathan, Nancy, Mary, Robert, and Gabriel, whom he accused Michigan abolitionists of harboring. See Thornton Timberlake v. Josiah Osborn, et al., January 10, 1849, National Archives Identifier: 12562895.

[8] Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” 78-81, [WEB]; Milton W. Graves v. Stephen Bogue, January 10, 1849, National Archives Identifier: 12561278.

[9] Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” 78-81, [WEB]. See African Americans of the Kentucky Borderlands database, https://omekas.bcplhistory.org/s/borderlands/item/15621.

[10] Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” 78-81, [WEB].

[11] Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” 78-81, [WEB].

[12] Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, The Reputed President of the Underground Railroad (Cincinnati, OH: Western Tract Society, 1876), 274, 297, [WEB].

[13] Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” 78-81, [WEB].

[14] John Rattiff to Wilbur H. Siebert, March 22, 1896, [WEB]; Charles W. Osborn to Wilbur H. Siebert, February 11, 1896, [WEB]; Charles W. Osborn to Wilbur H. Siebert, March 4, 1896, [WEB], all in Wilbur H. Siebert Papers, Ohio History Connection.

[15] Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” 78-81, [WEB]; Zachariah Shugart Account Book, p. 101, Shugart Papers, Huntington Library, [WEB].

[16] Butler and Martin L. Ashley (eds.), “Out of Bondage,” 78-81, [WEB].

[17] Carol Mull, The Underground Railroad in Michigan (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010), 109-113. Mull states that the first group of freedom seekers escaped “in late March.” She likely based this off of Sanford’s account; Sanford recalls escaping on the Monday after Easter (which would have been April 5, 1847). However, the newspaper reports, the slaveholders’ runaway ad, and court documents (cited above) all clearly concur that the first escape occurred on April 24, 1847. Moreover, Sanford’s recollection makes clear that it was slaveholders’ panic at the first escape which prompted the second group escape. In all likelihood, Sanford confused the exact time of the second escape.