The diminutive town of Tabor, Iowa in western Iowa served as a critical junction for freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad and abolitionists keen to end slavery on the western frontier. James Patrick Morgans’ biography of John Todd and the Underground Railroad (2006) not only focuses on Todd’s life story, but also offers valuable background on the antislavery networks that existed across Iowa. Morgan does not use the word “stampede” when referring to escapes of multiple enslaved people, however the book recounts several notable instances of group escapes.

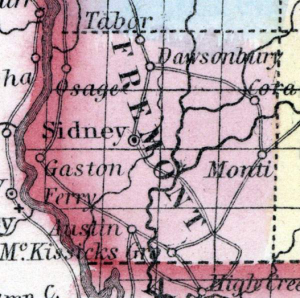

Tabor quickly became known as a hospitable place for freedom seekers. Todd and his town co-founders George Gaston and Samuel H. Adams, (all of whom were abolitionists), offered their time and resources to aid formerly enslaved people fleeing from Missouri.[1]

The town also served as a safe haven for antislavery warriors from Kansas territory, such as John Brown and James Lane. In effect, Tabor became their forward operating base. The settlement was close enough to Kansas that they could raid from it, but far enough away, that if things went poorly, they could also retreat to it. Brown even sent one of his injured sons back to Tabor to receive medical attention during the worst of the Bleeding Kansas period. For a period of time, Todd’s family also stored 200 Sharps rifles for Brown. Those rifles were later shipped to Virginia and used in the Harper’s Ferry Raid.[2]

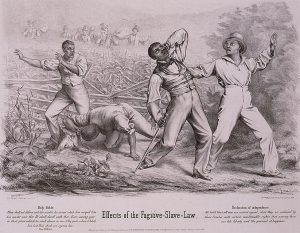

The first major group escape featured in Morgans’ book occurred in 1848 when nine enslaved people fled north from Missouri in search of freedom. Their intended destination was the Quaker town of Salem, Iowa. Ruel Daggs, the slaveholder, sent a large posse of slave catchers after them, however, and there was soon a physical confrontation and legal showdown in Salem.

Morgans discusses the legal and political repercussions of the case in some detail. In June, 1850, he local court in Burlington, Iowa decided that the Iowa residents aiding the escape were responsible for Daggs’ monetary loss and therefore required to reimburse him $2,900. The fines were never paid, however.[3].

Augustus Caesar Dodge (House Divided Project)

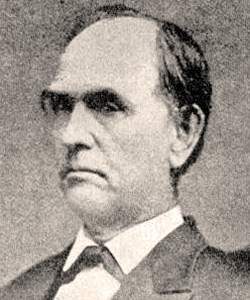

The Daggs Case was one of the last cases litigated under the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law. In the fall of 1850, after almost a year of debate, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 passed through Congress to shore up the 1793 law as part of the Compromise of 1850.[4] During the debates, Augustus Caesar Dodge, a United States Senator from Iowa, bragged that Iowa had a perfect record of compensating slaveholders for their escaped slaves, citing the Daggs case as an example. James Todd was a vehement critic of Dodge’s and used his platform in Tabor to actively work against what he considered to be the senator’s pro-slavery leanings. [5]

Another group escape featured in this book occurred on Independence Day. On July 4th, 1854, fellow Tabor abolitionists Gatson and Adams helped five enslaved people flee from their Mississippi slaveholder. The three adults and two children were led across the Nishnabota River on a fallen cottonwood tree and on to the next Underground Railroad station in Quincy, Iowa. When the slaveholder realized his slaves had made an escape to freedom, he rounded up a group of slave hunters. John Todd and some allies in Tabor not only assisted in the escape of the freedom seekers, but also then hindered the progress of the slave hunters by infiltrating their group. According to Morgans, some of the Tabor abolitionists volunteered to search the areas where they knew the freedom seekers to be hiding but then falsely reported that they were nowhere to be found. Despite some close calls, the escapees successfully made their way across Iowa, and eventually to Canada where they could not be captured.[6]

In fall of 1857, three armed, male freedom seekers on their way to Tabor and eventually to Canada were spotted by slave hunters south of Brownsville in the Nebraska Territory. A fight broke out between the groups. One of the slave hunters was killed while one of the escapees was badly injured and taken into custody. The injured slave survived his wounds and stood on trial in Brownsville but was acquitted of all charges. The two other escapees found their way to Iowa where they were shortly captured by another slave posse.[7]

John Brown (House Divided)

On December 20, 1858, John Brown and some of his men conducted a raid into Missouri to free a group of enslaved people. A slaveholder, David Cruise, was killed during the raid, but eleven enslaved people (eventually twelve, after a birth en route) successfully fled with Brown’s group to Kansas, then north to Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, and then eventually to Detroit, Michigan and Canada. The dramatic escape was applauded by abolitionists, but the killing of Cruise was controversial. Some citizens of Tabor adopted a resolution proclaiming,“…while we sympathize with the efforts for freedom, nevertheless, we have no Sympathy with those who go to Slave States, to entice away slaves, & take property or life when necessary to attain that end.”[8]

Morgans’ also details a group escape that took place in January 1859, when twelve slaves were captured near Holton, Kansas while attempting to cross into Iowa. Dr. John Doy, an Underground Railroad conductor who aided the escape was sentenced to five years in a Missouri jail. Kansas abolitionists soon freed him, however, in a shocking and successful rescue from St. Joseph, Missouri.[9]

Another major group escape occurred in March of 1860. Four, armed, male freedom seekers fleeing from the Cherokee Nation in modern-day Oklahoma made their way north to Iowa on their way to Canada and freedom. Upon hearing of the arrival of the escapees to Iowa, Gaston and others brought them into Tabor . Unfortunately, the conductors and escapees were discovered leaving Tabor and then consequently imprisoned. The conductors aiding them were given a trial date two days later, and the freedom seekers were imprisoned at an undisclosed location. Yet, in a surprising turn in events, the Tabor abolitionists discovered the location of the escapees, and as soon as the conductors were cleared of charges relating to aiding fugitive slaves, the men of Tabor found and released the four men from Oklahoma. In the end, all four freedom seekers successfully made it to Canada in a success for them and the abolitionist movement in Tabor.[10]

Morgans’ biography of John Todd serves as an excellent investigation into the mostly successful abolitionist network in Tabor, Iowa during the 1850s. Although many people in this region were opposed to their radical ideas, the abolitionist movement nevertheless conducted several liberation operations that involved helping large groups of freedom seekers avoid capture.

[1] James Patrick Morgans and John Todd, John Todd and the Underground Railroad: Biography of an Iowa Abolitionist (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 54.

[2] Morgans, 8.

[3] Morgans, 63.

[4] Library of Congress, “District Court of the United States for the Southern Division of Iowa, Burlington, June term, 1850 : Ruel Daggs, vs. Elihu Frazier,” Library of Congress, accessed July 2, 2019, [WEB].

[5] Morgans, 61.

[4] Morgans, 8-10.

[5] Morgans, 78.

[6] Morgans, 8.

[7] Morgans, 78.

[8] Morgans, 127-129.

[9] Morgans, 78.

[10] Morgans, 12-13.