In 1825, a family of five ran away from their plantation in Christ Church Parish, South Carolina. However, this family did not head North towards freedom. Instead they stayed in the woods near their home in hiding. For three years, they survived by trading at night with enslaved people still on the plantation and teaming up with other runaways to steal livestock and other goods.[1] When their parents were finally killed by a white mob, on a mission to end the “‘great evil’ of lying out,” the three children surrendered, returning into bondage with a fourth sibling who had been born while the family was in hiding. [2]

In Runaway Slaves (1999), John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger relate this remarkable story and others to help illustrate the complexities of running away from enslavement. Relying on a vast array of evidence, the noted scholars challenge the typical narrative of the freedom seeker by emphasizing the importance of temporary escapes within the region, rather than permanent escapes to freedom in the North or Canada. [3]

Franklin and Schweninger don’t use the phrase “slave stampede” in their work, however. Yet by emphasizing the type of maroon communities like the one that temporarily shielded the family from Christ Church Parish South Carolina, these scholars offer important insights for this project. In a more recent reference article, Schweninger writes, “Although their numbers fluctuated over time, pockets of outlying slaves, in the Caribbean known as Maroon communities, were always a part of the region’s landscape.” [4] This is a point that both scholars also suggest in their original study, claiming in passing that maroon communities, or “pockets of outlying slaves,” found refuge in nearly every state across the American South. They don’t specifically mention such pockets of resistance in Missouri, but it is a question worth pursuing: did any slave stampedes find at least temporary freedom inside Missouri, rather than by crossing the borderland into free territories?

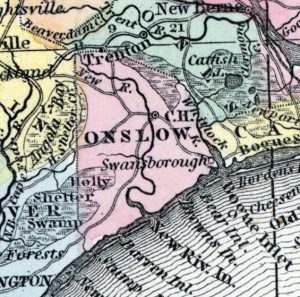

Onslow County North Carolina 1857

Frankin and Schweninger describe outliers who ran away for extended periods of time, returning only when they had no other choice or even in some cases after striking deals with their slaveholders. However, other times groups of runaways and outliers joined together creating semi-permanent groups or settlements of escaped slaves. In February of 1825, a group of 16 runaways, formed an encampment in the woods of Charleston District, South Carolina. By staying close to nearby plantations, the settlement was able to trade with enslaved people for vital supplies. These groups, often armed, terrified local white populations. In 1821, a band of runaways joined free blacks and caused an insurrection in Onslow County, North Carolina. White community members felt insecure about the safety of their lives, their families, and their belongings. This powerful depiction of white anxiety from Runaway Slaves described the Atlantic Coast in the 1820s, but it also suggests useful ways to explore similar reactions in Missouri following any “outbreak” of antebellum stampedes along the Mississippi River.[5]

[1] John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999): 101.

[2] Franklin and Schweninger, 101.

[3] Philip D. Morgan, review of Runaway Slaves by John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Indiana Magazine of History (1998): 155-56.

[4] Loren Schweninger, “Runaway Slaves and Maroon Communities,” Encyclopedia.com, [WEB]

[5] Franklin and Schweninger, 86, 87, 90, 102.