Joe William Trotter explores the creation and transformation of Black urban life by analyzing data from four cities along the Ohio River: Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Louisville, and Evansville. Trotter details how Black urban life is underscored by the history of slavery. Specifically, Trotter posits that the inception of Black urban life in the Ohio River valley was driven by the need for African Americans to secure their freedom and the freedom of their enslaved brethren.

For freedom seekers the Ohio River paralleled the biblical significance of the River Jordan as it had represented a path to the north, to freedom, to “the land of hope.” [1] Trotter reveals that the promise of the Ohio River did not live up to reality, not until Black Americans committed to creating a community that pursued freedom.

Taylor Alley or “Little Bucktown” — a predominantly black area in Cincinnati’s West End (River Jordan)

What had awaited freedom seekers north of the Ohio River were harsh systems that were designed to hinder any prospect of community building. Trotter analyzes a series of discriminatory anti-migration acts that prohibited “free blacks” from settling in these states. Trotter also cites Kentucky’s 1818 legislation that prevented free black men and women from immigrating to the state and the state’s 1834 law that forced black men and women to post bond in order to remain in the state. [2]

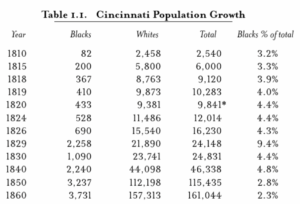

According to Trotter, the decrease in the African American population in the Ohio Valley from 1800-1850 serves to illustrate the intensity of these discriminatory acts. Cincinnati’s black population declined from 4.8 percent to 2.8 percent from 1840-1850. Pittsburgh’s population also declined from 4.0 percent to 3.3 from 1820-1840 but slightly increased to 4.3 in 1850. And Louisville’s black population declined from 36.4 to 16 percent from 1810-1850. Trotter attributes the population decline to mob violence, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the tendencies of slave catchers to enslave freedmen and women under false pretenses. [3]

Table of Cincinnati’s population from 1810 -1860 (River Jordan)

Simultaneously, however, the occupations of the black population diversified, as did the number of black property holders. According to Trotter, diversity in occupation was instrumental in the underground railroad. Trotter highlights the role of black employees at hotels in hiding runaway slaves and collecting information from slave owners who would often frequent their establishments. Totter includes the escape of two women in June 1848. He emphasizes that it was the assistance of the “blacks working at the Pittsburgh Merchants Hotel [that] helped two female slaves escape from a visiting planter.” [4] Trotter also details a letter from August 1841 from a Cincinnati “fugitive” to his enslaved wife. The letter served as an instruction for escape revealing the names of a barber, William O’Hara, and George (William) Casey, a riverman,who both aided in the escape of the fugitive’s wife and her friends. [5] Another operative, John Hatfield stated “I never felt better pleased with anything I ever did in my life, than in getting a slave woman clear, when her master was taking her from Virginia.” [6]

Trotter’s book contains valuable information about the development of black urban life, but does not include much information about group escapes. There was also no mention of the term “slave stampedes.”

[1] Joe William Trotter Jr., River Jordan: African American Urban Life in the Ohio Valley. (1st ed. The University Press of Kentucky, 2015), xiv

[2] Trotter, River Jordan: African American Urban Life in the Ohio Valley. 26

[3] Trotter, 37

[4] Trotter, 45

[5] Trotter, 45

[6] Trotter, 46