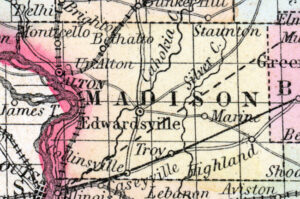

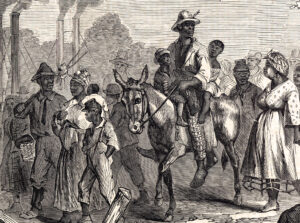

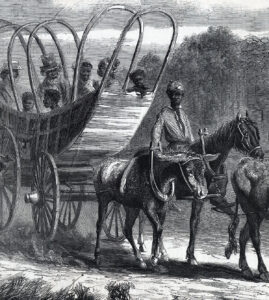

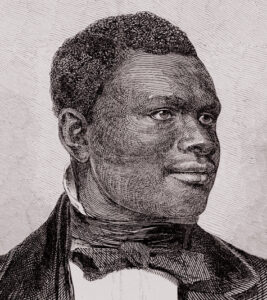

Joshua Glover, a fugitive slave from St. Louis, was rescued from Federal custody in 1854. (House Divided Project)

On March 10, 1854, a group of slave catchers burst into a rural Wisconsin home and seized a fugitive slave. Their captive, a man named Joshua Glover, had escaped from St. Louis, Missouri two years prior. Detained overnight in a Milwaukee prison, local abolitionists sounded the alarm and by morning Glover had a sizable crowd of supporters anxiously monitoring his fate. As the hours wore on, the crowd decided to take justice into their own hands, launching an all-out assault on the prison door with “planks, axes, &c.” Plowing through, they placed Glover in a carriage and whisked him away to safety. [1]

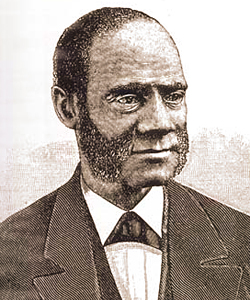

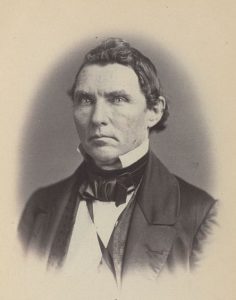

Yet the case was far from over. Accused of aiding Glover’s escape, Wisconsin abolitionist Sherman Booth was put on trial for violating the controversial Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, a case that ultimately worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. While Chief Justice Roger Taney upheld Booth’s conviction, it was clear that there were significant chinks in the law’s armor, especially when the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that the Fugitive Slave Law was unconstitutional, a “crowning, if fleeting achievement” for abolitionists. [2]

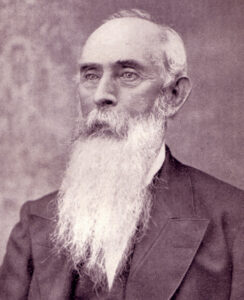

Wisconsin abolitionist Sherman Booth was tried for his alleged involvement in Glover’s escape. (House Divided Project)

Glover’s escape and Booth’s subsequent trials are among the many cases profiled by legal historian Steven Lubet in his book, Fugitive Justice (2010). Lubet’s book focuses in on three prominent cases involving the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850; the trial following the Christiana Riot in September 1851, the rendition of Anthony Burns in 1854, and finally the Oberlin Rescue of 1858, to show the evolution of abolitionist legal tactics during the 1850s. Over the course of the decade, Northern lawyers moved from pointed, technical arguments to moral appeals to a higher law. This tidal shift in legal resistance, Lubet argues, reflected changing attitudes among the Northern public towards slavery. By the late 1850s, abolitionist lawyers were willing to openly challenge the morality of the Fugitive Slave Law as well as slavery itself, an indication, Lubet tells us, of the Northern public’s growing anti-slavery impulse. In doing so, Lubet challenges the principal argument of Stanley Campbell’s book, The Slave Catchers (1970), which held that the Fugitive Slave Law was faithfully and effectively enforced. Through these cases and they way they were adjudicated, Lubet chronicles the mounting public discord against the law. [3]

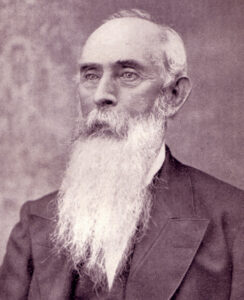

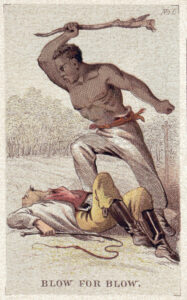

On September 11, 1851, African-Americans opened fire on Maryland slave owner Edward Gorsuch and his posse, in what is known as the Christiana Riot. (House Divided Project)

The first trial Lubet profiles came in the aftermath of the Christiana Riot in September 1851. The violent encounter actually stemmed from a group escape of four fugitives from the Maryland plantation of slaveholder Edward Gorsuch. Four of Gorsuch’s slaves, Noah Davis, Noah Buley and George and Joshua Hammond, had run away together in November 1849. This could be considered a slave stampede, though Lubet does not use the term. He does, however, speculate on their motives for escape, positing that the bondsmen had been stealing grain from Gorsuch, and perhaps ran away for fear that their theft had been discovered. [4]

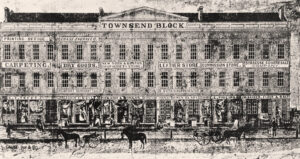

Castner Hanway, the key defendant in the Christiana trial, shown here later in life. (House Divided Project)

Nearly two years later, Gorsuch and a posse traveled to Christiana, in southern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, expecting to easily seize the fugitives. However, similar to other slave stampedes, the encounter quickly turned violent and took on a revolutionary meaning. Gorsuch’s four fugitives, joined by other local African-Americans, armed themselves and fought back, killing Gorsuch in the fray. Yet the ensuing trial (which is Lubet’s primary focus) did not revolve around who had shot Gorsuch, but rather Castner Hanway, a local miller who had rode to the scene of the conflict shortly before the first blood had been spilt. Among more than 30 others charged with treason for failing to “aid and assist” in recapturing the fugitives, Hanway was the first defendant placed on trial. His chief defense lawyer, Lancaster Congressman and noted abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens, made a tight, unprovocative argument for Hanway’s innocence. The strategy worked, and Hanway was acquitted, though his victory was not a repudiation of the law, writes Lubet, but rather a technical argument for the innocence of a specific individual, aided by the shaky credibility of one of the prosecution’s key witnesses. [5]

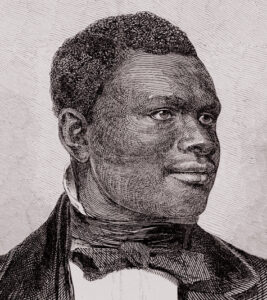

To considerable fanfare and outrage, fugitive slave Anthony Burns was remanded to slavery from Boston in 1854. (House Divided Project)

Lubet highlights two more cases, though both revolved around individual fugitives rather than group escapes. The first is the rendition of Anthony Burns in 1854, a fugitive slave who was seized in the streets of Boston. In a departure from Stevens’s technical defense, Burns’s defense lawyers argued that U.S. Commissioner Edward G. Loring had “ample room” to “interpret” the law, and rule in Burns’s favor. However, their efforts fell on deaf ears, and Loring declared that Burns was a fugitive and remanded him to slavery. [6]

The next landmark case involved an enslaved man from Kentucky, John Price, who had escaped to Oberlin, Ohio in 1856. He was captured by a slave catcher in 1858, only to be rescued by angry Oberlin residents. Although Price reached safety in Canada, a grand jury subsequently indicted 37 men for violating the Fugitive Slave Law, including 25 students, faculty and alumni of the prominently anti-slavery Oberlin College. In a contrast to both the Christiana and Anthony Burns cases, defense lawyers for the Oberlin activists would present what Lubet calls “the first forthright invocation of higher law in a U.S. Courtroom.” Only two defendants were actually brought to trial, and while both were convicted, their sentences were relatively light, especially that of Charles Langston, a black Oberlin graduate who boldly used his sentencing hearing to give vent to the higher law argument. The judge, Hiram Willson, practically “apologized” to Langston for enforcing the unpopular law, sentencing him to just 20 days in prison and a fine of $100. Lubet terms it “one small victory for the higher law,” asserting that although only partially successful in the courtroom, the higher law argument “helped to create an unbridgeable gap between the free states and the slave power.” [7]

Syracuse abolitionists stormed the second-story office of U.S. Commissioner Joseph Sabine in the first attempt to free Jerry, a Missouri fugitive. (House Divided Project)

Fugitive Justice makes a few references to Missouri escapes, including a brief allusion to John Brown’s December 1858 “raid” into western Missouri that helped free 11 enslaved people. Lubet discusses in considerably more detail the cases of St. Louis fugitive Joshua Glover and an even more famous Missouri runaway, William McHenry, commonly known as “Jerry.” He had escaped from Missouri and made his way to the abolitionist stronghold of Syracuse, New York. There, Jerry seemed to adjust well to freedom, working as a cooper. However, in October 1851 a slave catcher and U.S. marshals seized Jerry and brought him before U.S. Commissioner Joseph Sabine. Syracuse’s abolitionist populace was outraged, and stormed Sabine’s office, and later a jail, in order to free Jerry. While Jerry reached safety in Canada, indictments came down for 26 Syracuse men, resulting in just one conviction. Instead of treason, those involved in the “Jerry Rescue” were only charged with interfering with the law and assault. Lubet speculates that Federal officials were not eager to embark upon another difficult and time-consuming treason case in the “heartland of abolitionism,” where they were unlikely to prevail. [8]

The term slave stampede does not appear in Lubet’s book, nor does the concept of mass escapes. Fugitive Justice primarily covers legal cases that unfolded in Northern courtrooms, documenting the fallout from escapes, rather than the escape effort itself. Still, Lubet offers important insight into how fugitive slaves and their abolitionist allies constructed and evolved their legal defense strategies to align with changing public opinion in the North.

[1] Milwaukee Sentinel, quoted in, “Great Excitement–Arrest of a Fugitive Slave,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, March 24, 1854; Steven Lubet, Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 305-307.

[2] Lubet, 305-307.

[3] Lubet, 2-3, 5-6.

[4] Lubet, 55.

[5] Lubet, 57-64, 77, 91-131.

[6] Lubet, 190, 221-223.

[7] Lubet, 3, 6, 159, 232-239, 245-247, 250-254, 294-298, 327.

[8] Lubet, 86-90, 254, 305-307, 316.