Martin R. Delay’s Blake or the Huts of America (1859-1862) is often identified as the first black nationalist novel. It tells the story of Henry Blake as he escapes from slavery and tries to find his wife who had been sold away from him. However, Blake’s overarching goal was to unify the enslaved people and fight for freedom together. At first printed serially in a black owned newspaper, the chapters were later gathered and edited into a single work. Delany used the word stampede once in Chapter 30, “The Pursuit,” writing:

“The absence of Mammy Judy, Daddy Joe, Charles, and little Tony, on the return early Monday morning of Colonel Franks and lady from the country, unmistakably proved the escape of their slaves, and the further proof of the exit of ‘squire Potter’s Andy and Beckwith’s Clara, with the remembrance of the stampede a few months previously, required no further confirmation of the fact, when the neighborhood again was excited to ferment.” [1]

In this case, an incident that could be describe as a stampede reminds the community of a mass escape that had taken place a few months prior. Delany’s usage, however, provides insight into how slave holders responded to stampedes. He wrote that the town’s “advisory committee was called into immediate council, and ways and means devised for the arrest of the recreant slaves recently left, and to prevent among them the recurrence of such things; a pursuit was at once commenced.” [2] Delany’s fictional account illustrates real white anxiety surrounding stampedes.

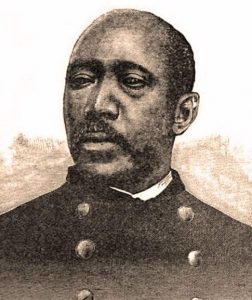

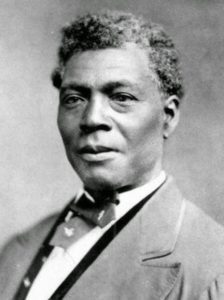

Frances E.W. Harper. (House Divided Project)

Iola Leroy or Shadows Uplifted by African American writer Francis E.W. Harper was published in 1892. The novel follows a mixed race family’s struggle with enslavement, freedom, and identity during the Civil War. The family “passed” as white. In the novel, Harper used the word ‘stampede’ three times. Each use was in relation to a single incident where a group of enslaved people plotted a mass escape to join the Union Army, camped nearby.

First, Harper wrote, “A few evenings before the stampede of Robert and his friends to the army, and as he sat alone in his room reading the latest news from the paper he had secreted.” [3] Here Harper did not use the term explicitly in connection with slaves, but Robert was an enslaved figure who was passing as white. His friends were formerly enslaved people.

The next instance reads, “When [the Union Army] came, there was a stampede to its ranks of men ready to serve in any capacity, to labor in the tents, fight on the fields, or act as scouts” (Harper, 36). This was a reference to runaway slaves. Harper added, “It was the strangest sight to see these black men rallying around the Stars and Stripes.” [4]

The final time that the term “stampede” appeared in the novel, it was when the character Iola announced that, “A number of colored men stampeded to the Union ranks, with a gentleman as a leader, whom I think is your brother.” [5]

[1] Martin R. Delany, Blake; or, The Huts of America (serial, 1859-1862; Boston: Beacon Press, 1970, reprint), Chapter 30, [WEB].

[2] Delany, Chapter 30.

[3] Frances E.W. Harper, Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (Boston: James H. Earle, 1892), 32, [WEB].

[4] Harper, 36.

[5] Harper, 196.