DATELINE: OCTOBER 31, 1852, NEAR LEXINGTON, KY

Eliza Crossing the Ohio River (Library Company of Philadelphia)

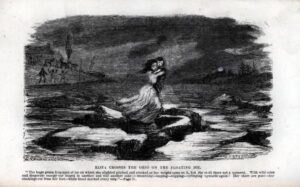

Late in the evening of October 31, 1852, when Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was still fresh in American minds, 25 enslaved men, women, and children, with the aid of a white accomplice, escaped from slavery in Bourbon County, Kentucky. They were heading toward freedom, first in Ohio and then perhaps beyond. Stowe had described the courage they exhibited in her novel. Eliza, her freedom-seeking protagonist from Kentucky, “was nerved with strength such as God gives only to the desperate.” [1] Uncle Tom’s Cabin challenged American views of slavery, and some historians view it as a catalyst for the Civil War. [2] But the 1852 Bourbon County “stampede” of freedom seekers offers perhaps an even more compelling reflection of how actual Black people helped to destroy slavery through their flight and resistance.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

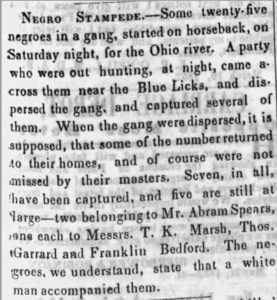

Throughout November 1852, readers as far away as Massachusetts read headlines of “Another Negro Stampede” from Bourbon County, just north of Lexington. The Paris, Kentucky Western Citizen had announced the event under the headline “Negro Stampede,” describing a “gang” of some twenty-five freedom seekers. Newspapers across Ohio echoed the term, with the Zanesville Courier announcing a “Stampede,” and adding that most of the escapees remained “non est comodibus in swampo,” using faux Latin to joke that the vanished freedom seekers were probably hiding in a swamp. [3]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Freedom seekers like the ones from Bourbon County could not enter free soil without first crossing the Ohio River, making it a physical and spiritual boundary between freedom and enslavement. The Ohio, often compared to the biblical River Jordon, had no bridges until after the Civil War. This meant the river could only be crossed by skiffs (boats), on foot if frozen, or by swimming. [4] The river’s turbulent waters, sandbars, and seasonal flooding made crossings even more dangerous. [5] Still, hundreds, probably thousands, of enslaved people had taken that risk before 1852.

During the summer of 1852, William Johnson, the secretary of the Vigilance Committee of the Anti-Slavery Society of Philadelphia, was arrested for passing counterfeit money to freedom seekers. Headlines from Bourbon County’s Western Citizen read “The Underground Railroad Out of Order – Conductor was conducted to the state prison.” Though the Kentuckian paper hoped that the article might prove to be a warning for other abolitionists, reports such as this only fueled anxieties among Kentucky enslavers about their human property and what they considered blatant violations of the laws of the Constitution. [6]

Despite “strong and active patrolls,” Kentucky slaveholders experienced relatively frequent escapes. By 1849, Bourbon County’s enslaved individuals made up 50% of its total population. [7] After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, historian Blaine Hudson argues that Kentucky freedom seekers began to flee more often in groups, sometimes including women, children, and older enslaved people. [8] By 1852, personal advertisements in local newspapers revealed the reward for a captured freedom seeker was typically $75 if they were caught in state, and $125 if retrieved outside of Kentucky. [9]

Enslavers’ fears about the growing trend of group escapes were borne out on October 31, 1852, when 25 men, women, and children escaped from multiple plantations. They escaped from the plantations of slaveholders Abram Spears, T.K. Marsh, Thomas Garrard, and Franklin Bedford. These enslavers were well–established members of the community. Jacob Spears, the father of Abram, established the first distillery in Bourbon County in 1790 and soon rose to fame as one of the first distillers of corn-based whiskey. [10] By 1850, Spears was recorded twice under the Federal Census Slave Schedules as owning a total of 78 enslaved people. [11] Thomas Garrard was a descendant of the second governor of Kentucky, who was remembered for naming the new county after the reigning House of Bourbon. [12] Aside from his business of cattle breeding, Garrard owned 17 enslaved workers. [13] Thomas K. Marsh, who was a silversmith known for crafting his own silver pieces, owned between 10 and 12 slaves. [14] Franklin Bedford owned 7 slaves at the time of the 1850 census. [15]

Mounted on horseback, the 25 freedom seekers made tracks for the Ohio River. The freedom seekers likely followed the Maysville Road corridor due to its proximity to abolitionist networks in southern Ohio. [16] However, these paths were known by friend and foe. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, our protagonist’s slave trader sought to take the road right to the river and boasted, saying, “I know the way of all of ’em, – they makes tracks for the underground.” An enslaved man searching with him responded that there were now two roads to the river, dirt and pike, but he was inclined to believe that Eliza took the dirt road, “bein’ it’s the least travelled.” [17] In the Kentucky border counties, there were estimated to be about 3,000 miles of escape routes with at least twenty-three points of crossing along the Ohio River mapped out by the Cincinnati Underground Railroad. [18] However, the landscape to freedom was not only treacherous, but it was ever evolving, and no secret to slave catchers.

In this case, it was not slave catchers, but a hunting party who thwarted the stampede. As the freedom seekers rode near the Blue Licks, a group of white Kentuckians out hunting at night confronted them. The hunters “dispersed the gang, and captured several of them.” At least four crossed the river opposite Fulton, a riverfront neighborhood in Cincinnati. [19] Fearing recapture, other freedom seekers “dispersed” and apparently crept back to their plantations before their enslavers noticed their absence. The Paris Western Citizen speculated that some of the 25 freedom seekers returned home, “and of course were not missed by their masters.” Other freedom seekers were not so lucky. Five days later, the Western Citizen reported that seven freedom seekers had been recaptured. [20]

Recaptured freedom seekers revealed to the Louisville Daily Courier that they had received assistance from a white accomplice. This was not uncommon. In 1855, local newspapers accused a white man and a free Black man of helping another group in a failed escape on skiff that sank in the Ohio River. The correspondent noted, “If they can get possession of the free negro he will probably be hung. The white man, if he is discovered, will be pretty apt to meet with the same treatment.” [21] Historian Blaine Hudson relates the story of another escape out of Bourbon County during this period that involved free Black leader Elijah Anderson, who reportedly spent the night in a tree with a freedom-seeking couple while bloodhounds and slave catchers passed nearby. [22]

AFTERMATH

Although seven of the freedom seekers were recaptured, at least five remained at large: two belonging to Spears, one to Marsh, one to Garrard, and one to Bedford. [23] In the days following the 1852 stampede, Kentucky slave catchers descended upon Cincinnati, Ohio on November 5, the Friday after the escape. [24] However, their efforts were unsuccessful, and there were no reports published of the recapture of the four freedom seekers who crossed into Fulton or the five claimed by Spears, Marsh, Garrard, and Bedford.

The freedom seekers likely received assistance from Cincinnati’s extensive Underground Railroad network. Levi Coffin, the self-proclaimed “President of the Underground Railroad,” operated a key safe house in the city and organized a vigilance committee to safeguard freedom seekers. Coffin contributed $50,000 of his own money to fund the protection of freedom seekers and collected double the amount from local businesses and professional men. [25]

While the slave catchers were still searching fruitlessly for the remaining freedom seekers, the Lisbon, Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle reported on another Kentucky escape that had begun a week before the Bourbon County stampede. Three enslaved people escaped from slaveholder Abraham Piatt in nearby Boone County, making their way through Cincinnati’s Underground Railroad network. Levi Coffin helped the freedom seekers board a northbound train, but the smooth-talking Donn Piatt, the nephew of slaveholder Abraham Piatt, happened to be aboard the same train and convinced the freedom seekers to accompany him to his home near West Liberty, Ohio. Only timely intervention from the local free Black community, who filed a writ of habeas corpus to rescue the freedom seekers, saved them from re-enslavement.

By November 1852, Kentuckians clearly felt the mounting pressure to prevent further escapes. Slaveholders from Mason and surrounding counties met “for the purpose of devising means to better secure the slave property of Kentucky” by means of the “formation of slave protection societies in each county of the State, especially those bordering on the Ohio.” The new slave patrols included funds to pay for expenses and stipends for those who captured runaways. [26] The newspapers described this as a real “plan of action.” [27]

Yet such activity did not deter the Kentucky freedom seekers or their vigilance supporters. The Voice of the Fugitive, a Canadian newspaper edited by Henry Bibb, reported that by the end of 1852, the Underground Railroad “never did a more thriving business than at present.” The newspaper reported that in merely the last ten days of November, twenty-six refugees from American slavery had crossed the Canadian border into freedom. [28]

Although the fates of the remaining freedom seekers from Bourbon County remain uncertain, it seems likely that they made it to freedom since no report publicized their recapture. Inspired by stories of freedom seekers escaping out of Kentucky, Stowe’s protagonist Eliza crossed the Ohio River, without shoes or stockings, “while blood marked every step” she took on the ice floes. Fueled by the determination to bring her son to free soil and encouraged by the dim vision of a man helping her up the bank on the side of freedom, continued her journey. [29] Later, safe at a Quaker home in Ohio, “She dreamed of a beautiful country,—a land, it seemed to her, of rest,” and woke to the sound of her husband’s footsteps and the understanding that her family was reunited and they would soon make their way to Canada. [30] Stowe’s mission to humanize Kentucky’s enslaved population revealed an ongoing theme of resilience and justice that surrounded the anti-slavery movement along the southern borderlands. Despite the efforts of Kentucky slaveholders to force men and women back into slavery, community organization and human perseverance kept the promise and hope of freedom alive.

FURTHER READING

For more on the Underground Railroad in this region and the tensions in the border states, see Richard Cooper and Dr. Eric R. Jackson’s Cincinnati’s Underground Railroad, as well as Blake W. Hudson’s Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland. These works provide in-depth analyses of the networks and individuals that made escapes possible.

NOTES

[1] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (New York: Ascent Audio, 2020), 53.

[2] Richard Cooper and Dr. Eric R. Jackson, Cincinnati’s Underground Railroad (Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Publishing Inc., 2014), 139; and J. Blaine Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland (Jefferson: McFarland & Co., 2002), 82. On the impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, see David S. Reynolds, Mightier than the Sword: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Battle for America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011).

[3] “Negro Stampede,” Boston (MA) New England Farmer, November 11,1852; and “Negro Stampede,” Paris (KY) Western Citizen, November 5, 1852; and “Stampede,” Zanesville (OH) Zanesville Courier, November 8, 1852.

[4] Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 62; Cooper and Jackson, Cincinnati’s Underground Railroad, 109.

[5] Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland, 12, 18.

[6] “The Underground Railroad Out of Order,” Paris (KY) Western Citizen, June 11, 1852.

[7] Karl Raitz and Nancy O’Malley, “Slavery, the Underground Railroad, and Hemp Production,” in Kentucky’s Frontier Highway, Historical Landscapes along the Maysville Road (University Press of Kentucky, 2012), 297; and “Kentucky’s Underground Railroad: Passage to Freedom,” KET Education, https://education.ket.org/resources/kentuckys-underground-railroad-passage-freedom/.

[8] Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland, 35.

[9] “Runaway Ad from Paducah KY,” Louisville (KY) Louisville Daily Courier, November 15, 1852.

[10] “Innovative Farmer and Distiller” image, from “Jacob Spears (1754-1825) – Find a Grave Memorial,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/200501849/jacob-spears; and ID: 1966, “Jacob Spears (1754 – ca. 1825),” ExploreKYHistory, https://explorekyhistory.ky.gov/files/show/1966; and Bourbon County 175th Birthday Celebration Corporation, Historical Scrap Book ; a Record of the Celebration of the One Hundred Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Founding of Bourbon County, Kentucky, May 13-20, 1961 (Paris, Kentucky, 1961), 10.

[11] “Abram Spears – Slave Schedules,” from Seventh Census of the United States 1850, images 1 and 4, via Ancestry.com.

[12] “Bourbon Stock for Missouri,” Paris (OH) The Kentuckian-Citizen, May 4, 1870; and Bourbon County 175th Birthday Celebration Corporation, Historical Scrap Book: A Record of the Celebration of the One Hundred Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Founding of Bourbon County, Kentucky, May 13-20, 1961, 7.

[13] “Thomas Garrard – Slave Schedules,” from Seventh Census of the United States 1850, image 2, via Ancestry.com.

[14] Raitz and O’Malley, Kentucky’s Frontier Highway, 187; and “Thomas K Marsh – Slave Schedules,” from Seventh Census of the United States 1850, images 11-12, via Ancestry.com.

[15] “Franklin Bedford – Slave Schedules,” from Seventh Census of the United States 1850, images 29, via Ancestry.com; and Atlas of Bourbon, Clark, Fayette, Jessamine and Woodford Counties, Ky (Philadelphia, January 1, 1877), G1333 .B3 1877, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA dcu, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3953bm.gct00130/.

[16] Raitz and O’Malley, Kentucky’s Frontier Highway, 297.

[17] Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 50-1.

[18] Cooper and Jackson, Cincinnati’s Underground Railroad, 77 and 81.

[19] “Another Negro Stampede,” Sandusky (OH) Sandusky Register, November 8, 1852.

[20] “Negro Stampede,” Louisville (KY) Louisville Daily Courier, November 4, 1852; and “Negro Stampede,” Paris (KY) Western Citizen, November 5, 1852.

[21] Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland, 86.

[22] Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland, 117.

[23] “Negro Stampede,” Paris (KY) Western Citizen, November 5, 1852.

[24] “Another Negro Stampede,” Sandusky (OH) OH Sandusky Register, November 8, 1852.

[25] Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland, 121-2.

[26] Hudson, Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland, 82-3.

[27] “Runaway Slaves,” Wilmington (OH) Clinton Republican, November 26, 1852.

[28] “Underground Railroad,” Greenville (OH) Greenville Journal, December 30, 1852.

[29] Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 72.

[30] Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 155.