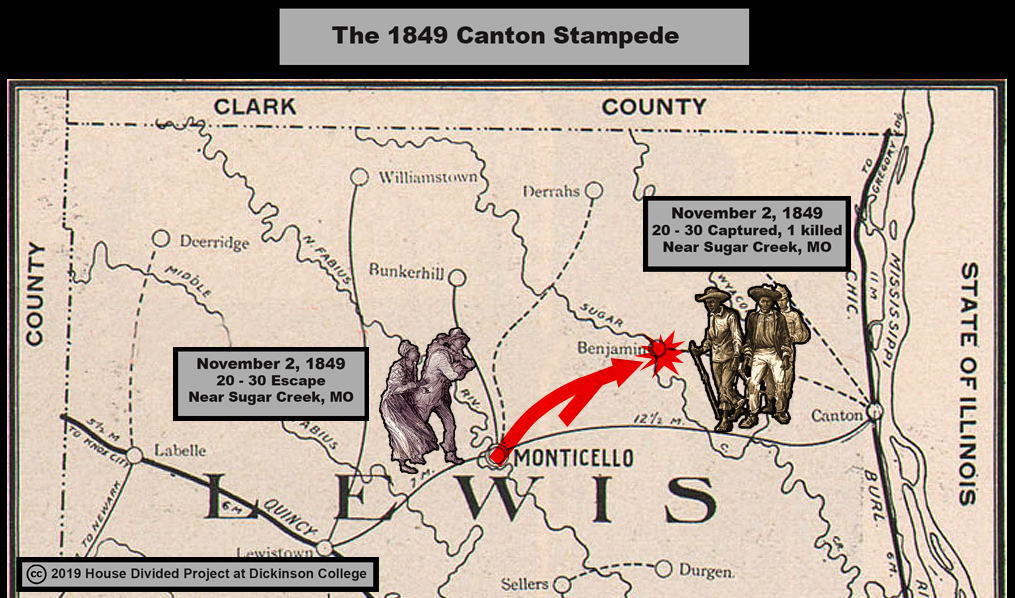

DATELINE: CANTON, MISSOURI, NOVEMBER 2, 1849

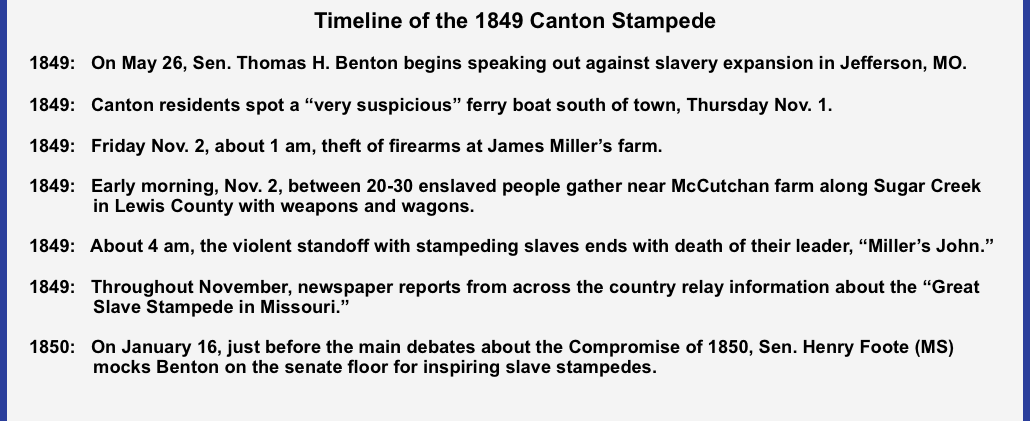

“We came nigh having a general stampede among the negroes in our county last night,” reported a correspondent from Lewis County, Missouri in November 1849. “About thirty-five of them banded together and provided themselves with arms, determined to fight their way out of the county.”[1] In a story that was full of dramatic intrigue, unexpected violence, wholesale capture and then the tragic break up of several African American families, it is remarkable that this attempted Missouri slave stampede on the eve of the Compromise of 1850 is not better known, nor more frequently taught in American classrooms.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

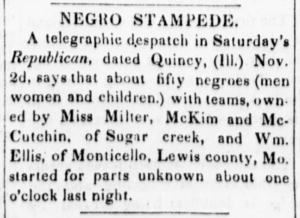

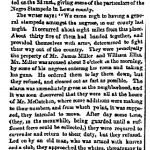

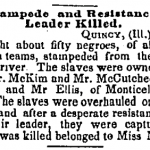

At the time, however, the failed escape of nearly three dozen enslaved people outside of Canton, Missouri was a national news story of considerable significance. The initial garbled reports, passed from Quincy, Illinois via the Missouri Daily Republican, and which appeared all over the country, claimed as many as fifty armed runaways from “both sexes.” “THE GREAT SLAVE STAMPEDE IN MISSOURI,” was how the North American and United States Gazette in Philadelphia labeled the tragic event. William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist journal, The Liberator, naturally attempted to evoke even more outrage with its coverage: “Another Chapter of Southern Atrocities and Horrors,” was its headline for the affair, which the newspaper also explicitly described as an attempted stampede.[2]

To view an interactive map of this stampede, check out our StorymapJS version at Knight Lab

To view an interactive map of this stampede, check out our StorymapJS version at Knight Lab

MAIN NARRATIVE

Canton, Missouri in Lewis County was a small village situated along the northeast corner of the state and bounded by the free state of Iowa to the north and by the Mississippi river and the free shore of Illinois to the east. White settlers from Virginia and Kentucky had first begun arriving in this region of Missouri during the 1820s and 1830s, bringing with them dozens of enslaved Africans to help develop the land for agricultural use.[3]

Lewis County was not plantation country. On the eve of the Civil War, only 19 slaveholders held more than ten slaves, and most of those had fewer than 14. In 1850, the county population included 1,206 enslaved people, 15 free blacks, and 5,357 whites.[4] The county’s largest slaveholder in 1850, Daniel Ligon, a Kentucky emigrant, owned 26 people. Other large slave holders of that era included E. W. Mitchell (17), James Miller (16), Eliza Morris (14), and J. W. Price (10).[5] Manumissions were rare in Lewis County, and those few African Americans who were freed were supposed to receive a court-appointed “trustee” to oversee their affairs. The first regular slave patrols in the county had begun in 1836, but only for about 24 hours per month.[6]

In June 1849, then-US congressman James Green summarized a view of the enslaved black families no doubt shared by most of his Lewis County constituents. “Subordination in a greater or lesser degree becomes inevitable in the very nature of things . . .. [and] has resulted to the black in immense good, and incalculable benefit, both moral and physical.”[7]

Yet events in Canton on Friday, November 2, 1849, barely five months later, called into question this politician’s assumption that slavery was either inevitable or somehow good for the enslaved. The stampede began with a theft. “A little before day on Friday morning last,” a newspaper recounted, “a negro man, belonging to James Miller, came into the house, ostensibly to make a fire. Before going out, Mr. Miller heard him step towards the gun rack, take something, and leave with caution.”[8]

John Ramsey, a guest at a nearby farm, also claimed to have heard at least two wagons coming and going about this time, which was “unusual” before daybreak. Ramsey was a cousin of John Newton McCutchan, a local slaveholder, and was soon planning to head out for California as part of that year’s “gold rush.”

The black man who had stolen the guns, called “Miller’s John,” was “very powerful [and] fierce as a grisly bear.”[9] An account written almost one hundred years later by W. K. Moore, the grandson of John McCutchan, identified John as one of two principal leaders of the stampede. The other, according to Moore, was Lin, an elderly woman owned by the McCutchans who worked in their kitchen. According to Moore’s recollection, John and Lin had been encouraging her ten-year-old grandson Henry to believe that he was capable of having prophetic visions. One of these visions, according to Moore, was that all of the whites would be killed and sent to heaven, “except my mother,” then a small child (the youngest McCutchan daughter), who was to be spared in order to become Henry’s wife.[10]

After the theft of the firearms, Dave, an enslaved child owned by the McCutchan’s, was soon “pressed . . . into telling” the now-panicked slaveholder that African Americans belonging to several neighboring families were first planning to kill the whites in their homes, and then gathering all of the willing blacks in the county, before making an escape to Illinois and then on to Canada. According to Moore’s account, “Lin had already served coffee in the kitchen, after mixing it with gunpowder to make them brave and with some of her magic potions that were to render them invulnerable.”[11]

Other farmers had learned of the plot and by daybreak more than 30 armed white men had tracked the freedom seekers to the McCutchan farm. “The negroes, amounting to between twenty and thirty, . . . had three guns, together with large clubs and butcher knives,” reported a local newspaper.[12] Beside those who had fled from Miller’s farm on the Sugar Creek, the group now included slaves owned by Judge William Ellis of Monticello, as well as Samuel McKim and James McCutchan, also of Sugar Creek north of Monticello.

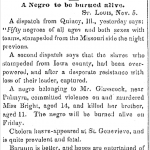

As the pursuers approached, the escapees presented “an obstinate defense . . . [demonstrating] the most dogged and settled hostility, [and] peremptorily refusing to yield.” The flashpoint came when the slaveholders, “after waiting and reasoning . . . until all patience was exhausted,” began to move toward the slaves.[13] Following a yell, Moore recalled being told that, “Lin and John rushed forward. John was armed with a sharp scythe blade bound to a short wooden handle, and Lin carried a bucket of boiling water, both dangerous weapons at close quarters. Two men raised their rifles and fired simultaneously, and John fell dead. Lin dropped her bucket and ran back to the others.”[14]

John was armed with a sharp scythe blade bound to a short wooden handle, and Lin carried a bucket of boiling water, both dangerous weapons at close quarters. Two men raised their rifles and fired simultaneously, and John fell dead. Lin dropped her bucket and ran back to the others.”[14]

Following the death of their male leader, the freedom seekers initially refused to surrender. The Missouri Republican claimed that the standoff lasted four hours.[15] But then, according to the most detailed newspaper account from Canton, the women “first gave up, and implored the men to do so likewise. Before the end of the time the men yielded, gave up their weapons, were bound and brought to Canton.”[16]

AFTERMATH

According to Washington K. Moore, the Lewis County slaveholders quickly buried the body of “Miller’s John” in a woods near Sugar Creek, a small tributary west of Canton and several miles from the banks of the Mississippi River. Moore claimed that as a young boy, he and his friends used to view that burial place “with eerie feelings.” Moore also recalled being fascinated as a child by a place called “Lin’s cave,” which was “a little mound back of a truck patch,” near the old McCutchan farm, where the cook Lin had reportedly kept her “roots and arbs” along “various trinkets” and “mysterious powders” that she had used for her conjuring.[17]

Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton

The failed Canton slave stampede contributed in its own small way to the nation’s growing sectional tensions over slavery. It certainly occurred in the midst of that antebellum crisis. Just two months before the Canton stampede, the North-East Reporter had warned local slaveholders to be on the alert for traveling northern Methodist preachers who might be “abolitionist emissaries . . . prowling wolves” to be driven out. Around the same time, the newspaper also attributed the escape of three slaves in Shelby County to the activities of US Senator Thomas Hart Benton, a free soil Democrat. Benton, according to the newspaper, might “at this very moment be concocting his hellish schemes, and persuading your negroes to leave you.”[18]

In the stampede’s aftermath, the Canton North-East Reporter quickly blamed the powerful Missouri senator, a recent convert to the anti-slavery movement. “When Benton came to the State last spring [on a speaking tour], all was peace—the negro was happy and contented with his master,” wrote the editors. “The Negro began to hope—became dissatisfied with his condition—began to plot to change it—and recent events are only some of the bitter fruits.” The North-East Reporter, backed by Benton’s Democratic rival, Congressman James Green, had been suggesting for months that Benton’s free soil politics were sowing dangerous discontent among Missouri’s enslaved population. As early as June 1849, the paper reprinted reports from a Jefferson City paper that “several slaves have been seen in possession of pamphlet copies of the Col’s [Benton’s] speech reading and discussing its merits.” Then in October, the paper warned readers to be on the “look out for a renewal of the scenes, on a larger scale, which some time ago spread alarm and terror through Lewis, Marion, and the surrounding counties, in North-East Missouri, and threatened with extinction, the whole slave property of the country.” In the aftermath of the stampede, the North-East Reporter reminded readers that Benton had spoke in nearby Monticello on Sunday, October 28, just days before the mass escape. “We don’t charge that his speech at Monticello was the immediate cause of the difficulty with our negroes,” the paper concluded. “But we do charge that his speeches through the State and his agitation of the question have produced it all…. His speech in Monticello but hatched the plot, which his agitation speeches elsewhere originated.” [19]

By contrast, the St. Louis Republican chose to focus most of its post-stampede ire on neighboring Illinois: “Almost every day our slaves are induced, by the persuasions of Abolitionists, to abandon comfortable homes, and to entrust themselves to the tender mercies of pretended friends, who are sure to fleece them of all their money before they quit them. We published yesterday a telegraph dispatch from Quincy, Ill., announcing the stampede of fifty slaves, in one company, from the county of Lewis, and no one will doubt that they were aided in their escape by citizens of Illinois.”[20]

The Palmyra Weekly Whig was even more specific in its accusations, reporting just days after the incident that local residents had first noticed “a very suspicious looking craft” on the river just below Canton on Thursday, November 1st. The newspaper claimed that the ferry boart, marked “U.S. Pounder,” had then quietly moved north of Canton on Friday evening but had since disappeared.[21] The implication was that it had been part of the underground network to help spirit away the enslaved. Moore’s recollected account suggests another darker possibility. His memory placed the small boat on the Mississippi River at Gregory’s Landing, about 14 miles north of Canton for several days before the attempted escape. “It was generally believed,” he wrote, “that men from the boat . . . prompted the plot in a cunning scheme to lure the Negroes on board the craft and, instead of freeing them, to ship them south to a slave market.”[22]

The only way to know for sure what was behind the Canton uprising would be to obtain testimony from the enslaved people themselves, but nothing has yet been recovered. Nor do we even know the fate of figures such as Lin, or her grandson Henry. The newspapers reported that the leaders of the revolt were all sold away to the Deep South, but otherwise there was no specific information about the African American families involved.

There were notable changes to Missouri law and politics, however. In January 1850, Thomas Hart Benton was openly taunted about the episode on the Senate floor during run-up to the Compromise of 1850 debates. Mississippian Henry S. Foote, an ardent pro-slavery southerner, called Benton “an indiscreet rhetorician” in the floor debates of January 16, 1850, blasting him for encouraging “the slave population” of Missouri “in twenties and forties” to “put themselves in full flight for the Father of Waters.” When Benton then stormed out of the chamber, Senator Foote responded gleefully, “See, Mr. President, he flies as did those deluded sons of Africa among whom his eloquence is reported to have awakened a regular stampede.”[23] Historian Diane Mutti-Burke also notes that the events in Canton had an impact on state law. “Acknowledging the potential for collective violence,” she writes, “Missourians enacted laws that made it illegal for slaves to congregate without a white person present, organized neighborhood slave patrols, and vigilantly watched for signs of trouble.”[24] By 1853, Missourians had also created an active Anti-Abolition Society. About this same time, Lewis County instituted more aggressive slave patrols.

These and other efforts to deter slave stampedes had mixed results, however. In 1859, there was another Lewis County stampede that received widespread attention, this time a group of eleven freedom seekers from LaGrange.[25] Yet the 1860 census listed only six freedom seekers absent from Lewis County. In the presidential election of that year, Lewis County voters also sought to sustain their peculiar institution: the Constitutional Union party of John Bell and the Southern Democrats led by John Breckinridge together attracted almost 75% of the vote. The eventual national winner, Abraham Lincoln of the anti-slavery Republican party, received only 48 votes—2% of Lewis County’s total.[26] President Lincoln was still alive in January 1865 when Missouri abolished slavery.

FURTHER READING

The best primary sources for the Canton stampede come from contemporaneous newspaper accounts. The most complete report appeared in the Canton North-East Reporter (microfilm only) on November 8, 1849 that was reprinted in the William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator under the headline “Another Chapter of Southern Atrocities and Horrors” and also in the Anti-Slavery Bugle on February 2, 1850. Other newspaper accounts from that fall and winter provide snippets of useful information, such as the names of the slaveholders and the number of freedom seekers. Numerous accounts use the term “stampede” to describe the affair. There was also an important recollected account published in 1958 in the Missouri Historical Review. W. K. Moore’s “An Abortive Slave Uprising,” written 14 years earlier in 1944, offers a particularly vivid account from the slaveholder’s perspective. Moore was the grandson of James Miller, on whose farm the stampede began. It is worth noting, however, that his narrative sometimes draws quite heavily upon the original newspaper account produced by the Canton North-East Reporter.

Secondary sources include a brief mention and useful context from Diane Mutti-Burke’s On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small-Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865 (2010) and also an important article by George R. Lee, “Slavery and Emancipation in Lewis County, Missouri,” Missouri Historical Review (April 1971), which provides a rich trove of background material on Lewis County. Eugene Genovese also quoted from one of the stampede participants (by way of Moore’s posthumous recollection) in his book, From Rebellion to Revolution: Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the Modern World (1979). This passage is revealing for students of slave resistance and worth repeating in full here: “Slave revolt leaders in the South had much less to fall back upon during the nineteenth century than their forerunners during the eighteenth or their counterparts in the Americas. They were influenced by conjuring but were normally skeptical of its extreme and politically dangerous forms. And they lived too close to their owners to deceive themselves. As one rebel slave recruit in Missouri explained, ‘I’ve seen Marse Newton and Marse John Ramsey shoot too often to believe they can’t kill a nigger.’” (p. 48).

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

- St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849 (GenealogyBank)

- Cleveland, OH Plain Dealer, November 6, 1849 (GenealogyBank)

- Philadelphia North American, November 7, 1849 (19th Century US Newspapers)

- Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 15, 1849 (Chronicling America)

- Palmyra, MO Weekly Whig, November 15, 1849 (Newspapers.com)

- Philadelphia North American, November 22, 1849 (19th Century US Newspapers)

[1] “The Lewis County Stampede of Negroes,” (St. Louis) Missouri Daily Republican, November 5, 1849. Also reprinted in “Negro Stampede in Lewis County,” Glasgow Weekly Times, November 15, 1849. The correspondent to the Republican wrote from Tully (adjacent to Canton) in Lewis County [WEB].

[2 St. Louis Missouri Daily Republican, November 5, 1849. “The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri” [WEB], Cleveland, OH Plain Dealer, November 6, 1849 [WEB]. Chicago Western Citizen, November 13, 1849. “Slave Stampede and Resistance –Their Leader Killed,” Baltimore Sun, November 7, 1849, [WEB]. “Stampede Near St. Louis,” Plaquemine (LA) Southern Sentinel, November 14, 1849 [WEB]. “Slave Stampede,” Fayetteville, NC North Carolinian, November 17, 1849 [WEB].“The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri,” (Philadelphia) North American and US Gazette, November 22, 1849 [WEB]. “Another Chapter of Southern Atrocities and Horrors,” The Liberator, January 18, 1850 [WEB].

[3] George R. Lee, “Slavery and Emancipation in Lewis County, Missouri,” Missouri Historical Review 65, no. 3 (April 1971), p. 295.

[4] Ibid., p. 305.

[5] Ibid., p. 303.

[6] Ibid., pp. 300-301.

[7] Canton North-East Reporter, June 21, 1849. Quoted in Lee, p. 302.

[8] Canton North-East Reporter, November 8, 1849, quoted in “The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri,” Anti-Slavery Bugle, 2 February 1850[WEB].

[9] Ibid., and W. K. Moore, “An Abortive Slave Uprising,” in Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 52, Issue 2, January 1958, pp. 123-26. Although not published until 1958, Moore’s account was written in 1944, a year before he died. Aside from his description of Lin and her activities, Moore’s account repeats almost word for word much of the account originally printed in the Canton North-East Reporter, November 8, 1849 and which was then reprinted in both The Liberator, January 18, 1850 and the Anti-Slavery Bugle, February 2, 1850.

[10 Moore. Some of the early newspaper reports also identified “Miss Miller” (Moore’s grandmother) as the legal slaveholder of John. See Concord (NH) Independent Democrat, November 29, 1849 [WEB].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Anti-Slavery Bugle.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Moore. The contemporary newspaper account identify John’s shooters as Captain J.H. Blair and John Fretwell. See The Liberator, January 18, 1850 [WEB].

[15] St. Louis Missouri Daily Republican quoted in “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, January 17, 1850.

[16] Anti-Slavery Bugle.

[17] Moore

[18] Lee, p. 310.

[19] “Citizens,” Canton North-East Reporter, June 23, 1849; “Runaway Negroes,” Canton North-East Reporter, October 4, 1849; Canton “Great Negro stampede!,” Canton North-East Reporter, November 8, 1849.

[20] Quoted in “The Peculiar Institution: Apprehension of Runaway Negroes-Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, January 17, 1850.

[21] “Negro Stampede,” Palmyra Weekly Whig, November 8, 1849 [WEB].

[22] Moore.

[23] Henry Foote quoted in Washington DC National Intelligencer, January 19, 1850 [WEB].

[24] Diane Mutti-Burke, On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small-Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 186.

[25] “Negro Stampede,” Glasgow Weekly Times, November 17, 1859 [WEB]; “Negro Stampede,” Press and Tribune (Chicago, IL), November 17, 1859 [WEB]. ‘”Stampede of Negroes from Lewis,” Louisiana Journal, 7 June 1860; Harriet C. Frazier, Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves and Those Who Helped Them, 1763-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 2004),102 [WEB].

[26] Lee, p. 311.