Archer Alexander courtesy of Mid Rivers Newsmagazine

In Missouri during the Civil War, the Union army sometimes employed enslaved people as spies. One of these espionage agents, Archer Alexander, made his escape from St. Charles, Missouri to St. Louis before his former slaveholders, the Hollmans, ever discovered that he was slipping the Union “information about [their] Confederate sympathies and guerrilla activities.” [1] After Alexander established himself in St. Louis, he asked to purchase the freedom of his family. The Hollmans refused. However, with the help of a neighbor and the protection of the Union army, the reminder of the Alexander family escaped and remained safely in St. Louis until slavery was abolished in 1865. [2] The Alexanders are perhaps a good example of wartime runaways who found freedom within Missouri state lines instead of heading across them.

Historian Dale Edwyna Smith’s African American Lives in St. Louis, 1763-1865 offers an exploration of the “unique status of African Americans in that gateway to the West, highlighting the greater freedoms and opportunity that persons of color had in the city than elsewhere in the state and the blurred lines between slaves and free.” [3] Smith focuses on the legal and social systems of African Americans, both free and enslaved, in St. Louis. In particular, she traces the laws restricting black mobility to their roots in the colonial French legal system, the Code Noir. Smith briefly mentions group escapes in Missouri, but she does not use the word stampede. Smith does note, however, that group escapes were “rare” and usually involved families. [4]

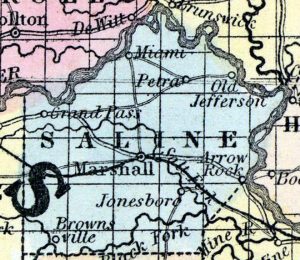

Map of Saline County 1857

Using runaway ads from the Missouri Gazette, Smith tells the story of the Journey brothers, three enslaved men who ran away together from St. Charles.[5] Another notable runaway ad, from slaveholder De Witt McNutt, described a mother and her young son, an individual man, and a husband and wife, who all ran together from Saline County. [6] But in addition to these types of advertisements, Smith highlights two other ways that enslaved people in Missouri gained freedom. One process involved manumission, the freeing of slaves by their slaveholder or the purchasing of “slaves for the [expressed] purpose of manumitting them.” [7] Another notable path to liberation in St. Louis was a contested legal process called “freedom suits.” At times, these two roads toward freedom intersected, such as in the case of the Milton Duty slaves.

Milton Duty wrote in his will his slaves were to be set free after his death. He moved from Mississippi to ensure that upon their freedom his slaves would be able to live in freedom. [8] However, a dispute over unpaid loans after Duty’s death halted the manumission of this group of 26. They were to be sold in order to pay off the debts Duty supposedly owed. And so, as a group, they sued for freedom in St. Louis Circuit Court in the spring of 1842. The charge was led by Preston and Braxton, enslaved brothers who seemed to have overseen organizing the Duty household in its move from Mississippi to Missouri. [9] The adults sued simultaneously on behalf of themselves and their minor children. In Preston’s case, he sued on behalf of two boys, whose parentage was unknown, but “as their next friend.” [10]

St. Louis Courthouse courtesy Missouri Historical Society

According to Smith, the “Duty case [was] striking for many reasons, not the least because in it, so many slaves simultaneously, and collectively, sued to be free.” [11] In 1845, there still was no resolution, so the Duty slaves petitioned the court again. [12] They made minor changes in the petition (adding Duty as their last name) and increasing the number of enslaved people suing for freedom, because James Duty was born. [13]

Tyler Blow, who famously purchased and freed Dred Scott after the Supreme Court denied his freedom suit, was also involved in the Duty Case. [14] In 1854, twelve years after the failed Duty case and sixteen years after Duty’s death, Blow freed Nicene Clark, whom he claimed he had purchased from the Duty estate. [15] Although in the end, the vast majority of the Duty slaves were never set free, this extraordinary case –a veritable legal stampede– seemed to have caused high anxiety within the state because that same year (1842) the state legislature “amended its laws to prohibit anyone from bringing slaves to Missouri from other states to set them free at a later date.” [16]

[1] Dale Edwyna Smith, African American Lives in St. Louis, 1763-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 165.

[2] Smith, 165.

[3] Robert Kett, “The Eventual Impossibility of Compromise,” Western Illinois Historical Review 8 (2017): 34, [WEB]

[4] Smith, 129.

[5] Smith, 127.

[6] Smith, 129.

[7] Smith, 130.

[8] Smith, 109.

[9] Smith, 109.

[10] Smith, 120.

[11] Smith, 119.

[12] Smith, 122.

[13] Smith, 122.

[14] Smith, 124.

[15] Smith, 125.

[16] Smith, 119.