1780 || Slavery in Cumberland County

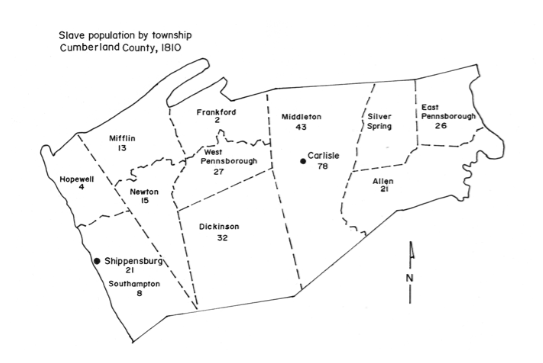

By 1780, during the year that Pennsylvania first adopted its gradual abolition statute (later amended in 1788), more than 300 enslaved people were living within the modern-day boundary of Cumberland County out of a total estimated enslaved population in the state of more than six thousand. We know this in part because the new law required slaveholders to register their slaves. In October 1780, for example, Rev. John King of Peters township (in present-day Franklin County) did just that, while also submitting a registration for “Molatto wench Poll[y] about 35 years old,” a woman who belonged to his father-in-law, Dr. John McDowell. Both King and McDowell were among the original trustees of Dickinson College. The enslaved population of Cumberland County declined over the subsequent years of gradual abolition, but not as fast as it did across the rest of Pennsylvania. By 1810, there were only a reported 795 slaves being held in Pennsylvania, but nearly 40% of them now resided in Cumberland County. By 1840, there were still 64 people being reported to federal census takers as slaves in Pennsylvania held under the terms of the 1780/1788 gradual abolition statutes.

Sources: John King Slave Return, Clerk of Courts Records, Cumberland County Archives, [WEB]; Michael McCoy, “Forgetting Freedom: White Anxiety, Black Presence, and Gradual Abolition in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1780–1838,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography vol. 136 no. 2 (April 2012), 141-170.

1783 || Slaveholders rule among early trustees

At least 60% of Dickinson’s founding board of trustees (elected in 1783) were slaveholders. These slaveholding trustees made crucial decisions about the college and were involved heavily in its earliest day-to-day operations, from securing land to approving bids for contract work. Slaveholders also made sizable donations, which helped keep the college afloat during its early years. With a few exceptions, most trustees were also Pennsylvania residents. While many of these men owned only one or two slaves, college namesake John Dickinson at one point held more than 50 enslaved people on his plantation in Delaware. Robert McPherson, a trustee living near present-day Gettysburg, owned 11 slaves, and trustee William McCleary of Washington County owned 7 slaves. Other slaveholding trustees were scattered across the region, including several who lived right in Carlisle.

Sources: For a complete list of trustees, click here. The statistics on trustee slave ownership were compiled from slave returns, registers and tax records; William Henry Egle (ed.), Pennsylvania Archives, (Harrisburg: William Stanley Ray, 1897), Series 3, vol. 14 [WEB], vol. 16, 772, 804 [WEB], and vol. 21, 5, 664, 732, 740 [WEB]; Minutes, September 15, 1783, Minutes of the Board of Trustees, 1783-1809, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 3, Box 1, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; Bedford County Slave Register, RG 47, Pennsylvania State Archives, [WEB]; Slaves in Bucks County, Dataset by Robin E. Wright, University of Pennsylvania [WEB]; Chester County Slave Register, Chester County Archives & Records [WEB]; Cumberland County Slave Returns and Slave Register, Clerk of Courts Records, Cumberland County Archives, [Returns and Register]; Lancaster County Index of Slave Owners, RG 47, Pennsylvania State Archives, [WEB]; Washington County Slave Register, RG 47, Pennsylvania State Archives [WEB]; Egle (ed.), Pennsylvania Archives, Series 3, vol. 21, 740 [WEB]; Washington County Slave Register, RG 47, Pennsylvania State Archives [WEB].

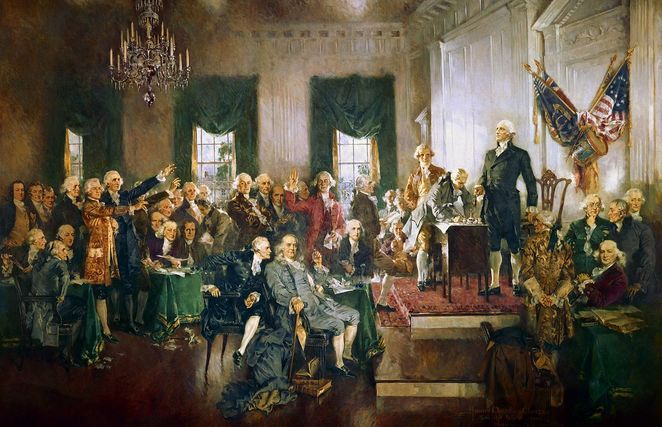

1787 || John Dickinson poses a difficult question

John Dickinson was born into a slaveholding family in 1732 in Maryland and continued to maintain his ownership of human beings well into his adulthood residing in Pennsylvania and Delaware. This created moral problems for him as sentiment in those places, especially in Quaker-dominated Pennsylvania, turned against slavery. Dickinson himself began to turn against the institution in both private and public. Between 1777 and 1781, he manumitted or freed over fifty enslaved people who lived on his Delaware plantation. However, that act was not entirely born out of benevolence or moral awakening. Dickinson quickly indentured his freed slaves as servants, holding them to terms of 7 to 21 years, as a kind of reimbursement for his role as their emancipator. Historians Gary Nash and Jean Soderlund write sharply that by this arrangement Dickinson had essentially “removed the stain of slaveholding from himself while keeping the profits of his blacks’ labor” well into his mid-60s. Still, Dickinson was not completely unaware of his own hypocrisy or the hypocrisy of other American founders who fought for liberty while profiting from slavery. He fought to include abolition measures in the new state constitutions in Delaware and Pennsylvania. During his attendance at the 1787 federal constitutional convention in Philadelphia, Dickinson also posed a difficult question for his fellow framers: “What will be said of this new principle of founding a Right to govern Freemen on a power derived from Slaves … [?]” He added, “The omitting of the Word [slavery] will be regarded as an Endeavor to conceal a principle of which we are ashamed.” Dickinson himself was certainly ashamed. He stood firmly against any protections for slavery, including the effort to extend the African slave trade and measures to award slaveholding states extra representation for their human property. But the politician also swallowed that shame, as he had done with his own personal efforts toward emancipation, in the name of being practical. Ultimately, he endorsed a Federal Constitution that protected slavery in states that still wanted to keep it.

Sources: Dickinson’s manumissions: Gary Nash and Jean Soderlund, Freedom by Degrees: Emancipation in Pennsylvania and its Aftermath, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 144-146; William Henry Egle (ed.), Pennsylvania Archives, (Harrisburg: William Stanley Ray, 1897), Series 3, vol. 16, 804 [WEB]. Anti-slavery proposals: William Murchison, The Cost of Liberty: The Life of John Dickinson, (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2013), 195-196. Constitutional convention: John Dickinson, “Notes for a Speech (II),” in James H. Huston (ed.), Supplement to Max Farrand’s The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987), 158-159, [WEB] and James Madison, “Notes on the Debates in the Federal Convention,” August 25, 1787, Avalon Project, Yale Law School, [WEB].

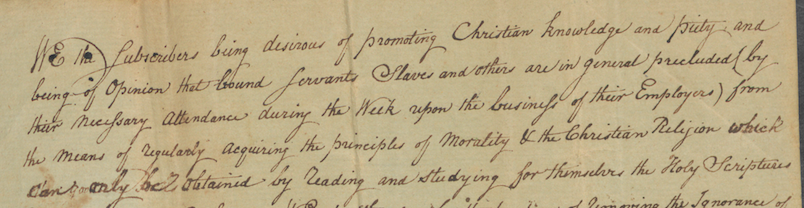

1788 || Local charity school excludes blacks

Many of Carlisle’s wealthiest slaveholders joined in helping to launch a local “charity school” in November 1787. Influential Dickinson trustees, including John Montgomery, Stephen Duncan and George Stevenson, all signed their names and opened their pocketbooks. Originally, this school was open to both white servants and enslaved blacks, “for the purpose of instructing poor persons in reading, who are engaged during the week in the business of their employers or masters.” Classes were held on Sunday evenings at the court house. However, attitudes about the inclusion of African-Americans soon changed. In May 1788, the subscribers met and decided to “set aside that part of the original plan, which respects the negroes.”

Sources: List of Subscribers to the Charity School, (filed under) O-Original-1788-1, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; Carlisle Gazette, November 28, 1787 [WEB], June 4, 1788 [WEB], January 7, 1789 [WEB], [Readex Early American Newspapers Database].

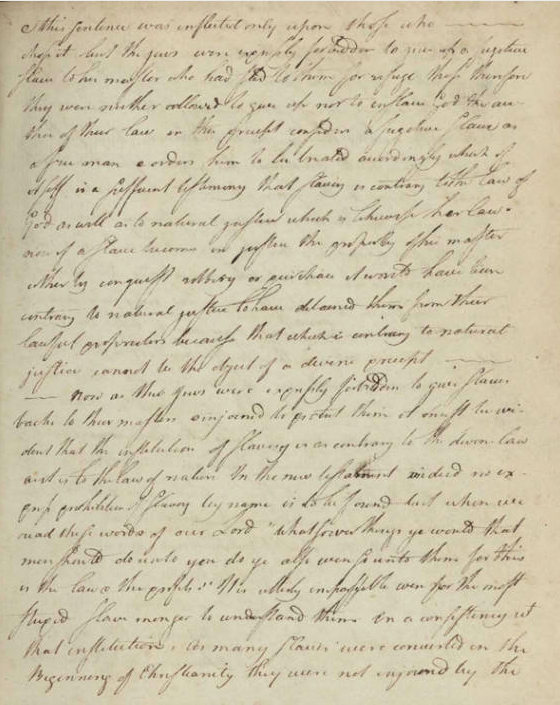

1789 || President Nisbet warns against slavery

Charles Nisbet, a noted scholar and leader in the Scottish enlightenment, became the first president of Dickinson College in the 1780s and served until his death in 1804. Yet in some ways, he never fully adapted to American culture. One aspect of American life that he particularly hated was slavery. In one notable lecture from 1789, President Nisbet referenced the famous Somerset Decision (1772), a landmark case which had declared that slavery could not exist on English soil, because there was no positive law in place to enforce the institution. Nisbet observed bitterly to Dickinson students that the opposite was actually true in the new United States, where “when a free man lands in America he immediately becomes a slave and often for more than 7 years.” Nisbet was also a vocal critic of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, at one point criticizing in the classroom the “meanness of the Slave Trade which is now almost monopolized by a nation which spoke with some justice of being the freest in the world.” In a class held in March 1789, Nisbet warned his students that the very presence of slavery portended violent consequences for the young nation. Slaves lived with “concealed hatred” and “masked resentment” towards their masters, Nisbet declared, according to the student notes which have survived, and “the least spark may animate to destruction.” Nisbet returned to this theme in his private letters as well. In 1792, after he had received several “valuable Publications” from the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, headquartered in Philadelphia, he observed gloomily that the pamphlets would probably be “bound up together” in Dickinson’s library, “& till a Generation shall arise that have a Zeal for the Liberty of others, as well as their own,” they would remain virtually untouched. Nisbet commented that he believed it would take a “Negroe War, which may probably break out soon… to enlighten the Consciences of the friends of Liberty in this Country.”

Sources: Samuel Mahon Notebook, Lecture 172, n.d., 511, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, [WEB]. Mahon Notebook, Lecture 170, April 14, 1789, 490, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, [WEB]; Mahon Notebook, Lecture 144, March 26, 1789, 158-160, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, [WEB]; Charles Nisbet to William Rogers, August 17, 1792, photostat, Nisbet Drop File, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, original at Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

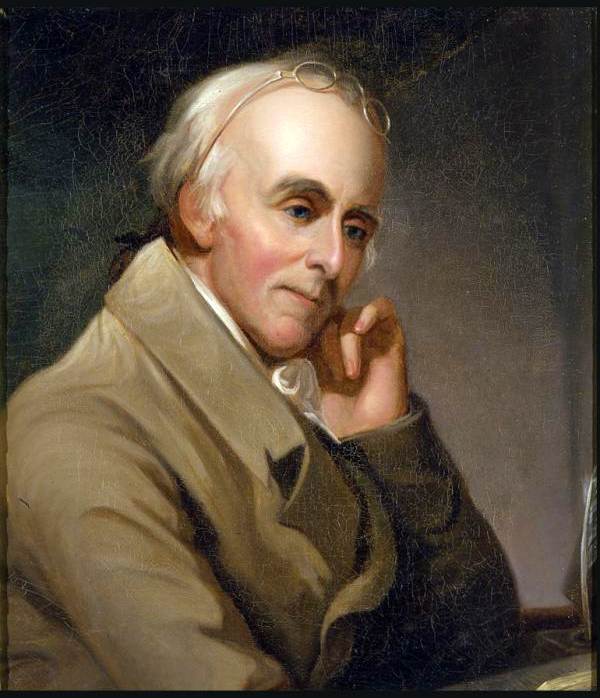

1794 || Dr. Rush (slowly) frees his own slave

Dickinson College founder Benjamin Rush was well known for his strong antislavery views. Yet, Rush came from a slaveholding family, married into a prominent slaveholding family from New Jersey (the Stocktons) and held slaves within his own household as a leading doctor in Philadelphia. Rush owned one particularly important man named William “Billy” Grubber, whom he had purchased sometime before July 23, 1776 (when he first mention Billy in a letter to his wife). Grubber was a key household servant for Rush, and a trusted aide who traveled with him on occasion (such as when the doctor ventured out to Carlisle in 1784 for the inaugural Dickinson board of trustees meeting). Rush eventually manumitted or freed Grubber in 1788, but set the final date for Billy’s freedom more than six years later, in 1794. He claimed that this delay was necessary so that he could receive a “just compensation for my having paid for him the full price of a slave for life.” Grubber died in 1799 as a free man. However, following the news of his former servant’s passing, Rush made a notation in his commonplace book that revealed a great deal about his underlying prejudices. The great enlightenment medical pioneer wrote coldly that “when I first bought his time,” (a misplaced euphemism for slavery), Grubber was “a Drunkard and swore frequently.” Then Rush claimed in transparently self-serving fashion, that, “In a year or two he was reformed from both these vices, and became afterwards a sober, moral man and faithful and affectionate Servant.” Grubber was so “faithful,” boasted Rush, that he had once “obtained some of my hair secretly, and had it put in a ring” as a souvenir. Whether or not such claims had any kernel of truth is impossible to know, because Grubber himself left no testimony of his own in the historical record –at least none that we have discovered yet.

Sources: 1788 statement quoted in David Freeman Hawke, Benjamin Rush: Revolutionary Gadfly (Indianapolis and New York: The Boss-Merrill Company, Inc., 1971), 361; Reflection on Billy: Benjamin Rush Commonplace Book, June 17, 1799, in George W. Corner (ed.), The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush, (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1948, reprint 1970), 246. L.H. Butterfield, “Dr. Benjamin Rush’s Journal of a Trip to Carlisle in 1784,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 74 (Oct., 1950): 443-456.

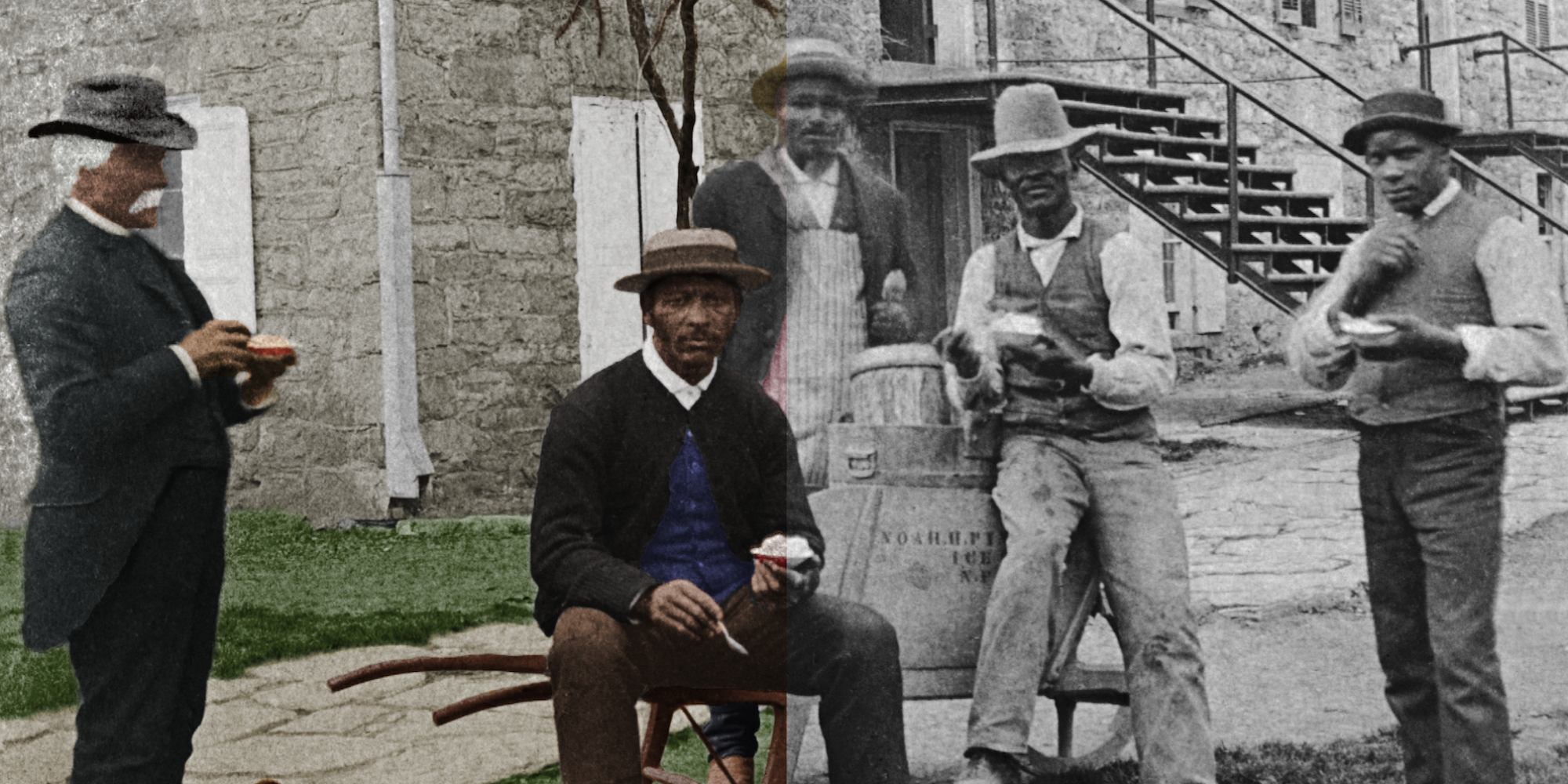

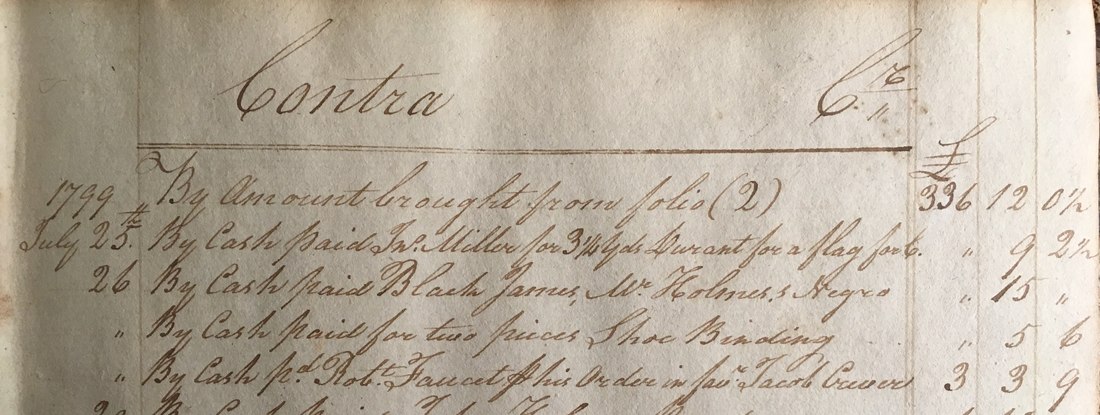

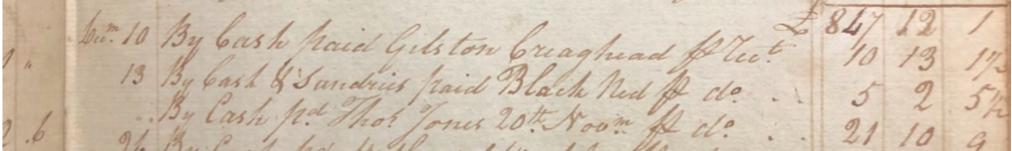

1799 || Enslaved labor helps to build new campus

Slaveholders were closely involved in the construction of the first college buildings, between 1798-1805, supplying both materials and enslaved labor. While Dickinson College did not own any enslaved people, local slaveholders hired out their slaves to the college. We know for certain that Carlisle slaveholder John Holmes hired out his slave “Black” James to the college in 1799. When Holmes journeyed to Baltimore on behalf of Dickinson that year, James accompanied him. Upon their return, Holmes billed Dickinson for 16 days of James’s time. Later, James was hired out to work on the construction on campus. More Cumberland County slaves were likely involved in the construction. In 1799, a man referred to as “Black Ned” was also paid for work, but his status (as free or enslaved) is left unspecified in the college records. Later, in the construction of West College, John Welch, a slaveholder from neighboring Franklin County, supplied wooden posts. Similarly, Charles McClure, a slaveholding trustee from nearby Middleton township, agreed to deliver 3,000 bushels of sand. Both men surely used enslaved labor in providing their services to the college.

Sources: BLACK JAMES: Bill of John Holmes, April 16, 1799, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 6.4.33, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; Payment to “Black James, Mr. Holmes’s Negro,” July 26, 1799, Financial Ledger, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 6.1.1, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; and special thanks to CoryYoung, PhD candidate in history at Georgetown University who first discovered the entry for “Black James.” BLACK NED: Payments to “Black Ned,” June 23 and December 13, 1799, Financial Ledger, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 6.1.1, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; OLD WEST: Contracts for Goods and Services, West College 1803, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 5.4.4, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; For McClure’s relationship to other board members and slave owners, see Carla Christiansen, “Samuel Postlethwaite: Trader, Patriot, Gentleman of Early Carlisle,” Cumberland County History, 31 (2014): 34, [WEB].

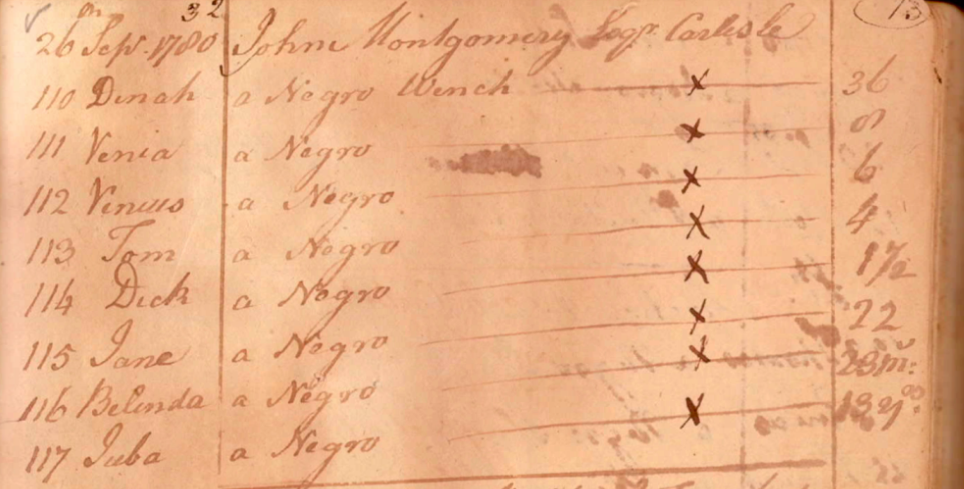

1808 || Founding trustee buys & sells slaves

More than any other figure except for Benjamin Rush, John Montgomery, a native of Ireland, was responsible for helping to organize the establishment of Dickinson College. Montgomery, who served for years as sheriff of Cumberland County, was also the longtime treasurer of the Dickinson board of trustees and always among the college’s most active and influential board members during the late eighteenth century. Unlike either Rush or John Dickinson, however, Montgomery was also an unrepentant slaveholder. In 1780, Montgomery registered eight slaves, making him one of Carlisle’s largest slave owners. When Dickinson’s Board of Trustees met at Montgomery’s Carlisle house in April 1784, for example, trustees were no doubt in close contact with his enslaved servants. Before the decade was out, five additional slave births increased Montgomery’s holdings in human property. In 1783, a girl named Violet; girls Patience and Phillis in 1786, and males Darby and Harry in 1788, all added to Montgomery’s wealth. Montgomery also sold slaves and broke apart families, which even in that era came with a terrible stigma. In 1787, he advertised an enslaved woman and three young children for sale. [5] But perhaps most revealingly, in 1808, even as he neared death, Montgomery willed that all his property should be sold, “Except my negro man Thomas and my waggon [sic] and horses which I allow to be kept for the use of the family until the next spring.”

Sources: Minutes, May 2, 1792, Minutes of the Board of Trustees, 1783-1809, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 3, Box 1, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; For more on Montgomery’s relationship with Rush, see Lisa Rainier, “Benjamin Rush and his Relationship with John Montgomery in the Founding of Dickinson College,” November 15, 1982, Essays, History, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; Slaveholder Register, Clerk of Courts Records, Cumberland County Archives, [WEB]; Carlisle Gazette, July 25, 1787, Readex Early American Newspapers Database; John Montgomery, will dated September 18, 1800, Book G-340-341, Cumberland County Register of Wills, Carlisle, PA.