PUBLIC MEMORY AT DICKINSON

The college is named after John Dickinson, because, as a state historical marker near campus puts it, he was once legendary as the “penman” of the American Revolution. There are paintings of Dickinson at the College Archives and inside Old West. His personal story is also featured on the college website and described in greater detail at the Archives website. Yet currently there is no public marker or any explanatory text acknowledging his role as a major colonial-era slaveholder or describing how he came to emancipate his own slaves.

The college is named after John Dickinson, because, as a state historical marker near campus puts it, he was once legendary as the “penman” of the American Revolution. There are paintings of Dickinson at the College Archives and inside Old West. His personal story is also featured on the college website and described in greater detail at the Archives website. Yet currently there is no public marker or any explanatory text acknowledging his role as a major colonial-era slaveholder or describing how he came to emancipate his own slaves.

BRIEF PROFILE

From Dickinson College Archives: “Dickinson enjoyed the serene childhood of a southern plantation. His family were English, having settled in the seventeenth century in Maryland; Dickinson himself was born in Talbot County, on November 2, 1732. He grew up at Poplar Hall, the elegant brick mansion of his father, Judge Samuel Dickinson. There, surrounded by flat fields of wheat and tobacco, young Dickinson received private tutelage in Latin….During the War for Independence, Dickinson enlisted as a private in the Continental Army, having been a colonel in the provincial militia. He was proud of his service, however undistinguished. Congress had fled to York, and Philadelphia fell to General Sir William Howe. Dickinson had moved his family to safety in Delaware; in 1777 British troops burnt Fairhill. Dickinson’s company served under General Caesar Rodney, notably at the Battle of Brandywine. Dickinson’s genteel Quaker relatives disapproved but convinced themselves he was Rodney’s aide-de-camp.In 1781 Dickinson was elected president of Delaware; the next year he resigned that post to be elected president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. While Dickinson was president of Pennsylvania, his old colleague from the Congress, Benjamin Rush, suggested founding a new college in Cumberland County. Rush approached Dickinson about naming the new college ‘John and Mary’s College,’ in honor of the president and his lady. Dickinson, appalled at the parallel with William and Mary, demurred, saying that the new Republic should avoid allusions to monarchy. Rush won approval for calling the college ‘Dickinson.'”

FURTHER READING

- Dickinson College encyclopedia: Dickinson, John (1732-1808)

- Calvert, Jane E. Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Flower, Milton E. John Dickinson: Conservative Revolutionary. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983.

- Nash, Gary B. and Jean R. Soderlund. Freedom by Degrees: Emancipation in Pennsylvania and its Aftermath. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. (see pp. 144-146)

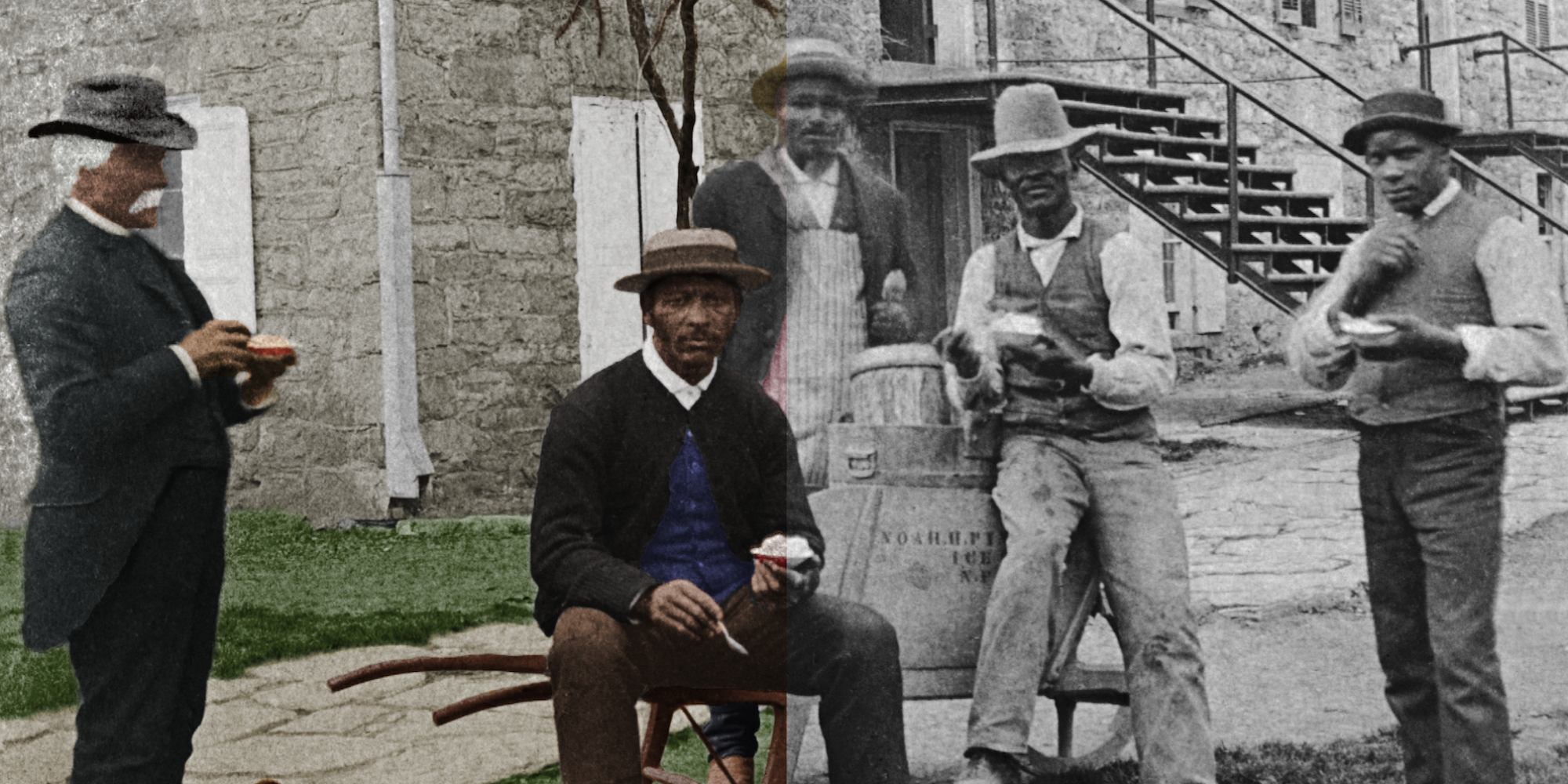

IMAGE GALLERY

PRIMARY SOURCES

-

- Manumission of John Dickinson’s Slaves, 1777-1779, Historical Society of Pennslvania [WEB]

- These initial manumission papers provided conditional emancipation for dozens of Dickinson’s slaves who resided on his Delaware plantation

- John Dickinson, “Notes for a Speech (II),” in James H. Huston (ed.), Supplement to Max Farrand’s The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987), 158-159, [WEB].

- Here Dickinson writes out a denunciation of the hypocrisy of the Framers that he planned to deliver at the 1787 constitutional convention

- Manumission of John Dickinson’s Slaves, 1777-1779, Historical Society of Pennslvania [WEB]