Author Anita Wills Blog About her Civil War Ancestors

“No officer in this regiment now doubts that the key to the successful prosecution of this war lies in the unlimited employment of black troops. Their superiority lies simply in the fact that they know the country, while white troops do not, and that they have peculiarities of temperament, position, and motive, which belong to them, alone. Instead of leaving their homes and families to fight they are fighting for their homes and families, and they show the resolution and sagacity which a personal purpose gives.”[1]

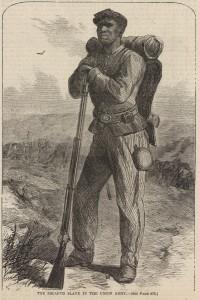

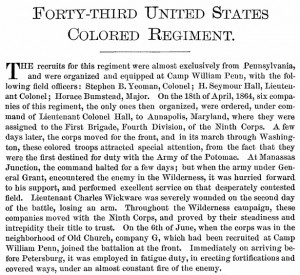

Approximately 180,000 African-Americans, comprising One Hundred sixty-three units, served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and many more served in the Union Navy. Native Americans served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT), while some, mainly in the south, fought for the Confederates. Black Indians, served in colored regiments with other African American and Native American soldiers.[2]

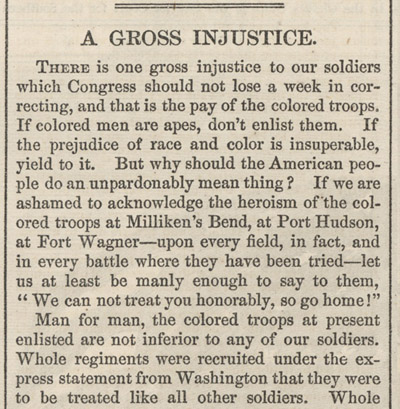

After the Civil War, many USCT veterans struggled for recognition and had difficulty obtaining the pensions rightful to them. The Federal government did not address the inequality until 1890 and many of the veterans did not receive service and disability pensions until the early 1900’s. My ancestors, Henry Green and Uriah Martin, applied for Pensions, and left documents of their lives before and after the Civil War. When it came to Henry Green, and Uriah Martin, my mother told us they came from the Welsh Mountains. She passed down what she was told, and we did not doubt that what she said was true. The census records and documents on our ancestors, are proof that her version was correct. She stated that, Uriah Martin’s brother, William Penn Martin settled in California after the Civil War.

I found information on a William Martin in Yolo County California, who was born in Pennsylvania. He fit the profile somewhat but I have not proved him to my satisfaction. I was thrown off by the racial designation of white on the 1870 census. There was another William Martin at Michigan Bar, in Sacramento, and he too was from Pennsylvania, and is listed as white. Great Uncle William Martin’s trail in California has grown cold, and remains a mystery to our family.

The Martin and Green men, lived closer to the land then Walter Samuel, and were a little more rugged. Henry Green had tattoos of Anchors on both forearms, a fact that was mentioned in his Civil War Records. They were remnants of the Natives, Free Blacks, and whites, who lived in and around the Welsh Mountains. The Welsh Mountain is a Community, which cuts through Lancaster and Chester County in Southeastern Pennsylvania. The Mountains were a place of refuge for escaped slaves, free blacks, and Natives avoiding deportation to reservations. Many of the whites who fled into the mountains were criminals, or running from Indentured Servitude. During Pennsylvania’s slave period, African slaves and indentured whites both sought freedom in the Mountains. They soon made up a rugged group, now known as, Tri-Racial Isolates.

My mother passed the history of our ancestors through stories she told, when we were children. It was a means of keeping us occupied during the cold Pennsylvania Winters. She spoke of the Civil War and our ancestors who were part of the Colored Troops. We learned about the Civil War in History Class, and looked through the books, for mention of the Colored Troop. There was no mention of them in the history books, nor in the books in our library. I knew that my mother would not make up tales about the family. It was not until 1983 that I ordered copies of Uriah Martin and Henry Greens Civil War Records. My mother and I poured over those records to glean information.

The Green and Martin families, were descendants of those rugged mountain folks, but lived in both worlds. They would come down and work on area farms and then head back to the mountains. In later years, the young people came down, married, and/or joined the Military. My Grandfather Martin was the last of our line to live in the Mountains. I remember going up there and seeing the haze over the trees. It was absolutely beautiful, and breathtaking, something that is hard to find words to describe. There were cases of people who wandered in the Welsh Mountains told Harrowing tales, of seeing Ghost like figures, and being shot at. There are even stories about people going in the Mountains and disappearing without a trace. These days there are only a few descendants, of the original people left on the Mountain. Developers have swept in, building upscale homes for Middle Class Families.

The Underground Railroad Colored Soldiers and the Welsh Mountains

My mother spoke about our Welsh Mountain ancestors, having been under the protection of William Penn. Her Paternal grandfather was named William Penn Martin, after his fathers brother, William Penn Martin Senior. They and their ancestors, considered themselves, “Penn’s Indians”, even after the land was taken, and most Natives were shipped to Reservations out west. They were the Conestoga and Susquehanna who lived along the Rivers and Creeks in Chester and Lancaster County.

The area where they hunted, and fished, was also part of the Underground Railroad, which led from Southern States like, Virginia and Maryland to points north. The Underground Railroad had many stops throughout Southeastern Pennsylvania, because of it’s proximity to the south. My Great-Great Grandfather, Robert Pinn, was one of the unsung heroes of the Underground Railroad. He and his family were free blacks living in Virginia, until 1853, when the fled to Columbia (Lancaster County), Pennsylvania. He was a vocal Baptist Minister in Virginia and continued to Minister in Columbia, until he was forced to flee to Burlington New Jersey. Robert Pinn was from a long line of Virginia’s Free Colored Population. His grandfather, Rawley Pinn was a Revolutionary War Soldier, who fought at The Siege of Yorktown. His wife, Elizabeth Jackson-Pinn, was also a descendant of Free Persons of Color, and her grandfather, Charles Lewis was a Sailor and Soldier during the Revolutionary War. Continue reading →