An undated portrait of Louis Hughes found in his autobiography.

(By Mary Chobanian, Dickinson College, Class of 2012)

Louis Hughes was born in 1832 to a white plantation owner and black slave in Charlottesville, Virginia. His autobiography entitled Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom, published in 1897, documents the daily lives of southern slaves. Jack McGee (or McGehee), a cotton plantation owner in Pontotoc, Mississippi, purchased Hughes at a young age. As a young adult, Hughes later traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, to work on the construction of McGee’s second home. He tried multiple times to run away but failed. Late in the Civil War, Hughes and other McGee slaves were sent to labor at a salt works in Tombigbee, Alabama before they were sent back home near the end of the war as the Confederacy began to crumble. Hughes finally received liberation from slavery late in 1865, after the war had already finished, when the Union occupation forces finally began to secure northern Panola County, Mississippi. At first, Hughes was compelled to flee himself to Memphis before returning to Mississippi in a dramatic confrontation with his former masters.

[cetsEmbedGmap src=http://maps.google.com/maps/ms?msa=0&msid=214983518559597788700.0004be5fef46b70010825&ie=UTF8&t=m&ll=36.031332,-83.935547&spn=12.426868,18.676758&z=5&output=embed width=350 height=425 marginwidth=0 marginheight=0 frameborder=0 scrolling=no]

Louis Hughes’ extensive travels throughout the South, from birth until emancipation, 1832-1865.

Though Hughes discussed at length the mundane lives of slaves, he shed even mire light on slave families and the challenge of reuniting with loved ones after emancipation. As was common among slaves, Hughes never found his mother again. But in June 1865 Hughes was determined not to leave his wife and children behind. In the company of another newly freed slave and with the help of two Union soldiers, Hughes returned to Panola to bring his family to safety. Hughes recalled how the Union soldiers berated the southern whites who were trying to keep his family enslaved:

“Meanwhile the soldiers had ridden a round a few rods and came upon old Master Jack and the minister of the parish, who were watching as guards to keep the slaves from running away to the Yankees. Just think of the outrage upon those poor creatures in forcibly retaining them in slavery long after the proclamation making them free had gone into effect beyond all question! As the soldiers rode up to the two men they said: ‘Hello! what are you doing here? Why have you not told these two men, Louis and George, that they are free men –that they can come and go as they like?’ By this time all the family were aroused and great excitement prevailed. The soldiers’ presence drew all the servants near. George and I hurried to fill up our wagon, telling our wives to get in, as there was no time to lose –we must go at once. In twenty minutes we were all loaded. My wife, Aunt Kitty, and nine other servants followed the wagon. I waited a few minutes for Mary Ellen, sister of my wife; and as she came running out of the white folks’ house, she said to her mistress, Mrs. Farrington: ‘Good-bye, I wish you good luck.’ ‘I wish you all the bad luck,’ said [the mistress] in a rage. But Mary did not stop to notice her mistress further; and joining me, we were soon on the road, following the wagon.” (pp. 182-83)

Hughes and his family soon arrived in Memphis. He never forgot the growing crowd of liberated slaves he found in that city upon upon his return:

“Thousands of others, in search of the freedom of which they had so long dreamed, flocked into the city of refuge, some having walked hundreds of miles…Everywhere you looked you could see soldiers. Such a day I don’t believe Memphis will ever see again–when so large and so motley a crowd will come together” (Hughes, 187).

Hughes regretted his inability to remember the names of the two Union soldiers who helped him retrieve his family in Mississippi. However, in his gratitude and praise of their courage and kindness, he explains the difficult reality of familial separation:

“If I could not have gone back, which I could never have done alone, until long after, such changes might have occured as would have separated us for years, if not forever. Thousands were separated in this manner – men escaping to the Union lines, hoping to make a way to return for their families; but, failing in this, and not daring to return alone, never saw their wives or children more” (Hughes, 188).

As Hughes as said, newly freed slaves found it difficult to reconnect with their broken families. Living in constant fear of being split up, many slave families were separated as a result of the internal slave market. However, a number of those who gained freedom, believed they could return to the South to retrieve their families. Hughes explains that “Others still desired freedom, thinking they could then reclaim a wife, or husband, or children. The mother would again see her child. All these promptings of the heart made them yearn for freedom” (Hughes, 79). While some emancipated slaves created pamphlets and advertisements in search of family members, others like Hughes risked returning to the South and being recaptured–whether to return to slavery prior to the end of the war or to share crop on a plantation during the Reconstruction era.

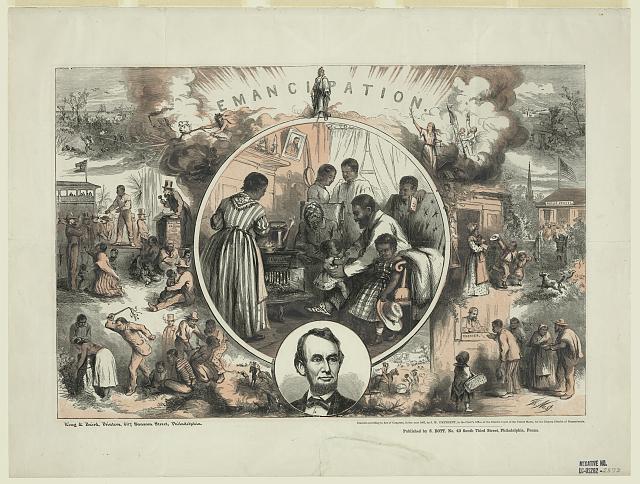

Artist Thomas Nast celebrates the emancipation of southern slaves by depicting a reunited black family, c. 1865.

After successfully finding his wife and children, as well as other extended family, Hughes traveled north to Cincinnati, Chicago, and Canada in order to reconnect with loved ones and to find employment. His family finally settled in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he worked as a professional nurse and wrote his autobiography.

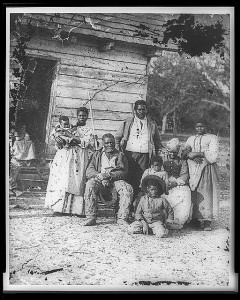

“Five generations on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina,” by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, c. 1862. Photo from the Library of Congress.

“Five generations on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina,” by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, c. 1862. Photo from the Library of Congress.

Further Reading

Ash, Stephen V. A Year in the South: Four Lives in 1865. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. [Features the story of Louis Hughes]

Dunaway, Wilma A. The African-American Family in Slavery and Emancipation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003. [Available in full on Google Books]

Hughes, Louis. Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom. Milwaukee, WI: South Side Printing Company, 1897. [Available in full on Google Books]

Manning, Chandra. What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, And the Civil War. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007. [On Union soldiers fighting to free slaves]

Hughes dictated his book to his daughter, who put it on paper. Her manuscript was edited by “a gentleman of this city.” So says an article in the Milwaukee Sentinel of Nov. 29, 1896.