- This session will review advanced tips for improving your close reading essays and videos

- NOTE: Prof. Pinsker will be away on vacation following this session and until after the Aug. 8 due date. You can still email him questions or share drafts, but put everything into the body of the email for him to review or post it at WordPress. No attachments.

FRI AUG 8 : Second close reading due in evening

- Be prepared to discuss the Oakes book at this session and plans for your final essays

- Reminders and discussion about for submission of final essay

-

Grades available by email within about a week

-

Transcripts sent by regular mail within about two weeks

-

Prof. Pinsker available for recommendation letters after grades

SUMMARY FROM JULY 31 ZOOM:

Your next assignment is due on Friday, Aug. 8, a second close reading reflection. And your final assignment is a comparative essay on the respective reform strategies of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass and the lessons they suggest due by Friday, Aug. 22. That essay will be the equivalent in length of about two close reading reflections and will require thoughtful secondary source research. The final essay will be posted online at the same project site and with supporting images, but no video will be required. Between those two deadlines, you should be reading James Oakes’s book: The Radical and The Republican, which is the one secondary sources that everyone will need to use in their final essay. We will talk about the book in detail on Aug. 13.

Your next assignment is due on Friday, Aug. 8, a second close reading reflection. And your final assignment is a comparative essay on the respective reform strategies of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass and the lessons they suggest due by Friday, Aug. 22. That essay will be the equivalent in length of about two close reading reflections and will require thoughtful secondary source research. The final essay will be posted online at the same project site and with supporting images, but no video will be required. Between those two deadlines, you should be reading James Oakes’s book: The Radical and The Republican, which is the one secondary sources that everyone will need to use in their final essay. We will talk about the book in detail on Aug. 13.

- Zoom sessions are mostly designed to be helpful as check ins and enhanced learning opportunities for research and writing strategies. But remember the real work is in drafting your assignments and consulting with Prof. Pinsker via email (pinskerm@dickinson.edu)

General writing advice for historical close readings:

-

- Pick a text that engages your historical imagination

- Stick to simple past tense

- Use Chicago-style footnotes (and consult Methods Center for more details

- SAMPLE FOOTNOTES FOR OAKES:

- [1] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007), 27.

- [2] Oakes, Radical 31.

- SAMPLE FOOTNOTES FOR WEBPAGES (adapted for online publication):

- [3] “Phillis Wheatley, On Being Brought from Africa (1773),” Knowledge for Freedom Seminar [WEB]

- SAMPLE FOOTNOTES FOR OAKES:

-

- Always guard against plagiarism, especially when you paraphrase. REMEMBER: never summarize a source while you are looking at it. Close the book or the tab and do it from memory.

- Advice for strong openings:

- Consider attempting a narrative vignette built around a snippet of quotation

- Provide brief but effective summary context of the document under study

- Then pivot to a clear thesis statement that offers an original interpretation about the significance of the author’s writing strategy

- Advice for strong text summaries:

- Summarize the entire text (or text excerpt) deftly using both paraphrase and snippets of quotation

- Don’t forget to describe the format of the text

- Always acknowledge if you are focusing only on an excerpt

- Advice for strong context sections:

- Good context requires some outside research using high quality secondary sources

- Judge secondary sources by the expertise of the authors (requires BYLINES) and whether the format has been peer reviewed (requires academic publishing) or at least edited (requires professional publishing)

- Always start with context information about author and audience and then consider expanding into time period essentials –but always be judicious and don’t overwhelm your analysis with too much context

- Advice for strong subtext analysis:

- The best way to decode subtext is to consider what’s left out

- The easiest way to understand what’s missing from a document is by wide-ranging comparison. For example, how is this document different from earlier documents written by the same author? How does it compare to similar documents written during the time period by other authors? What about comparing the document to previous classic documents (such as the Declaration of Sentiments with the Declaration of Independence)?

- Remember to compare backward in time (not forward). This is a historical close reading exercise.

- Advice for strong closing arguments:

- Return to the opening vignette or idea

- Reframe the original thesis into something thoughtful –don’t just restate it.

- Multi-Media Reminders

- Don’t forget to include two to three images with captions and clickable credits, expandable (attach to media file) and formatted neatly within paragraphs or between them

-

- Don’t forget a short document video produced in WeVideo and including clear, well read audio narration, a compelling music track, carefully selected and high quality images, some nice production elements such as call out text or transitions, and a well organized credit slide

SUMMARY FOR AUGUST 13TH (AND AUGUST 20TH) ZOOMS

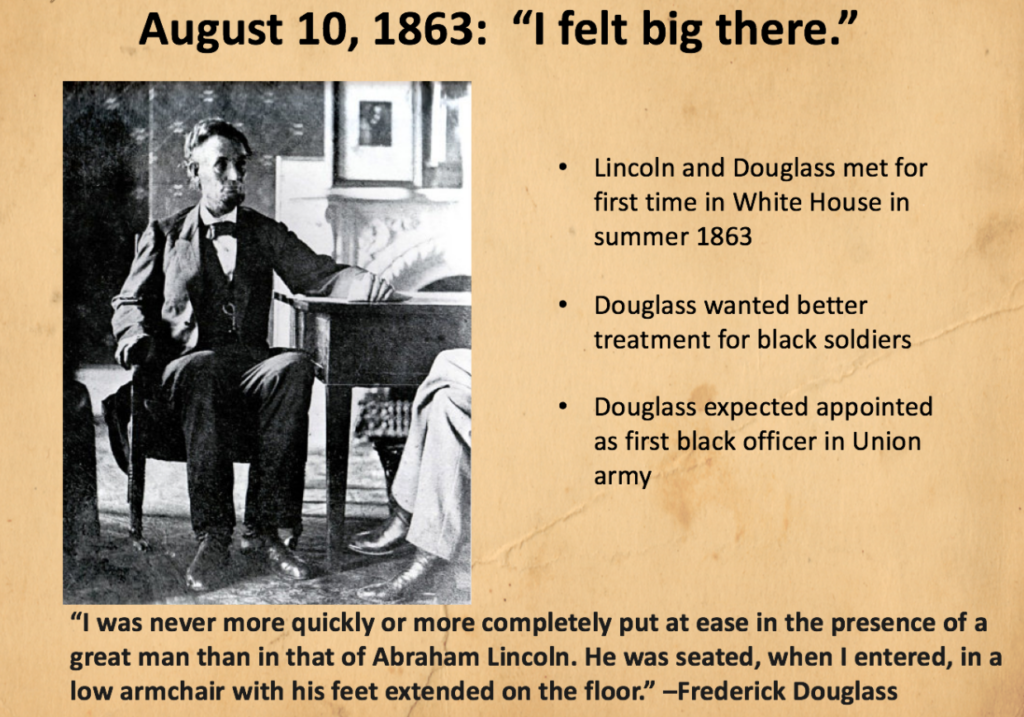

Lincoln and Douglass meetings (Chapter 6: “My Friend Douglass”)

- August 10, 1863

- August 19, 1864

- March 4, 1865

See Other-Lincoln Douglass Debates page for additional background

Chronology of Emancipation:

- Oakes, chapter 4: “This Thunderbolt Will Keep”

- Oakes, chapter 5: “We Must Free the Slaves or Be Ourselves Subdued”

- Syllabus page on Saving Union: Lincoln and Emancipation

- Timeline page on Pinsker Civil War course

Advice for the final Lincoln-Douglass essay:

“and a final essay (about 1,000 to 1,500 words or roughly 4 to 6 pages) that draws lessons about how best to achieve change in American democracy through comparing and contrasting the antislavery strategies of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.”

- Read the Oakes biography carefully, especially the introduction, the conclusion and any sections which cover any of the documents which you plan to feature. Think about the differences between radicals and moderates, or between reformers and politicians (as Oakes puts it). Consider how Lincoln and Douglass differed, and where they converged, and then ask if there’s any insights or lessons from that experience about how best to achieve change in American democracy.

- As always, focus your strongest writing energy on crafting an appealing opening –one that would engage fellow students. Consider using a narrative vignette or striking statement or epigraph. Provide essential context and then pivot to an organizing thesis statement that offers a clear interpretation.

- Example of thesis framework

- Here is an example from Jordyn Ney’s essay: “The question thus became who they should appeal to most to ignite change and when they should take action to ensure a positive outcome. Much like today, American politics was a balancing game between when to wait and when to act.”

- The body of the essay should have a clear structure, reflecting change over time or chronology and a clear sense of research effort.

-

Essays should include a descriptive title and sub-headings when helpful, properly captioned and credited images as well as Chicago-style footnotes, citing wherever relevant the primary source texts from the course syllabus as well as any secondary sources provided by the program, most notably James Oakes’s dual biography, The Radical and the Republican (2007).

-

Always remember to strive for balance: between seeing the big picture (Lincoln vs. Douglass) and highlighting your leading examples (always focus on just a few moments), between making an argument (your interpretation) and providing the essential background (context necessary for understanding by your readers), and between understanding the past and appreciating its possible insights for the future.

-

Practical tips:

-

Remember our debate on the final day of the campus program and feel free to borrow ideas from that exchange

-

Also feel free to use revised material from your earlier close reading essays when relevant

-

Make sure that you use at least a few compelling (and properly captioned and credited) images but do not create videos or other multi-media tools

-

Don’t plagiarize by mis-paraphrasing or by using AI-generated text.

-

-

Try to send or share with Prof. Pinsker drafts (full or partial –and at least of your opening paragraph). He will read them up to the afternoon of Thursday, August 21.