DATELINE: CHICAGO, APRIL 3, 1861

Shortly after 6:00 a.m. on the morning of Wednesday, April 3, 1861, U.S. Deputy Marshal George L. Webb led an armed “posse” of six men up the stairs of a home at 251 South Clark Street in Chicago. Pounding on the door, Webb aroused a family of four freedom seekers, who had escaped from near St. Louis, Missouri about a month earlier––38-year-old “Onesimus” Harris, his 21-year-old wife Ann and two young children, George, aged four, and Charles, aged one. [1] As the frantic cries of “kidnapper” rang out in the early morning air, the marshal and his men quickly seized the Harris children, who were rushed downstairs and forced into an omnibus waiting outside. Meanwhile, Harris and his wife fiercely resisted their would-be captors, giving Webb’s men “a lively time.” Yet they too were ultimately subdued. The “stout” Harris was “manacled, and his elbows tied behind his back,” before being “dragged down” the stairs into the same vehicle, while Ann Harris, “wrapped in a quilt for decency’s sake,” was hurriedly shuffled into the omnibus. [2]

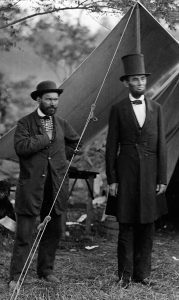

From Clark Street, the omnibus “whirled away” to the St. Louis, Alton and Chicago railroad depot. However, the freedom seekers’ cries had drawn attention to their plight, and a sizable group of African Americans quickly assembled and set out in pursuit, hoping to rescue the Harris family from the grasp of Federal authorities. Yet Webb’s superior, the new U.S. Marshal for the Northern District of Illinois, Joseph Russell Jones, was prepared. Appointed to the post just weeks earlier by President Abraham Lincoln, who was also a personal acquaintance, Jones shocked many Chicagoans by his apparent “zeal” to return the family of freedom seekers to bondage. Waiting at the depot, Jones watched as the family was hustled out of the omnibus and onto a special train he had chartered, which departed at 6:30 a.m. Occurring during the first month of Lincoln’s administration, the case had multiple connections to the 16th president. The train from Chicago carried the Harris family to Springfield, Illinois––Lincoln’s hometown––where another Lincoln acquaintance, U.S. Commissioner Stephen Corneau, promptly remanded the family back into slavery on April 4. While it marked a cruel end to the Harris family’s quest for freedom, for many Northerners the case also raised larger questions about Lincoln’s anti-slavery credentials. [3]

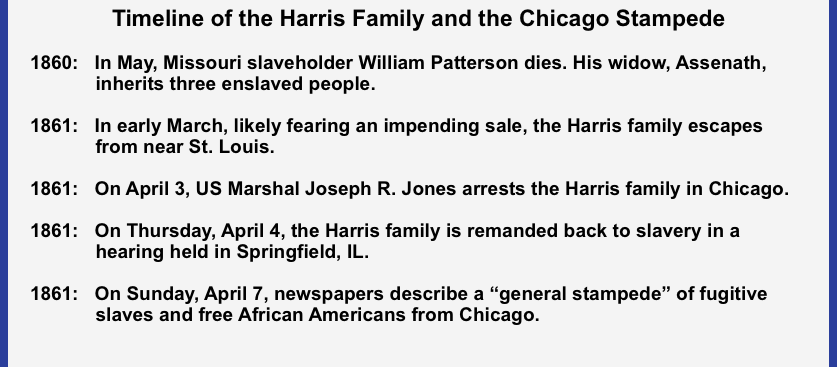

STAMPEDES CONTEXT

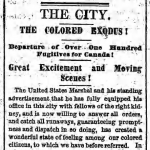

Although newspapers did not call the Harris family’s escape a “stampede,” numerous papers did employ the term when describing the effect the family’s capture had on Chicago’s African American residents. In its initial report on the case, the pro-Republican Chicago Tribune informed readers of a “general stampede” among “the fugitive slaves harbored and residing in this city,” predicting that “within a day or two hundreds of them will have left for Canada.” The Tribune and at least one other paper also referred to the mass departure as a “colored exodus.” [4] Several days later, on April 9, the pro-Democratic Chicago Times ran a column detailing the “colored stampede,” sparked by the seizure of the Harris family. Estimating that several hundred “negro stampeders” had already left the city, the Times‘s anti-black editors expressed hope for “another stampede” to “rid us of the debris of the colored population.” [5]

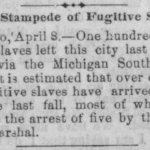

Madison WI State Journal, April 9, 1861 (Newspapers.com)

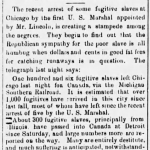

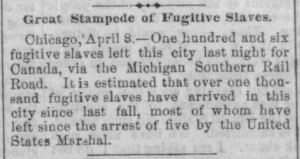

In the following days and weeks, the term “stampede” was used repeatedly by newspapers throughout the North. The Wisconsin State Journal ran the headline, “Great Stampede of Fugitive Slaves,” while a Vermont serial reported a “Large Stampede of Slaves,” and the Washington, D.C.-based National Republican referred to “the stampede of negroes from Chicago.” Crucially, newspapers routinely conflated escaped slaves with free African Americans. A widely reprinted report claimed that “three hundred fugitive slaves, principally from Illinois” had passed through Detroit on their way to Canada, while another dispatch described a group of 106 “fugitive slaves” who reportedly left Chicago on April 7. [6]

MAIN NARRATIVE

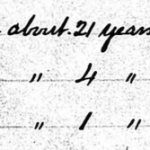

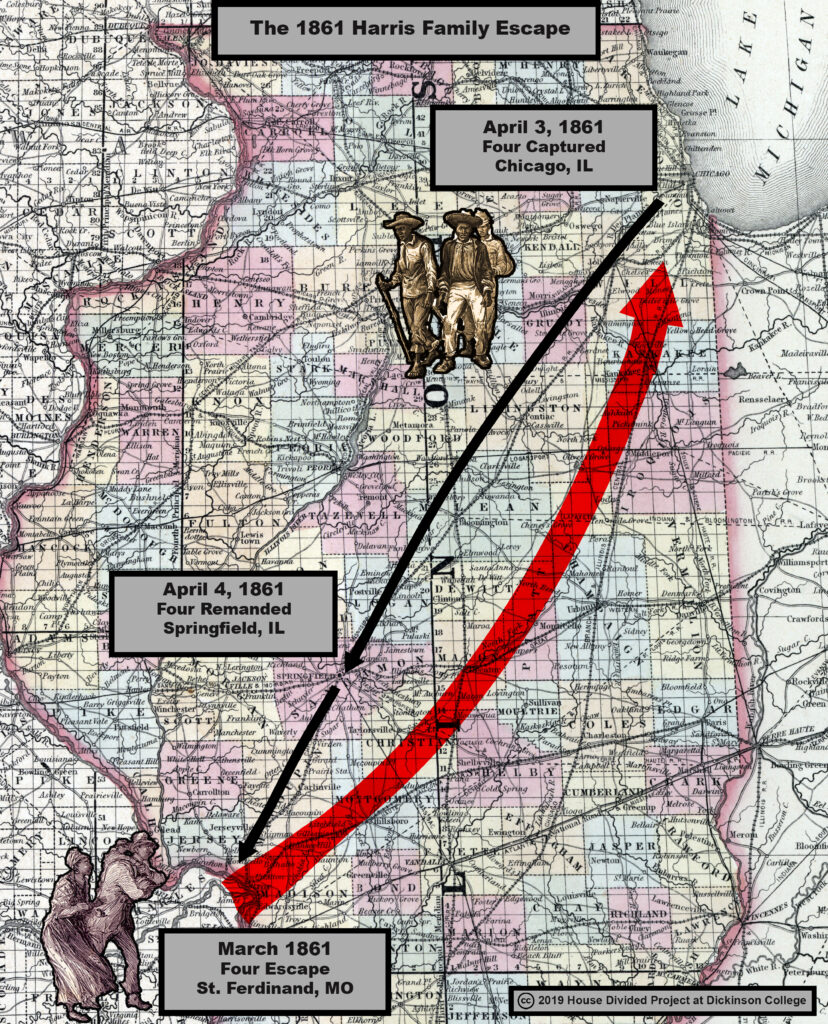

The Harris family had escaped sometime in March 1861 from St. Ferdinand Township, located on the northern outskirts of St. Louis, Missouri. Their bid for freedom may have been inspired by an impending sale, as the aging Missouri slaveholder who claimed Harris’s wife and young children, William Patterson, had died in May 1860 at the age of 77. In his will, Patterson bequeathed to his widow, 69-year-old Assenath Piggott Patterson––the daughter of an early settler in the St. Louis region––”all of my real estate and slaves.” That included three enslaved people, Onesimus Harris’s wife Ann, and their children George and Charles, [7]

Assenath decided to move in with her daughter, Lydia “Liddie” Patterson, and her husband Jacob Veale, a 42-year-old English emigrant. Veale was also one the executors of his father-in-law’s estate, and held one enslaved person––38-year-old Onesimus Harris. While the move may have briefly brought all members of the Harris family under one roof, they knew all too well that estate sales often resulted in the separation of enslaved families. Assenath sought to do just that––at some point in the months following William Patterson’s death, she apparently attempted to sell Ann, George and Charles. [8]

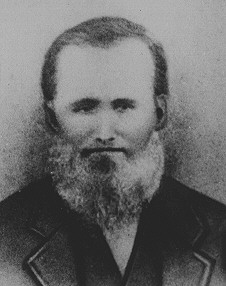

The circumstances of the sale are unknown, but it was likely what prompted the four members of the Harris family to make a run for freedom in early March 1861. They reached Chicago, taking refuge with Ann’s mother, who lived on the third floor of a house at 251 South Clark Street. Yet unbeknownst to the Harris family, Jacob Veale and the Pattersons were in hot pursuit. [9]

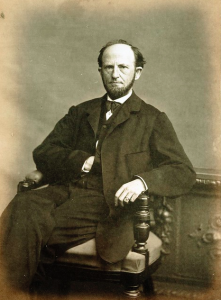

The Missourians headed to Springfield, Illinois, and obtained a warrant of arrest for the four freedom seekers from U.S. Commissioner Stephen A. Corneau, a Federal official tasked with enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. There was a US commissioner in Chicago at the time (Philip A. Hoyne) but neither he, nor any of the leading judicial or political officers of the city were then considered friendly to enforcement of the law. Although Corneau was not necessarily pro-slavery, he was a conservative who abided by the rule of law. He quickly issued his warrant to the new U.S. Marshal for the Northern District of Illinois, Joseph Russell Jones. The 38-year-old Jones was a well-to-do businessman from Galena, Illinois, who had briefly served in the Illinois General Assembly at Springfield, where he had apparently met Abraham Lincoln. When the sitting U.S. Marshal resigned abruptly in early 1861, Lincoln appointed Jones to replace him. [10]

Jones was a Republican appointee, and later claimed that “painful as the duty was,” he felt bound by his oath “to execute a warrant for the arrest of a fugitive slave” as he would “any other process.” Well aware that Chicago’s African American community would resist any attempts to recapture the Harris family, Jones decided to seize the family “early in the morning, before there were many persons on the street.” The new marshal was well aware of the city’s track record on fugitive cases, as black Chicagoans had vigorously resisted the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law ever since its passage. Opposition to the law ran so deep that sometime the tables quickly turned and slave catchers in Chicago could easily find themselves charged with kidnapping. With this in mind, a cautious Jones held the warrants for several days, carefully planning how he would apprehend the Harris family and rush them out of the city to Corneau’s Springfield office before a rescue effort could be launched. [11]

Marshal Jones’s office was located in the Custom House, at the northwest corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets. (Library of Congress)

While Jones set about chartering a private train and hiring an omnibus, he entrusted his 31-year-old deputy, George L. Webb, with organizing a posse to apprehend the freedom seekers. Jones had appointed Webb as his chief deputy just days earlier, and his first task on the job became ensnaring the Harris family. To do so, either Webb or Jones turned to a free African American named Hayes, an express wagon driver who lived nearby on Edina Place. Heading to 251 South Clark Street on April 2, Hayes “insisted [on] lodging at the house” even as residents expressed some unease about their new houseguest. Around 6:00 a.m. the next morning, April 3, Hayes descended the stairs, and unlocked the front door, allowing Deputy Marshal Webb and his posse of six armed men to storm up to the third floor and seize the four freedom seekers. [12]

After the family had been captured and whisked away to Springfield, Hayes became the recipient of the local African American community’s ire. Hayes “got terribly pounded,” before darting into a second-hand clothing store and out the back door, beating a hasty retreat to his nearby home. By mid-morning, a large crowd had encircled his house, pounding on the front door and even “scaling the upper windows with a ladder.” An African American named John Johnson emphatically declared that Hayes “had informed, and he must be got out, dead or alive.” Hayes was ultimately rescued by a contingent of Chicago policemen, who arrived and formed a hollow square around the alleged informant, removing him to the safety of the armory. Seven African Americans (six men and one woman) were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. While the woman (whose name was not recorded) was subsequently released, six black Chicagoans were charged: John Johnson, Franklin Johnson, Charles Johnson, John Barriday, Abraham Thompson and William Lee. Their bail was paid by Allan Pinkerton, the Scottish-born anti-slavery activist and noted detective. In a trial held a week later, John Johnson was represented by abolitionist attorney Chancellor L. Jenks, though he lost the case and was fined $15. [13]

In the meantime, the Harris family was brought before Commissioner Corneau at Springfield. Not only was the hearing held in the new president’s hometown, but also Corneau and Lincoln were neighbors. Their Springfield homes were just three blocks apart, and the two had been friends and political allies since the mid-1850s. Yet in his role as commissioner, the 40-year-old Corneau had already heard two cases involving freedom seekers––one in 1857, and another in 1860––and both times had sided with the slaveholder. In a brief hearing on the morning of April 4, Corneau deemed the evidence provided by Veale and the Pattersons “indisputable,” and promptly remanded the family of four back into slavery. The captured freedom seekers left Springfield on the evening train, bound for St. Louis. [14]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

In the days following the rendition of the Harris family, many Northerners expressed shock and outrage that the four freedom seekers had been seized and returned to slavery under a new Republican administration. One of the city’s leading abolitionist lawyers, L.C.P. Freer, issued a call to “The Old Liberty Guard,” denouncing the new US marshal for “inaugurating a reign of terror among our colored population.” The next day, the Chicago Tribune decried: “We object to a Federal office holder under Abraham Lincoln surpassing in zealous man-hunting all his predecessors in office,” Local residents focused their ire on Marshal Jones, convening a mass meeting and demanding his removal from office. [15]

Yet other Northerners, desperate to avert a looming civil war, hailed Jones’s actions. “It is thus demonstrated that the law for the rendition of fugitive slaves can be executed, and that, too, by a Republican officer, in the city of Chicago,” touted the Chicago Post. “It will convince the people that President Lincoln intends to, and will, support the constitution and execute the laws.” The Post‘s declaration rang true for at least one white Tennessee man, who drew on accounts of the “perfect stampede among the escaped negroes” from Chicago to make the case that “Mr. Lincoln’s Marshals” were enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law, and that slaveholders would fare better by staying in the Union than leaving it. [16]

Yet other Northerners, desperate to avert a looming civil war, hailed Jones’s actions. “It is thus demonstrated that the law for the rendition of fugitive slaves can be executed, and that, too, by a Republican officer, in the city of Chicago,” touted the Chicago Post. “It will convince the people that President Lincoln intends to, and will, support the constitution and execute the laws.” The Post‘s declaration rang true for at least one white Tennessee man, who drew on accounts of the “perfect stampede among the escaped negroes” from Chicago to make the case that “Mr. Lincoln’s Marshals” were enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law, and that slaveholders would fare better by staying in the Union than leaving it. [16]

Meanwhile, some sought to link the case and the “stampede” which followed more directly to Lincoln, accusing the new administration of harboring pro-slavery sentiments. A Buffalo, New York paper reminded readers that it was the arrest of the Harris family, by “the first U.S. Marshal appointed by Mr. Lincoln,” which sparked “a stampede among the negroes,” suggesting that “the Republican sympathy for the poor slave is all humbug when dollars and cents in good fat fees for catching runaways is in question.” Abolitionist George Bassett harangued the new president, holding him personally responsible for “capturing and returning the Harris family” and “the virtual expulsion of 500 fugitive slaves who had been unmolested under previous administrations.” It only served to prove, Bassett maintained, that the Republican party “was pre-eminently a slave-catching party.” [17]

The ultimate fate of the Harris family remains unknown. Ann, George and Charles were appraised at $1000, and apparently sold for $1,589.98. [18] The Federal officer responsible for their capture, Joseph Russell Jones, weathered the controversy over the case and and remained an influential figure, later serving as Minister to Belgium under President Ulysses S. Grant. [19]

The case’s most profound effect may have been the “stampede” of free African Americans and freedom seekers from Chicago. Following the Harris family’s recapture, rumors swirled that “several writs were in officer’s hands” for the apprehension of other freedom seekers, creating “a perfect stampede among the numerous fugitives resident here…. All through last week they left in parties of from four to twelve to fifteen,” detailed the Chicago Tribune. On the evening of Sunday, April 7 alone, over 100 free black residents (or perhaps former fugitive slaves) reportedly crowded into four chartered freight cars of the Michigan Southern Railroad, bound for Detroit and eventually Canada. Paying an average fare of $2 per person, each car was equipped with “a cask of water and substantial provisions, boiled beef, hams, beans, bread and apples.” Most of the participants in the “colored exodus” or “hegira” as the Tribune styled it (referring to Mohammed’s flight from Mecca to Medina), were “young men in their prime, as the class most obviously likely to run the risk of fleeing from slavery.” But there were others, too, whose plight evoked even more pathos, such as one elderly woman so ill that she had to be carried to the train “on a mattrass” [sic] and a “sick child … conveyed in the arms of its father.” As a specially chartered train was preparing to depart the city, the Chicago Tribune reported that many women in the crowd were openly weeping. It was, the antislavery newspaper sadly concluded, “such an exodus as no city in the United States ever saw before.”[20]

Whether or not this stampede was a full-fledged reality, however, is not entirely clear. The partisan newspapers may have exaggerated the rumors and reports of flight. The moment of community-wide panic, even if utterly sincere, may also have subsided rather quickly. We have not yet been able to determine who exactly among the city’s African Americans left Chicago in April 1861, and when, if ever, they may have returned. The only certainty is that despite all of the fears and suspicions of the free black and anti-slavery community raised by the tragic Harris family rendition, the Lincoln Administration never again attempted to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law in Illinois.

To view an interactive map of this stampede, check out our StorymapJS version at Knight Lab

FURTHER READING

The original and most detailed accounts of the case were published by the Chicago Tribune (Newspapers.com). The first, on April 4, 1861, ran under the headline “Onesimus and his Family Sent Back.” The second column from the Tribune was published on April 6, under the provocative title “Man Hunting in Chicago.” Later, Marshal Jones defended his actions with a card published in the April 11, 1861 edition of the Tribune. The pro-Democratic Chicago Times also covered the case in detail, and its account was later reprinted in the New Lisbon, Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle (Newspapers.com) on April 13, 1861.

Another description of the case in the Chicago Post––reprinted in the Baltimore Daily Exchange (Newspapers.com) on April 9––included one crucial new detail: the male freedom seeker was “called Harris, or Johnson.” While it was not uncommon for enslaved people to be identified by more than one name, three of the six black Chicagoans charged with disorderly conduct went by the surname Johnson. Given that the Harris family was known to be staying with maternal relatives, it is certainly possible that these three Johnson men were relatives of the freedom seekers.

Similarly, a story first reported in the Chicago Tribune on April 11, 1861, alleged that a professed abolitionist had duped Ann’s mother, identified as “Mrs. Johnson,” into mortgaging her “little home” to raise $150 in order to fund her daughter’s escape. She handed the money over to this “stranger,” who assured her it would be used to cover “services and expenses in running off” her daughter and enslaved family. When the Harris family arrived in Chicago, purportedly with help from this unidentified white man, he instructed them to stay indoors at the Johnson residence. Meanwhile, he returned to Missouri, alerted Federal officials to the whereabouts of the four freedom seekers, and pocketed a reward offered up by Veale and the Pattersons. The Tribune claimed that this man “is one of a regularly organised gang in St. Louis and Chicago who make a business of running off and then returning slaves, by the shuttle-like process making a very good thing of it. The principal operators are ex-policemen, and policemen high in favor at St. Louis.” The Buffalo, NY Morning Express (Newspapers.com) reprinted the story with a brief editorial comment on April 15, 1861.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

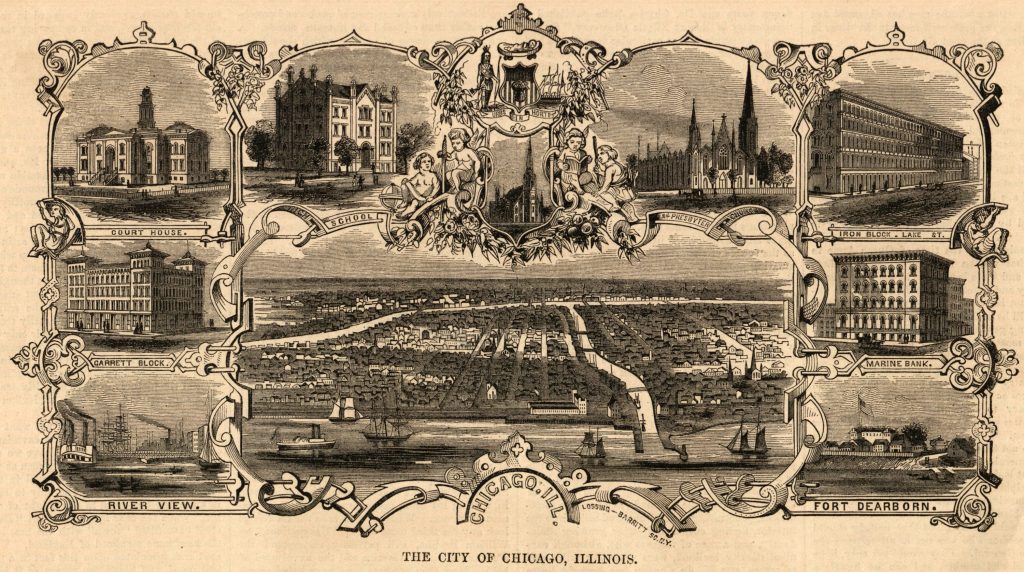

- Chicago, 1856

- Views of Chicago, c. 1859

- Boston Daily Advertiser, April 4, 1861 (Newspapers.com)

- Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1861 (Newspapers.com)

- Madison WI State Journal, April 9, 1861 (Newspapers.com)

- Buffalo NY Daily Republic, April 9 1861 (Newspapers.com)

- Detroit Free Press, April 10, 1861 (Newspapers.com)

- Hyde Park, VT Lamoille Newsdealer, April 12, 1861 (Newspapers.com)

- Jacob Veale holds one enslaved man (likely Harris) in the 1860 U.S. Census (Ancestry)

- Ann, George and Charles are listed in William Patterson’s estate inventory (Ancestry)

- Chicago, 1863

[1] None of the newspaper articles covering the case identified any members of the Harris family by name, except for using “Onesimus” to denote the Harris male. Given that Onesimus is a runaway slave described in Paul 1:10, Onesimus was likely not the male Harris’s real name. (See “Onesimus and his Family Sent Back,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1861). Newspaper accounts were also conflicted over the number of children––some placed it at two, others at three. The names and ages of Ann, George and Charles come from the estate inventory of William Patterson, a Missouri slaveholder whose widow moved into the household of son-in-law Jacob Veale, who held “Onesimus” Harris, shortly before the escape occurred. Given the evidence, it appears likely that Ann, George and Charles were “Onesimus” Harris’s family members, and thus the freedom seekers involved in the case. (See William Patterson, Last Will and Testament, October 16, 1858, and Estate Inventory, August 12, 1861, Missouri, Wills and Probate Records, Ancestry).

[2] “Onesimus and his Family Sent Back,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1861; Chicago Post, quoted in “The Fugitive Slave Case in Chicago,” Milwaukee WI Sentinel, April 5, 1861; “Man Hunting in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1861; “The Arrest of the Harris Family, A Card from U.S. Marshal Jones,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1861; “Five Slaves Carried Off––Africa in a Ferment,” Chicago Times, quoted in New Lisbon, OH Anti-Slavery Bugle, April 13, 1861; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, St. Ferdinand, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry.

[3] “U.S. Marshal,” Chicago Tribune, March 15, 1861; “Onesimus and his Family Sent Back,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1861; “Man Hunting in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1861; “The Arrest of the Harris Family, A Card from U.S. Marshal Jones,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1861; “Five Slaves Carried Off––Africa in a Ferment,” Chicago Times, quoted in New Lisbon, OH Anti-Slavery Bugle, April 13, 1861; Jeffrey N. Lash, A Politician Turned General: The Civil War Career of Stephen Augustus Hurlburt, (Kent, OH and London: Kent State University Press, 2003), 63, [WEB]; Annual Report, For the Year Ending October 31, 1909, (Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1909), 215, [WEB]; “Insured in the Mutual for 60 Years,” Mutual Interests, 35:8 (March 1909): 29, [WEB]; Endorsement of Stephen A. Corneau, appearing in the Illinois Journal on April 26, 1855, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, [WEB].

[4] “Onesimus and his Family Sent Back,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1861; “The Colored Exodus!,” Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1861; “The Colored Exodus from Chicago,” Irasburgh, VT Orleans Standard, April 19, 1861.

[5] “The Colored Stampede,” Chicago Times, April 9, 1861, quoted in Detroit Free Press, April 10, 1861

[6] “Great Stampede of Fugitive Slaves,” Madison Wisconsin State Journal, April 9, 1861; Washington, D.C. National Republican, April 11, 1861; “Large Stampede of Slaves,” Hyde Park, VT Lamoille Newsdealer, April 12, 1861; “Negroes Leaving for Canada,” Buffalo, NY Daily Republic, April 9, 1861; “Fugitives from a Second Bondage,” Pittsfield MA Berkshire County Eagle, April 18, 1861.

[7] 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, St. Ferdinand, St. Louis, MO, Ancestry; William Patterson, Last Will and Testament, October 16, 1858, and Estate Inventory, August 12, 1861, Missouri, Wills and Probate Records, Ancestry; William Patterson, Find A Grave, [WEB]; Assenath Patterson, Find A Grave, [WEB].

[8] “Fugitives Remanded Back,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, April 5, 1861; 1850 U.S. Census, District 82, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1447, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, St. Ferdinand Township, St. Louis County, MO, Family 218, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, St. Ferdinand, St. Louis, MO, Ancestry; Carl William Veale, Patterson-Piggott Family of St. Louis County, Missouri, (Los Angeles: n.p., 1947), 1, [WEB]; William Patterson, Last Will and Testament, October 16, 1858, and Estate Inventory, August 12, 1861, Missouri, Wills and Probate Records, Ancestry; Jacob Veale, Find A Grave, [WEB]; Lydia Rogers Patterson, Find A Grave, [WEB].

[9] “Onesimus and his Family Sent Back,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1861; “Fugitive Slave Excitement in Chicago,” Chicago Post, April 5, 1861, quoted in Baltimore Daily Exchange, April 9, 1861.

[10] “Five Slaves Carried Off––Africa in a Ferment,” Chicago Times, quoted in New Lisbon, OH Anti-Slavery Bugle, April 13, 1861; “Resigned,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1861; “U.S. Marshal,” Chicago Tribune, March 15, 1861; “U.S. Marshal,” Chicago Tribune, March 28, 1861; 1860 U.S. Census, 1st Ward Galena, Jo Daviess County, IL, Family 34, Ancestry; Haplin and Bailey’s Chicago City Directory, for the Year 1861-62, (Chicago: Haplin & Bailey, 1861), 191; Lash, A Politician Turned General, 63; Charter, Constitution By-Laws, Annual Report, for the Year Ending October 31, 1909, (Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1909), 215, [WEB].

[11] “The Arrest of the Harris Family, A Card from U.S. Marshal Jones,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1861; Richard J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 165-167.

[12] “The Fugitive Slave Case in Chicago,” Milwaukee, WI Sentinel, April 5, 1861; “Fugitive Slave Excitement in Chicago,” Chicago Post, April 5, 1861, quoted in Baltimore Daily Exchange, April 9, 1861; “Man Hunting in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1861; “The Arrest of the Harris Family, A Card from U.S. Marshal Jones,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1861; “Five Slaves Carried Off––Africa in a Ferment,” Chicago Times, quoted in New Lisbon, OH Anti-Slavery Bugle, April 13, 1861; Chicago Post, April 4, 1861, quoted in “Great Negro Excitement!,” Boston Liberator, April 26, 1861; “Appointment,” Chicago Tribune, April 1, 1861; House Executive Documents, Index to Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Forty-Fourth Congress, 1875-1876, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1876), 164-165, [WEB]; 1860 U.S. Census, Ward 1, Chicago, Cook County, IL, Family 214, Ancestry; “A Tribute to George L. Webb,” Woodstock, IL Sentinel, September 14, 1905.

[13] “The Sequel to the Harris Case,” Chicago Tribune, April 12, 1861; “Five Slaves Carried Off––Africa in a Ferment,” Chicago Times, quoted in New Lisbon, OH Anti-Slavery Bugle, April 13, 1861; Chicago Post, April 4, 1861, quoted in “Great Negro Excitement!,” Boston Liberator, April 26, 1861; The Chicago Legal News 35(1902-1905):439, [WEB]; Pinkerton later claimed that he had actively aided freedom seekers, writing in the 1880s: “I have assisted in securing safety and freedom for the fugitive slave, no matter at what hour, under what circumstances, or at what cost, the act was to be performed.” Allan Pinkerton, The Spy of the Rebellion; Being a True History of the Spy System of the United States Army During the Late Rebellion, (New York: G.W. Carleton, 1883), xxvi, [WEB].

[14] “Fugitives Remanded Back,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, April 5, 1861; Endorsement of Stephen A. Corneau, appearing in the Illinois Journal on April 26, 1855, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, [WEB]; 1850 U.S. Census, Springfield, Sangamon County, IL, Family 774, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Springfield, Sangamon County, IL, Family 1897, Ancestry; Stephen Augustus Corneau, Find A Grave, [WEB]; Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 1:206, 811; Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, 159-160.

[15] L.C.P. Freer, “To the Old Liberty Guard,” Chicago Tribune, April 5, 1861. “Man Hunting in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1861; Weston A. Goodspeed and Daniel D. Healy, History of Cook County, Illinois, (Chicago: Goodspeed Historical Association, 1909), 1:419, [WEB].

[16] “The Fugitive Slave Case in Chicago,” Milwaukee, WI Sentinel, April 5, 1861; “The Test of Unionism,” Evansville, IN Daily Journal, June 20, 1861, [WEB].

[17] “Negroes Leaving for Canada,” Buffalo, NY Daily Republic, April 9, 1861; George W. Bassett, A Discourse on the Wickedness and Folly of the Present War, (n.p., 1861), 13, [WEB].

[18] William Patterson, Estate Inventory, August 12, 1861, Missouri, Wills and Probate Records, Ancestry.

[19] Joseph Russell Jones to Abraham Lincoln, January 7, 1863, Series 1, General Correspondence, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, [WEB]; Charter, Constitution By-Laws, Annual Report, for the Year Ending October 31, 1909, 215, [WEB].

[20] “Departure of Fugitive Slaves for Canada,” New York Times, April 9, 1861; “The Colored Exodus!” Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1861.