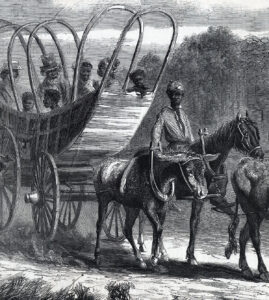

Fugitive slaves entering Union lines, July 1864. (House Divided Project)

By 1862, white Missourians were deeply unsettled. The state’s enslaved population, a key source of labor, was rapidly disappearing. “All the negroes in this country will run off,” Missouri farmer Willard Mendenhall scribbled in his diary in late October 1862. “They go in droves every night.” [1]

Although Mendenhall uses a different word, he was referring to slave stampedes, or group escapes, which by 1862 were eroding slavery throughout much of the border South. Mendenhall’s account is one of many featured in Diane Mutti Burke’s recent book on Missouri slavery, On Slavery’s Border (2010). In her book, Mutti Burke addresses the perception that border state bondage was somehow “milder” than that experienced in the Deep South. On average, Missouri slaveholders owned smaller farms and fewer enslaved people than enslavers in other slave states. As a result, Missouri slavery assumed a more “intimate” nature, in which slaveholders and enslaved people interacted more frequently. Citing these factors, many Missourians compared themselves favorably to plantation slaveholders further south. However, Mutti Burke dismisses their claims as “more rhetorical” than realistic. The increased interactions between slaveholder and slave, she argues, “more often than not… fostered enmity rather than empathy,” and created more opportunities for physical, mental and verbal abuse. [2]

The actual term slave stampede appears just once in Mutti Burke’s tome, in reference to a “veritable ‘stampede’ of slaves leaving their owners” by the summer of 1863. However, the concept of group escapes, particularly those triggered by the presence of nearby Union forces, appears repeatedly. She notes that “slave men, women, and children flocked to the nearest military encampments seeking their freedom.” She also recounts a number of escaped slaves who returned to their plantations or farms, sometimes with the aid of Union soldiers, to free other family members. Drawing on Mendenhall’s diary, she recounts the story of one enslaved man, named Bob, who returned to a Saline County farm with “a squad of white men… and took his wife and two children away,” along with two of his slaveholder’s horses. [3]

“The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri,” an article referencing the group escape of Lewis County slaves, that ended in bloodshed. (North American and United States Gazette, November 22, 1849)

While she discusses group escapes primarily in the context of the Civil War, Mutti Burke also references one notable antebellum stampede. In November 1849, a group of over 30 Lewis County slaves armed themselves and headed northward, but the escape attempt ended in a clash with slaveholders, leaving one enslaved man dead. However, Mutti Burke treats the incident more as an attempted slave insurrection, and does not use the word stampede, although period newspapers referred to it as such. She does describe how the 1849 episode led to changes in Missouri state law that were designed to clamp down on the possibility of slave escapes.[4]

She mentions another possible pre-war stampede, a “large group of runaways” who escaped into the Kansas Territory in January 1859, assisted by New York abolitionist Dr. John Doy, who had been influenced by a similar escape undertaken by John Brown. However, Platte County slaveholders tracked down the group and recaptured them, sending Doy to prison for a brief period of time before he was rescued from custody by free soil forces from Kansas. [5] While Mutti Burke’s book is an invaluable resource on Missouri slavery, more work still remains to better understand the frequency, locations and ultimate results of slave stampedes.

[1] Willard Hall Mendenhall Diary entry, October 30, 1862, in Missouri Ordeal 1862-1864: Diaries of Willard Hall Mendenhall, ed. by Margaret Mendenhall Frazier, (Newhall, CA: Carl Boyer, 1985), 84, [WEB].

[2] Diane Mutti Burke, On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small-Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 125, 143, 171-172, 196-197, 305-306.

[3] Burke, On Slavery’s Border, 283-284; Mendenhall Diary entry, November 7, 1862, in Missouri Ordeal, 86, [WEB].

[4] Burke, On Slavery’s Border, 186; “The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri,” Philadelphia North American and United States Gazette, November 22, 1849.

[5] Burke, On Slavery’s Border, 176-177. See also Kansas Memory.