In December 1858 while hiding out in the Kansas Territory, John Brown, a prominent abolitionist and leader of a free soil militia group, received an important request from Jim Daniels, an enslaved man in Missouri. Daniels was fearful after learning that his family was to be sold and asked for Brown’s help in freeing them.

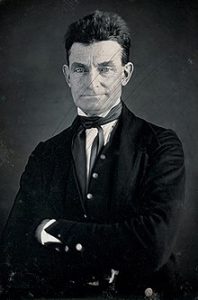

John Brown courtesy John Brown (abolitionist) wikipedia

Brown and his armed men soon traveled into Missouri, freed the five members of Daniel’s family and five more enslaved people from a neighboring plantation, while another group of men freed a woman from a nearby farm and killed her former slaveholder. Then the entire party headed back to Kansas together, hiding out for a month, where a baby was born and christened John Brown.

In January 1859, this group of eleven, and their newest addition, headed North towards Nebraska, and freedom, under the armed protection of Brown and his men. In 82 days, this veritable “slave stampede” crossed the Missouri River, worked their way east with help from the underground railroad network in Iowa, and travelled to Chicago by train. After traveling nearly 1,500 miles, on March 12, 1859, they arrived in Detroit, and crossed the Detroit River by ferry to Windsor, Canada. [1]

Fergus M. Bordewich’s work Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (2005) is filled with such tales of thrilling and improbable escapes to freedom. The book details the people, both black and white, behind the Underground Railroad, one of America’s most mystifying legends. Historians have hailed the work as a significant contribution to the literature. Stanley Harrold, for one, writes that Bound for Canaan is “the first truly comprehensive treatment of the Underground Railroad in over a century, and by far the best.”[2]

Bordewich details dozens of stories of mass escapes even though he does not use the term “stampede” to describe any of them. Perhaps that is because several of the escapes he describes involved extended families. But others involved strangers, working together, almost in acts of collective insurrection. For instance, eighteen enslaved men stole a ship from the harbor of Northampton County, Virginia and sailed it to New York City [3].

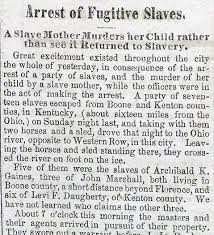

News clipping of the “Margaret Garner Incident” courtesy of Cincinnati History Library and Archive.

The Garners, a family of eight fleeing slavery in Kentucky in 1856, are an important example of a family stampede. Their story ended in tragedy when they were recaptured in Cincinnati. Instead of seeing her children returned to slavery, Margaret Garner killed her young daughter. Abolitionists used the event to highlight the horrors of slavery [4].

Other intriguing references to group escapes are less detailed. Bordewich notes massive numbers of enslaved people making a run to Canada in the days leading up to the Civil War. He writes that in April 1861, the “Detroit Daily Advertiser reported that 300 fugitives had passed through…[Detroit] en route to Canada within the previous few days, 190 of them on April 8 alone,”[5]. Despite all of these references to large groups or extended families escaping together, Bordewich does not use the term “slave stampedes,” nor even “group” or “mass” escape. He doesn’t seem to consider this as a separate category of analysis. In addition for the particular interests of this project, Bordewich’s research is national in scope, meaning references to Missouri are quite limited. Yet overall, Bound for Canaan allows for a greater understanding of the inner workings of the Underground Railroad and paints a detailed portrait of the people behind the scenes. Although, the words “slave stampede” are not actually used, it brings forth untold stories of groups of enslaved freedom coming together in ways that deserve careful attention from this project.

[1] Fergus M. Bordewich. Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York: HaperCollins Publishers Inc, 2005), 419-20. NOTE: Later editions of Bordewich’s book use a different subtitle: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement.”

[2] Stanley Harrold, review of Bound for Canaan by Fergus M. Bordewich, Civil War History 52 (Sept. 2006): 310-12.

[3] Bordewich, 272

[4] Bordewich, 401- 405

[5] Bordewich, 429