Interactive Essay

"William Elisha Stoker: A Texas Farmer’s Civil War"

by Don Sailer

by Don Sailer

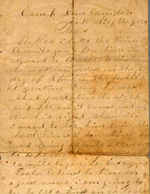

The National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania holds original manuscripts from hundreds of Civil War soldiers, including Private William Elisha Stoker, a young father from Texas who fought for the Confederate army.

We have no photograph of Private Stoker, but his collection of 30 letters written between August 1862 and May 1864 offers as vivid a snapshot as any of wartime life for a young, scared, soldier and a lonely husband and father. Stoker hated that the war kept him away from his wife Elizabeth or Betty and their young daughter Priscilla, both of whom he missed deeply. “When I reflect back upon the happy days we have spent together at that sweet little home and then think where I am now it nearley makes my heart sink with dismay,” he wrote.

"William Elisha Stoker: A Texas Farmer’s Civil War" p. 2

Stoker was a member of General John Walker’s Texas Division, which historian Richard Lowe considers “the single most formidable Confederate fighting unit” in the trans-Mississippi theatre. Historians know little about Stoker’s life before his military service began in 1862. Born in Alabama in 1837, he moved with his extended family to Troup County, Georgia at some point before 1850. Then Brother Elisha, as his step-brothers called him, moved to east Texas, married a young woman named Elizabeth, and established a farm outside of Coffeeville in Upshur County.

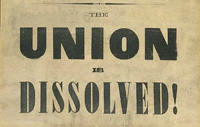

The young couple had at least one daughter, Priscilla, before Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election and southern states seceded from the Union. The Stokers did not live on a plantation and were not active in politics, but they owned two slaves. The conflict over slavery’s future was a conflict about their way of life.

"William Elisha Stoker: A Texas Farmer’s Civil War" p. 3

Yet it appears that William Elisha Stoker was not among the 25,000 Texans who volunteered for service as the war started. The Confederate government authorized a draft in February 1862 and Stoker entered Company H of the 18th Texas Infantry in May. His letters suggest that he was conscripted into service. Stoker’s Texas company marched to Arkansas over the summer of 1862, arriving by September, but they did not actually receive combat rifles until November. While stuck in camp, Stoker’s thoughts turned repeatedly to his family in east Texas. He desperately wanted to hear from his young daughter Priscilla:

“When you write fill a sheet every time if you can and cant think of nothing get Priscilla to say some thing and write it. You wrote that she was as smart and as pretty as ever. I wish I could see you and her. I am afraid you and her your features I will forget. I have wished lots of times that I had your likeliness taken and brought with me.”

Stoker also loved and missed his wife. Occasionally he included a poem –

“My pen is bad my ink is pail

My love to you will never fail.”

"William Elisha Stoker: A Texas Farmer’s Civil War" p. 4

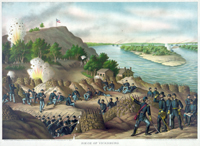

For thirteen months, Stoker’s military experience consisted mostly of marching. But that changed dramatically in early June 1863. Confederate generals decided to employ Walker’s Texas Division as part of a desperate effort to stop the Union campaign to seize Vicksburg, the last remaining Rebel stronghold on the Mississippi. Yet the result was a major engagement at Milliken’s Bend and then a series of smaller skirmishes across northern Louisiana –none of which succeeded in preventing the Union takeover of the Mississippi. Merely a young private, Stoker didn’t fully appreciate the larger strategic picture, but he knew the situation was bad for his side. He told his wife Betty that even General Walker had admitted they had “done well to come out with any men at all.”

Whenever William Stoker wrote home, he did not hide the harsh reality of army life. He claimed he only wanted “to let [Elizabeth] know how soldiers had to live.” One issue that the young farmer mentioned repeatedly in his letters was the lack of good food. “Plant lots of vegetables,” he instructed Betty, claiming that once he returned home his family would “see some of the powerfulest eating” because he was “nearley perrished out for something good to eat.”

"William Elisha Stoker: A Texas Farmer’s Civil War" p. 5

In addition, Stoker’s assessment of the medical care that he and his colleagues received was harshly critical.

“We are all getting verry much dissatisfide. Up hear there is so much sickness and so many dyeing. They just dye all the time. The Doctors is out of medisens and if they had a waggon load it wouldent do any good for they are so lazy they want get up when they are setting down to give a sick man a dose of medisen.”

Both the grueling army life and his loneliness contributed to Stoker’s belief that the war simply had to end. One year into his military service, the Texas farmer concluded –

“Times gets harder with the soldiers Ive got so I just wish this confederacy was toar all to smash and turned bottom [up?].”

Stoker was especially tough on the officers in his unit. Enlisted men, he reported, had “give up all hopes of us gaining our independence,” but he told Betty that the officers never would admit defeat since then “[their] big pay would stop.”

"William Elisha Stoker: A Texas Farmer’s Civil War" p. 6

Stoker’s involvement in the war ended in late spring 1864, following the Battle of Jenkins Ferry, which took place on the banks of the Saline River in Grant county, Arkansas. This battle was part of the Red River campaign, a failed effort by the Union military to end Confederate resistance west of the Mississippi.

Stoker’s half brother Thomas McKissack informed Elizabeth Stoker in a short letter dated May 7, 1864 that her husband had been shot in the chest during the battle. Thomas was hopeful, or at least appeared to be in the note. “I think he will get over it…[and] he said he would come home as quick as he could,” he wrote gently. William Stoker, however, never returned home to his wife and daughter. He was one of the nation’s more than 620,000 casualties of war. What he left his family, however, was a rich testimony about the hardships of that conflict and the sacrifices of a generation of Americans who fought with each other so bitterly over the meaning of their great national experiment.