The Roadblock and Passion of Partisanship

By Nick Rickert

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. held “the white moderate” responsible for much of the “great stumbling block” on the path towards racial freedom and justice. King and other figures who struggled for justice might argue today that this enabling of injustice continues. Partisan divisions from both the past and present generate doubt about the effectiveness of political parties to promote change. George Washington cited factionalism as degrading to the Union, emphasizing their favoring of maintaining power over one another rather than having the good of the people in mind.[2] Such turmoil was witnessed before and during the Civil War Era.

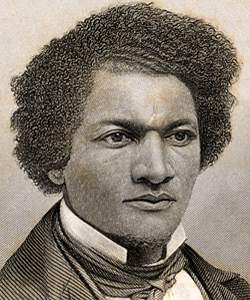

President Abraham Lincoln faced intense scrutiny from the Democratic Party and even members of his own Republican Party because of his anti-slavery position. Frederick Douglass had moved in and out of different political factions as one way to fight for radical ideas of abolition and racial equality, drawing constant bipartisan criticism along the way. Both regarded the war effort as necessary to abolish slavery for the Union’s future; yet their conduct and beliefs surrounding political parties reflected different approaches to fight for justice, justice having separate definitions for each. Lincoln prioritized a broad political coalition with an emphasis on unity to pursue antislavery politics gradually. Douglass prioritized being a part of a coalition that was committed to abolishing slavery but changed allegiances in the short term due to circumstance.

Douglass’s involvement in politics shifted dramatically throughout his life, having rejected it entirely early on as a free man. Although his interest in reading and discussing politics had only grown from even before he escaped for freedom 1838, his involvements in factions before 1848 were only with apolitical ones. Fascinated by the abolitionist messages of William Lloyd Garrison, he dismissed political institutions that Garrisonians claimed upheld a constitution that was proslavery.[3] Rather than continuing to combat slavery only through groups like the New England Anti-Slavery Society that exclusively addressed the public through moral suasion, Douglass gradually dissented from Garrison partially by displaying interest in the potential change that antislavery politics could achieve. In addition to his political activity beginning with the Liberty, Free Soil, and Free Democrat Parties, Douglass continued to persuade his readers and listeners with abolition but also strayed from Garrisonian pacifism. In response to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act he “urged America’s slaves and their allies to ‘reach the slaveholders’ conscience through his fear of personal danger.…”’[4] As Douglass’s antislavery strategy focused less on his initial idealism and more on practical means, he became more deliberate about choosing which factions he engaged in. Despite Douglass’s coming to terms with some kind gradual work with the necessity of building a political coalition, he never compromised afterwards on his stance that American slavery was an evil that needed to be eradicated to save a Union that promised liberty for all.

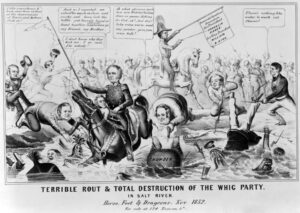

As Douglass developed his initial antislavery beliefs under Garrison, in 1852 Lincoln had credited part of his own stances on the matter to fellow Whig statesman Henry Clay.[5] Lincoln’s reasons for working as a Whig politician, however, did not resemble Douglass’s political motivations. Deeply influenced by his disadvantaged upbringing, Lincoln held economic health and mobility across the nation as a vital issue. Lincoln placed his political faith in Clay’s “American System.”[6] Lincoln knew that the country’s founding principles should guarantee every man and woman the opportunity to improve their life through labor, which was threatened by slavery to him just as much as the US’s morality was if not more. Unlike Douglass, Lincoln was a politician and did not condemn the South. Firm on his Whig principles that began to lose cohesion within the party, Lincoln saw weakening outside support and remained loyal to the Whigs until 1852 with aspirations that a final compromise on slavery’s expansion would finally end the slavery debate. While Lincoln was not an active member of any party, he declared in 1854 that the nation had the “duty to wait” while God halted the expansion of slavery.[7] Meanwhile up North, Douglass remained politically active by trying to grow influence partly through factionalism, fighting to end the spread of slavery to the West as one step towards abolition and equality.

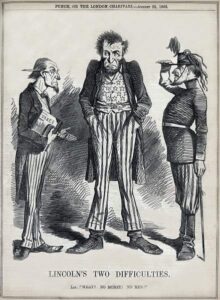

Both Douglass and Lincoln understood the immeasurable value of having a wide range of appeals of a coalition with their respective antislavery stances. Nevertheless, upon his return to politics Lincoln would constantly compromise under the conditions that the extension of Slavery was immoral.[8] Lincoln easily forgave differences that Douglass would not necessarily have done by 1855 to establish an antislavery coalition, especially one with such a moderate position like the Republican Party. Instead of fusing together groups by considerably watering down personal beliefs, Douglass expanded his base of abolitionists somewhat through widening the appeal towards oppressed groups whose struggle for freedom and justice were similar in his mind. This included women’s rights efforts led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott who were fundamental in the drafting of the “Declaration of Sentiments” in 1848 in Seneca Falls, where Douglass was the only Black man to address the audience. [9] Regardless, neither of the men had reason to be optimistic that they could form a coalition strong enough to peacefully restrict the expansion of slavery. Lincoln conceded to the Anti-Nebraska Democrats in the state legislature in 1855 to avoid a stalemate in electing a senator that would have “let the whole political result go to ruin.”[10] Lincoln persisted with his Republican party. In an attempt to resist proslavery Democrats like Stephen Douglas, Lincoln mitigated the ever present ill of partisanship by organizing his coalition around the single principle that there is a dichotomy of right and wrong. Slavery belongs to the latter.

Lincoln’s stress on his antislavery message over “secondary issues” demonstrated focus for the Republicans to help prepare for future campaigns.[11]Lincoln knew that fierce antislavery legislation required cultivation of public opinion through his leadership of the Republican Party because “the man who is of neither party is not –cannot be, of any consequence.”[12] In contrast to Lincoln’s intent to evoke patriotic principles to fight slavery, Douglass with his passion would not yet enter the mainstream antislavery politics of the Republicans. Douglass met instead with violent men like John Brown of the Radical Abolitionist Party in 1855 and celebrated him as an abolitionist hero after the bloody raid at Harper’s Ferry.[13] Additionally, Douglass bolstered his antislavery strategies by also promoting a kind of sectionalism for Black Americans that sought to racially unite through common responsibility.[14] Douglass altered his political relationships and actions to adapt to circumstances of oppression in unexpected ways at times, still his criticism of the Republican Party was consistent with his values in 1860. Douglass became deeply disappointed in the compromise of the Republicans and dismissed the idea of their cautiousness as a panacea for the profound injustice of slavery . Once the years of brutality delivered by the Civil War affirmed to Douglass that the Republican Party was the coalition that would abolish slavery, he was prepared to fully support President Lincoln. The President’s Gettysburg Address reignited the necessity of abolition for the nation and instilled him as the face of political justice. Douglass rebuked proslavery Democrats and compromising Republicans that undermined the purpose of the war[15], although he ultimately became a Republican in 1864 largely because of his respect for President Lincoln. His appreciation would only grow until his death in 1895.

Perhaps Dr. King would have recognized Lincoln as the “white moderate” that prolonged overdue justice. President Lincoln certainly displayed hesitation and compromise in political decisions, but he freely admitted to this critique for slow change. Both the President and Dr. King recognized the necessity to have public support to make progress in a proper democracy, but whether the conflicts surrounding political parties required slower action must be put in the context of the time to understand change. Nevertheless, Dr. King’s allegiance to groups like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and that of President Lincoln’s to the Republican Party illustrates the effectiveness of gradual efforts fueled by commitment. Dr. King was no doubt inspired by Douglass’s orations and diversity of efforts in the name of equality but would in a way also likely refute his tendency towards what he deemed “violent tension” that widened divisions. In the case of this radical and this Republican, not only had their personal dialogues improved mutual understanding but their political factions as well. Lincoln fundamentally agreed multiple abolition parties while Douglass understood that the Republicans promoted the best possible future of the country during the Civil War. Civil political discourse could help overcome the competition between factions that President Washington had warned as disastrous for the Union, but not without a core set of principles to define figures and parties.

[1] Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail. Month and date1963. Found in the African Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania. [find here]

[2] George Washington, “Farewell Address,” September 19,1796. Found in the Library of Congress. [find here]

[3] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (Norton, 2007), 8-9.

[4] Andrew Delbanco, The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War (Penguin, 2019), 196).

[5] Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, 45.

[6] Ibid, 45.

[7] RW, p. 61. Found in Oakes, The Radical Republican, 53.

[8] Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, 54.

[9] Wagner Lecture. July 15, 2021. Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[10] Abrahan Lincoln, February 9, 1855. Found in “Man of Consequence” by Matthew Pinsker.

[11] Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, 56.

[12] Abraham Lincoln, July 6, 1852. Found in “Man of Consequence” by Matthew Pinsker.

[13] Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, 97-99.

[14] Ibid, 114.

[15] Ibid, 234.