By the end of spring semester 2019, we will submit a report to the President’s Commission on Inclusivity that will summarize our investigation into the college’s longstanding ties to both slavery and antislavery. We will also offer an analysis of how the college and the community of Carlisle have remembered –or have chosen to ignore– some of these subjects over the years and suggest how they might better commemorate them in the future.

On this page, we are asking members of our community to consider two questions that will be essential to this forthcoming report:

- Should the college consider renaming any buildings or removing any memorials that commemorate Dickinsonian slaveholders?

- Should the college consider adding memorials that commemorate the contributions of enslaved people or free African Americans who worked here?

This entire website and the physical Dickinson & Slavery exhibit at the House Divided Project studio (61 N. West Street) both serve to provide context for these profound questions, but we will provide a concise summary of these issues below. At the bottom of the page, readers will then be able to post their own comments, or if they choose, they can email them directly to hdivided@dickinson.edu. Selections from these comments will be incorporated into the report presented in 2019 to the President’s Commission on Inclusivity.

Should the college consider renaming any buildings or removing any memorials that commemorate Dickinsonian slaveholders?

There are dozens of buildings and memorials of various types across the Dickinson campus named after a wide range of individuals from the institution’s past. We have identified at least seven former slaveholders who are currently being honored with a named buildings or sections of the campus, but they can probably be separated into two distinct categories:

Slaveholders who freed their own slaves and / or later came to oppose slavery:

- James Buchanan

- John Dickinson

- Benjamin Rush

- James Wilson

Dickinson, Rush and Wilson were all important Founding Fathers of the nation as well as the college. John Dickinson, our namesake, was the largest slaveholder of this trio, but he memorably spoke out against slavery at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, warning that they were all risking the appearance of hypocrisy by establishing a nation around “this new principle” of “a Right to govern Freemen on a power derived from Slaves.” Despite owning his own slave, whom he emancipated quite slowly, Benjamin Rush, the true founder of our college, agreed with Dickinson and urged the abolition of slavery in America. James Buchanan was never a slaveholder, but he did help arrange for legal freedom coupled with prospective indentured servitude for two enslaved Virginians in 1835 (a mother and her daughter). Yet the daughter died almost immediately and then the mother, Daphne Cook, ran away. If they had lived and remained in his household, it’s possible these women would have served Buchanan for years without wages (to pay off their “debt” to him). (NOTE –this information has only recently been updated in 2021 and corrects the previous historical record). Regardless, as president, Buchanan became notorious for his “doughface” or proslavery leanings.

Slaveholders (or pro-slavery figures) who never renounced slaveholding:

- John Armstrong

- Thomas Cooper

- John Montgomery

John Armstrong was a leading though sometimes-controversial military figure during the colonial and revolutionary eras. He was also an early college trustee who owned slaves. John Montgomery was perhaps the most active of the early college trustees, but he was not merely an unrepentant slaveholder, he bought and sold human beings as well. But perhaps the most inexplicable commemoration of a slaveholder on our campus belongs to Thomas Cooper, the namesake of Cooper Hall. Cooper briefly served as a faculty member at Dickinson in the early nineteenth century –and he was a great scientist– but he also became quite controversial later in his career as pro-slavery intellectual in South Carolina.

Should the college consider adding memorials to commemorate the contributions by enslaved people or free African Americans who worked here?

There were dozens of African Americans who lived and worked around the Dickinson College campus during the nineteenth century. Even earlier there were also some enslaved people employed to help construct the first buildings on campus. But out of these figures, only one, a former slave named Noah Pinkney, has ever been recognized by the college with an official commemoration ( a plaque near East College gate). Yet Pinkney is only one of perhaps three central black figures from the college’s nineteenth-century past:

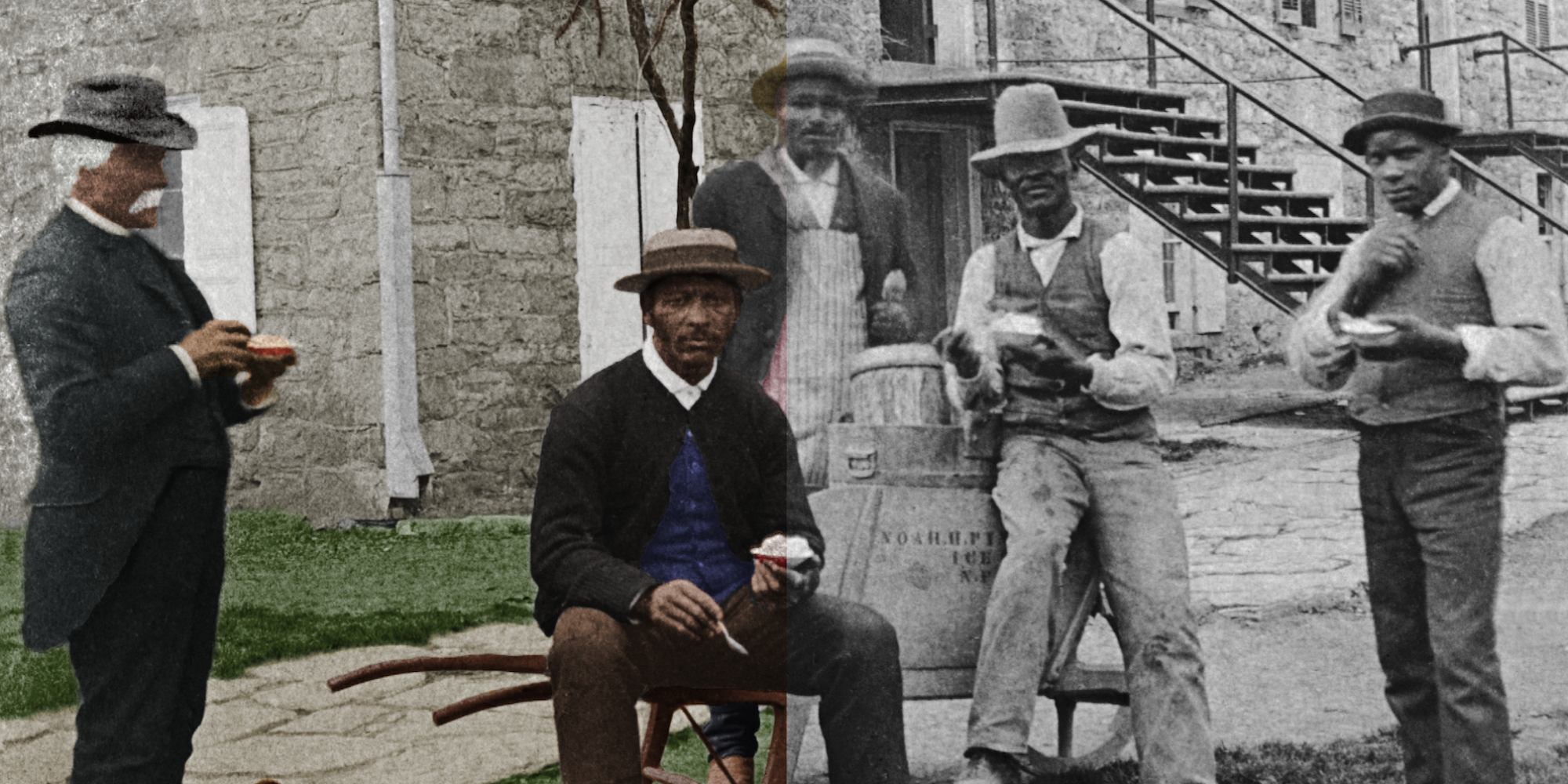

Noah Pinkney escaped from slavery in Maryland and later was present with the Union army at Appomattox. He became such an icon at Dickinson after the Civil War that the college erected a plaque in his honor during the 1950s. Pinkney and his wife Carrie sold pretzels, sandwiches, ice cream and other treats to generations of students.

Henry W. Spradley was a former enslaved stonemason from Virginia, who escaped during the Civil War, fought in the Union army, and later became the most beloved janitor at Dickinson. He participated in the groundbreaking ceremonies for Denny Hall. The school even closed for a day in his honor following his death in 1897.

Robert C. Young was the longest-serving employee of Dickinson before the 21st-century. Born enslaved in Virginia, Young began his work on campus as a household servant, became a janitor and then eventually head of campus security. He worked at Dickinson for over 40 years. In 1886, he also fought to get his eldest son admitted to the college.