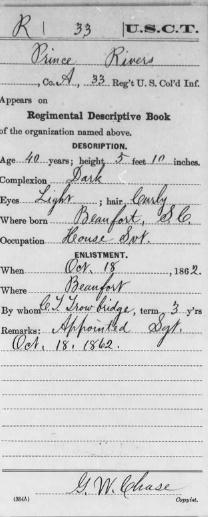

Prince Rivers was born enslaved in South Carolina but became famous as a free man and soldier on January 1, 1863. You can read more about his role in celebrating Emancipation Day in Beaufort, South Carolina as color sergeant in the First South Carolina Volunteers here, but this post contains additional biographical information about this important but still largely obscure nineteenth-century American.

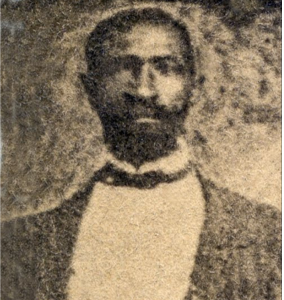

Prince Rivers (c. 1822-1887)

Congressional confiscation acts (August 6, 1861 and July 17, 1861) effectively freed thousands of slaves, including one remarkable black soldier in the Union army. Prince Rivers, a former slave who became the color bearer of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, received the following document from General David Hunter on August 1, 1862:

Headquarters, Department of the South

Port Royal, S.C. August 1st, 1862

“The bearer, Prince Rivers, a sergeant in First Regiment S.C. Volunteers, late claimed as a slave, having been employed in hostility to the United States, is hereby agreeably to the law of 6th of August, 1861, declared free for ever. His wife and children are also free.”

D.Hunter

Maj.-Gen. Commanding

[Reprinted in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 30, 1862]

Hunter’s decision to attempt to use congressional confiscation policy to “free” Rivers and hundreds of other black men who had served in his black regiment was the result of a bitter controversy over whether or not he was properly authorized to employ black troops. Historian Daniel W. Crofts deftly explains the firestorm over Hunter’s early (and stillborn) experiment in raising black troops in a recent post for the “Disunion” series by the New York Times.

Rivers, however, never regretted his unpaid service in “Hunter’s Regiment.” On November 4, 1863, Rivers told a public gathering in Beaufort:

“Now we sogers are men –men de first time in our lives. Now we can look our old masters in the face. They used to sell us and whip us, and we did not dare say one word. Now we ain’t afraid, if they meet us, to run the bayonet through them.”

[Source: Leon Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long, p. 64; Report of the Proceedings of a Meeting Held at Concert Hall, Philadelphia, on Tuesday Evening, November 3, 1863, To Take Into Consideration The Condition of the Freed People of the South (Philadelphia, 1863), 22. Full text of Rivers’s speech, delivered in Beaufort on November 4, 1863 and as originally reported on November 9th by the New York Tribune, can be found at the Internet Archive here.

Rivers had been a house servant and coachman for his master, Henry Middleton Stuart, Sr. (1803-1872) or H.M. Stuart. The mistress at the Oak Point or Pages Point plantation (located in the Beaufort District by the Coosaw River) was Ann Hutson Means Stuart (1808-1862). The Stuart’s children included Ann (1827-1905), Isabel (1831-1873), and Henry Jr. (or Hal) (1835-1915) who served as an officer (eventually captain) for the Beaufort Artillery Battery and later became a leading medical doctor in Beaufort. [Genealogy information on Stuarts comes from Frances Wallace Taylor, Catherine Taylor Matthews, and J. Tracy Powers, eds., The Leverett Letters: Correspondence of a South Carolina Family, 1851-1868 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000). After the war, Rivers tried to exact some measure of revenge by obtaining part of the Stuart plantation. A letter he wrote to Union general Rufus Saxton in 1865 made the request:

Morris Island, South Carolina November 26, 1865

General,

I have the honor to ask for a understanding. I was told that the Government has given Land to Soldiers. If this land were given will [it] be just for the time being or will [it] be hereafter held by the Soldiers? I would like very much to know if any Part of the Mainland. If so I would like to get a piece on Mr. H.M. Stuart plantation, Oak Point, near Coosaw River.

Prince Rivers, Color and Provost Sergeant

[Source: Dorothy Sterling, ed., The Trouble They Seen: The Story of Reconstruction in the Words of African Americans (New York: Doubleday, 1976), 37]

Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who had commanded the First South Carolina Volunteers, wrote a glowing profile of his men and Sergeant Rivers for the Liberator on February 24, 1865. Higginson claimed, “There is not a white officer in this regiment who has more administrative ability” than Prince Rivers, adding, “No anti-slavery novel has described a man of such marked ability.” About his color bearer, Higginson concluded, “if there should ever be a black monarchy in South Carolina, he will be its king.”

Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who had commanded the First South Carolina Volunteers, wrote a glowing profile of his men and Sergeant Rivers for the Liberator on February 24, 1865. Higginson claimed, “There is not a white officer in this regiment who has more administrative ability” than Prince Rivers, adding, “No anti-slavery novel has described a man of such marked ability.” About his color bearer, Higginson concluded, “if there should ever be a black monarchy in South Carolina, he will be its king.”

Rivers actually did become an important political leader in South Carolina during Reconstruction and played an especially pivotal role as a judge during the 1876 Hamburg Massacre. His activities during the post-war period attracted a great deal of attention, including this hostile portrait and this dismissive story from the Atlanta Constitution. The story of Prince Rivers thus sadly embodies the glorious hope and the bitter betrayal of emancipation’s promise. His triumphal moment on January 1, 1863 captured by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper became his tragic inability as a beleaguered black Trial Justice to stave off violence in Hamburg, South Carolina during the 1876 campaign.

The Anderson (SC) Intelligencer carried a terse death notice for Rivers on April 28, 1887: “Prince Rivers, who was a leader among the negroes in radical times and prominent in the Hamburg riots, died in Aiken a few days ago.” The Watchman and Southron in Sumter, South Carolina added some additional details a few days later, noting that Prince Rivers had “died at his home in Aiken on Sunday, 10th inst. of Bright’s disease of the kidneys, in the sixty-fifth year of his age” (May 4, 1887). NOTE –Both newspapers are available freely online from Chronicling America project sponsored by the Library of Congress and National Endowment for the Humanities.

To read more about Prince Rivers, go to our exhibit at Google Arts & Culture, entitled, “The Prince of Emancipation.”

As a “serious” effort in historical research, I have studied Prince Rivers. What is the real truth on Rivers? Have you leads? They are welcome.

Julian L. Mims III, PhD

114 Summer Fun Road

Gilbert, SC 29054

As a descendant of former slaves of H. M. Stuart and as individual of the same family as Prince Rivers, I sharply disagree with your assessment of Prince Rivers’ legacy. I feel your sources are limited and that your assumption seems to be only an opinion and not a fact. Prince Rivers’ story is not a story of betrayal, it is a story of triumph. I would never dream of using only the accounts of Oliver Cromwell to describe the failure or the success of the redshanks, and I am at a loss, (though I am grateful you posted the article) as to why you would use only a southern newspaper source to make your point. As I read the accounts of Contemporary Southerners I am very bewildered when I come across the injection of negativity in records, where I see none. I am constantly in my own research at The National Archives, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, finding the exact opposite. I believe you would do yourself a service by maybe contacting ancestors of Mr. Rivers to get a FULL view of his life or just reading some of the wills left by individuals like H. M. Stuart when it came to care and the condition of their slaves before and after the Civil War. I find that you do not get the best information from a person…if you ask, for lack of a better description, one of his enemies for a description. Here in Beaufort, SC I can attest to personally that African American Civil War Service was way more complex than your article even begins to touch on…

A good example? My family…

Paul Hamilton would drop his children off every morning before going to the field, at Edgerly Farm, where my family worked and owned during the Civil War. H. M. Stuart himself returned to Beaufort and would stay and would stay in contact with the domestics and the various servants who served them before the Civil War. They would witness deeds, send letters of recommendations and convey land to the same people whom they knew before this bloody conflict. Your subject, Prince River’s a relative of mine was the son of Middleton Stuart’s Driver Jack and “Hal” as he was called by those of my family who lived at Oak Point before the war, returned after the war was Robert Smalls’ physician. My great grandmother would sell vegetables and could ask favors from the white sheriff Ed McTeer. I think I am more upset at how this makes Stuart look than I am how this makes Prince look. Prince Rivers comes from Oak Point, where Jack, the plantation’s foreman, was responsible through his abilities alone absent of an overseer, in making Middleton Stuart’s widow an even wealthier woman, after his untimely death. He would continue this practice as the Headman at the only farm that was purchased by former slaves and turn impressive profits in the first year of its purchase. Jack [Robinson] much like Prince was a man universally praised as having “superior executive ability” and much like Robert Smalls, he never forgot how he learned that. You paint a picture of our families BLACK and WHITE that is truly false. Jack’s adherence to duty, Binkey’s service and all the other Stuart Slave’s service on the Plantation before and after the war would require a whole lot of mutual respect. This is who we are, and that is where Prince comes from…You do the Stuart family a disservice when you criticize the service of Prince Rivers a man who worked in their house and served them as coachman for years…who lived in their house…who learned from them…and when given the chance hoped to purchase the land they had lost during the war. Prince, “a favored slave” commands the respect of all civil war heroes to be recorded properly. True southern families, know this, you need only visit any Charleston Drawing Room to confirm this as a fact. I am saying this oonly to say, you display an animousity in your writing that confuses me especially when I have read our family documents. Dare I say, this conclusion on Prince’s character is entirely editorial and only your opinion. Prince Rivers was respected by black and white, red shirts and Republicans and you can read the account in Gonzales’ “The Black Border” to find out there is truth in this. Gonzales, a known Red Shirt, treats his description of South Carolina’s first black trial justice with an abundant amount of respect. It is Prince Rivers who begs a secessionist soldier returning home through Union Picket Lines, about to be wrongfully executive, by C. T. Trowbridge, not to take the blame for someone else’s actions. I have given you already two accounts white men Southerners and Confederates who view and remember Prince Rivers with fairness and compared with how they describe others a great deal of respect. Here in Beaufort, as slave descendants of the Heyward-Washington-Manigault libe we have very strong memories of the Stuarts and other former owners and your article would make it seem as if the black individuals who lived and were attached to them were not in a way thought well of by their former plantation owners. Countless depositions from former slaves and countless witness statements from their former owners in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. prove that what you would assume from outside sources and “yellow journalists” of the South would be the case. I, personally, can give you in my family tree example after example of how our lives never ceased being connected to those that shared the same space with us for generations. Henry Middleton Stuart, whose home was a stone’s throw away from Prince’s in Beaufort, I am confident, would tell you the same. Prince, like H. M. Stuart, was committed to his duty and his country and I can see him looking at Prince and his actions in everything, in the exact same way. When given the chance he had to fight and show what he considered, his country, that he understood that, a man not willing to fight for fight for his freedom, was not worthy of having it. I just hope that you take a chance to look into the records of the Black Civil War Heroes that you document and possibly even contact the families. My Great Grandfather Joe Huguenin, would be charged with protecting the plantation at Rose Hill while three of our cousins, former freed slaves who marched down with the 144th NY, would assist in the attempted burning and destruction of the Jasper property. The Huguenins living there today, refer to my aunts and uncles who have traced their pre civil war ancestry back to Rose Hill and Joe Huguenin would refer and do refer to us as cousins. My collateral relative Jacob Washington would serve as a camp cook for Henry Middleton Stuart while Prince whom the two sources maligned, fought on the side of the union. Each man felt he had to do what he had to do…due to duty…I hope that my remarks will inspire you to look into the accounts of the former slaves of your subjects. You will find a great deal more compassion as well as truth in the words that they are saying…I thank you again for the article, but was compelled to comment to protect the legacy of both Prince and the overall Stuart Family. I hope you include that story in your future posting.

I really appreciated the above article . Your personal perspective is a very valuable piece of the puzzle .

I am very interested in discovering more information on Prince Rivers .

I have been working on the South Carolina Rivers Family Tree on Ancestry .

My friend grew up on Rivers Hill , Beaufort Co . South Carolina . His father used to tell him that ” we have all this ( land ) because of sergeant Prince Rivers .

While researching Prince Rivers I discovered a connection to Prince through his commanding officer , Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Thomas is a distant cousin through my maternal grandfather , Rollin Wentworth Thacher . Thomas’s second wife was Mary Thacher , ( a second cousin )

My friend has taken a DNA test but I have not been able to find the link to Prince yet .

Ancestry has given suggestions for ancestors going back to 1840s . These ancestors were white slave owners . The problem is the white wife is listed as Mr Rivers great , great, grandmother . This man and his family are in their 70s & 80s . I’m trying to record their childhood memories of Rivers Hill. . This family is really amazing to me ! Words like resourcefulness, hard-working, determination , intelligence and fierce loyalty to a country that has not treated them well to be honest .

Mr Rivers is aVietnam veteran. On Martin Luther King jr Day he shared that he saw MLK speak . The ” colored ” were not allowed to hear him speak at the church filled with white people . MLK later spoke at a Black Baptist Church.

I am writing this from memory and to my knowledge it is accurate . However , there may be a few mistakes . I grew up in NY state and not very familiar with S. Carolina .

This family should be interviewed as they have first hand knowledge !