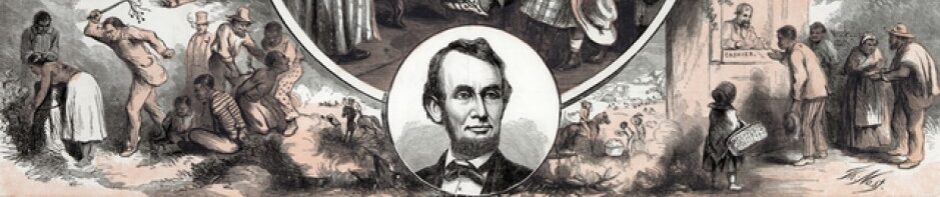

James Rumley was a 50-year-old government clerk living in Beaufort, North Carolina when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Rumley, a single man, had owned two slaves at the outset of conflict and had spent most of the previous year living bitterly under Union occupation. The Federal forces had arrived in this section of the Outer Banks in March 1862 following their victory at New Bern (March 14, 1862). To bear witness against what he considered the horrors of Union misrule, Rumley began keeping a secret diary which he maintained until the end of the conflict in 1865. Outwardly, the local clerk remained helpful to the Union occupiers and even took a loyalty oath, but his diary makes clear that Rumley never accepted the legitimacy of the occupation and deeply resented the destruction of slavery. This is one of the very few published diary accounts by a southern secessionist sympathizer living under Union occupation during the Civil War. The entire diary is not available online, but for the full-text printed version, consult Judkin Browning, ed., The Southern Mind Under Union rule: The Diary of James Rumley, Beaufort, North Carolina, 1862-1865 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009). Here are selections from Rumley’s descriptions of how former slaves and Union soldiers began implementing freedom even before January 1, 1863 followed by a remarkable entry depicting how he viewed the President’s proclamation on the day of its execution.

May 1862

“…Slaves are now deserting in scores from all parts of the country, and our worst fears on this subject are likely to be realized. The order which General [Ambrose] Burnside promised to make, to prevent them from entering his lines, has not been made. His lying proclamation was a Yankee trick. These runaway Negroes are allowed to pass the sentinels at any time, even in the night. Often white citizens are required to retire to their homes. They are welcomed at the different quarters by officers and soldiers, while the lying scoundrels who receive them declare they do not encourage them to come among them and do not want such nuisances. An infamous law of the Federal Congress [March 13, 1862 Additional Article of War], prohibiting the surrender of fugitive slaves, enables these fanatics to make their quarters perfect harbors of runaway negroes. Officers employ them in various capacities and pay them for their services, ignoring the rights of the owners and violating the law of the state. They get information from them as to the political opinions and conduct of the owners, and in some instances arrests of citizens have been made and property been seized upon negro testimony.

The soldiers go, without hesitation, into the kitchens among the negroes and encourage them to leave their owners. Some of them have been seen promenading the streets with negro wenches.

The inhabitants are filled with loathing and disgust by the presence of this pestilent army. The disastrous effects of their conduct towards the slave population have been represented to Gen. [John G.] Parke, who has taken up his quarters here for the present. He has promised to correct this evil; but does not do it.”

June 7, 1862:

“The mask, which concealed at first the hideous features of fanaticism, is now thrown off, and the conduct of the troops in reference to the slaves, has become alarming to the inhabitants. Those fanatics feel a bitter hatred towards slaveholders, and the lying stories the slaves have told them of the cruelty of their owners has made their hatred stronger. If any citizen were to chastise a disobedient slave, he would run the hazard of being mobbed by ruffianly soldiers. If an owner attempts to recover a runaway slave, he runs the same risk. Owners have permission to take their slaves wherever they find them, if they can do so without using forcible means. If the slave is willing to go the owner can take him along with him. If not the soldiers will interfere and protect the slave. The consequence is very few runaways are recovered. Citizens in search of their slaves have been threatened with violence and compelled to desist.”

December 1862:

“Our town is crowded with runaway negroes. Not only the able bodied, but the lame, the halt, the blind and crazy, have poured in upon us, until every available habitation has been filled with them. Even the Methodist Parsonage, and the Odd Fellows Lodge, have been desecrated in this way, and are now filled with gangs of these black traitors.”

January 1, 1863:

“This will long be remembered as the day on which Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation goes into operation … Many reflecting minds have for several months past looked forward to this day with deep concern, on account of the slave population in our midst. They could hardly believe that so remarkable an epoch could arrive without producing some commotion among the negroes, some tumult, some shock to society. That the shackles should suddenly fall from the hands of thousands of slaves, as silently as snowflakes fall upon the earth, and the slaves move on in their new atmosphere of freedom, with no signs of uproar, no fandangoes, no shouts, no jubilant songs to express their joy or insult their former owners, and with no more stir among them than might be produced on New Year’s Day, by a transfer from one set of masters to another, was not to be believed by any who knew what sudden emancipation once caused among this race in the Island of St. Domingo [Haiti]. Yet this is precisely the state of things we behold around us this day. The Emancipation Proclamation has taken effect today and has sundered, so far as military law can do it, the bonds that united the slave to the master, without producing a ripple on the face of the waters. This peaceful and quiet transition from slavery to freedom must find its explanation, to a great extent, in the fact that the Federal Army in this section of the state had long since, by their conduct towards the slaves, anticipated the Proclamation and virtually set them free. Besides this, the slaves may not be entirely certain that their freedom is permanent, and may have some secret dread of the approach of Confederate power.”

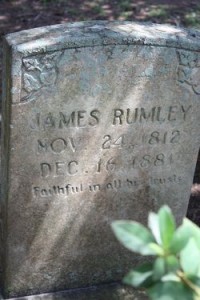

The original version of the Rumley diary is no longer available. Judkin Browning edited the text for his book The Southern Mind Under Union Rule (2009) from published versions of the diary that had appeared in local Beaufort newspapers in 1910 and 1937 and from a transcript that exists in the North Carolina State Archives. Rumley, who was born in 1812, lived until 1881, when he died at the age of 69. He was laid to rest at the Old Burying Ground in Beaufort where his headstone reads, “Faithful in all his trusts.”