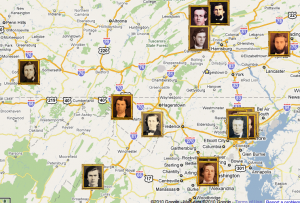

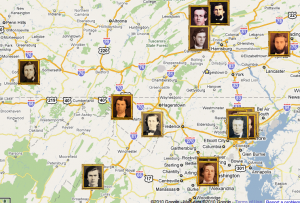

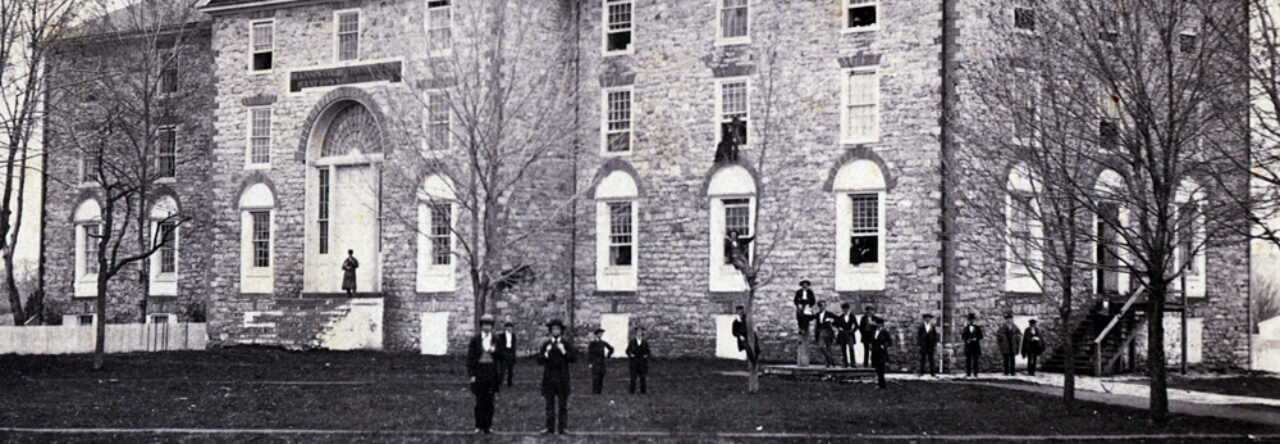

The Dickinson College Class of 1860’s graduation marked for many students the beginning of a necessary transition into an divided country. Given that thirteen students hailed from Slave States and eleven from Free States, the transition differed for each student as they returned to their homes on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. This dynamic map features several notable alumni that served, and perished, on both sides of the battlefield during the Civil War. While some did not enlist in the military, more than half of the class members noted on this map served either the Confederate or Union armies in some way.

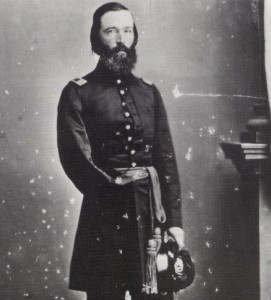

George Baylor, born in Jefferson County, Virginia, entered Dickinson College in 1857 and graduated with the Class of 1860. He initially returned home and became an assistant teacher after graduation, but once the war began he enlisted in the 2nd Virginia Infantry. By 1863 Baylor engaged Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley, was taken prisoner, and incurred various battle wounds. His reputation grew as a practical military leader and effective director of Confederate raids through Virginia in 1864. One such raid secured Baylor as a Dickinson legend. While in combat in Trevilan, Virginia, a Union soldier shot Baylor in the chest. Because Baylor wore his Union Philosophical Society badge in battle as a reminder of the organization he belonged to at Dickinson, the bullet did not penetrate his skin and he survived. The war ended soon thereafter, and Baylor sought out a profession in law.

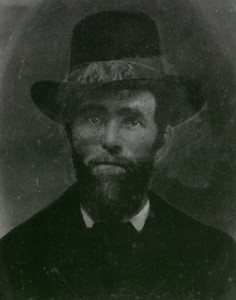

John Henry Grabill followed a similar trajectory, for once the Civil War began he enlisted in the 33rd Virginia Volunteer Infantry centered near his birthplace in Mount Jackson, Virginia. In 1862 Grabill, at the age of twenty-two years old, recruited and trained his own unit of soldiers in the Shenandoah Valley. This unit went on to fight during the retreat to Appomattox Court House in 1865. Grabill fought in several key battles himself including the Battle of Brandy Station and Battle of the Wilderness. He elaborated on these engagements as part of his general service in the army in Diary of a Soldier of the Stonewall Brigade (1909). After the war Grabill entered the field of education as a superintendent in Shenandoah County.

Baylor, Grabill, and their classmates offered several stories that contribute much to one’s understanding of the Civil War and its lasting impact on Dickinson College and the surrounding area of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. This dynamic map is one of several projects utilizing modern tools to examine these local and personal responses to the war.

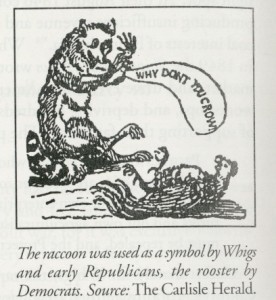

‘Americans Shall Rule America!’ The Know-Nothing Party in Cumberland County (1998)

‘Americans Shall Rule America!’ The Know-Nothing Party in Cumberland County (1998)

The Shelling of Carlisle Map

The Shelling of Carlisle Map