https://www.wevideo.com/view/3845192776

In 2024, the Associated Press polled U.S. adults on which rights and freedoms meant the most to them. In this poll, 91% of adults considered the right to vote as being the most important core American value.[1] Today, almost all citizens over the age of 18, regardless of race, color or sex can vote, but all citizens did not always have that right. The Fifteenth Amendment was a key step in the process of achieving equal voting rights. In this amendment, Congress essentially granted African American men the right to vote. Many praised the achievement, but some criticized it for not expanding beyond African Americans and granting other groups the right to vote, with outrage coming from women in particular. Despite the limitations on sex, the amendment was revolutionary, and the framers believed that their actions were revolutionary enough for the country at the time, and that anything further might have jeopardized the progress for African American men.

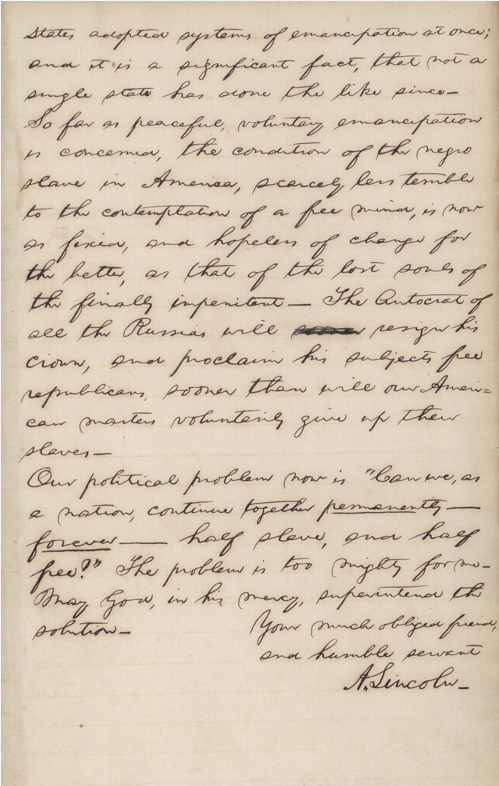

Text

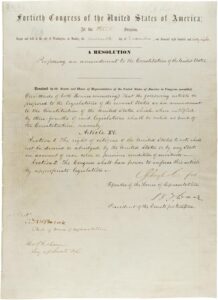

15th Amendment to the US Constitution: Voting Rights (1870) | (National Archives)

The Fifteenth Amendment contained two sections, consisting of 34 words in section one, and 12 in section two. It was fairly short, much shorter than the Fourteenth Amendment, the longest amendment ever written. Section One declared that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”[2] This section made it unconstitutional for state governments to deny black men, even former slaves, the right to vote.[3] While all American born people –men, women and children– were citizens as defined by the Fourteenth Amendment, this Fifteenth Amendment did not include women and children. Its language clearly targeted African American men. Section Two declared that “the Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”[4] This section granted Congress the ability to pass laws to uphold the guarantees of the amendment, such as later voting rights acts.

Context

The Thirteenth Amendment, passed by Congress and ratified by the states in 1865, criminalized slavery and involuntary servitude, and the Fourteenth Amendment, passed by Congress in 1866 and ratified by the states in 1868, granted citizenship to all persons either “born or naturalized” in the United States, including those who had lived as slaves.[5] Additionally, there were the Reconstruction Acts in 1867 and 1868, focusing on the former Confederate States. These acts demanded that states enforce “peace and good order” until states established loyal and Republican governments.[6] Furthermore, Section 5 of the 1867 Reconstruction Act explained that the Constitution entitled a State to representation in Congress when the people “have formed a constitution of government…framed by a convention of delegates elected by the male citizens of said State, twenty-one years old and upward, of whatever race, color or previous condition.”[7] Congress enacted these measures from March 2, 1867 to March 11, 1868. Section 5 of the 1867 law provided the basis for wording of what became the Fifteenth Amendment.

The Fifteenth Amendment went through several developments before Congress sent it to the states for ratification. Senator Henry Wilson (R-MA) proposed a version to empower states to try “the experiment of woman suffrage,”[8] but the House and Senate excluded this addition in fear of the amendment not passing.[9] After the Civil War, according to historian James Oakes, many former slaves became the “backbone of the coalition with white Republicans that rewrote the southern state constitutions,” and “as Frederick Douglass foresaw, the black vote revolutionized southern politics just as emancipation had revolutionized southern society.”[10] Republicans believed for political reasons that they should focus on African American rights.

Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment on February 26, 1869 by a vote of 144-44. In Congress, the vast majority of Republicans voted for it while Democrats voted against it. The amendment needed 3/4s of the support of the States, including the support of the former Confederate States, to achieve ratification. Some of these states opposed ratification, but other states that had radically reconstructed governments supported ratification. Furthermore, Congress required former Confederate States Mississippi, Texas, Virginia and Georgia to ratify the amendment in exchange for representation in Congress.[11] The states met the ratification threshold on February 3, 1870, nearly a year after its initial passage by Congress.

Subtext

Why did the framers of the Fifteenth Amendment exclude women? Feminists had been fighting for women’s voting rights for decades. Among them was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the author of the Declaration of Sentiments from 1848. In this document, Stanton wrote that “all men and women are created equal,” language that borrowed from the Declaration of Independence.[12] Sojourner Truth, another women’s rights activist, became noteworthy after a speech she gave at the Woman’s Rights Convention in 1851 where she stated, “I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man.”[13]

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Seated, and Susan B. Anthony, Standing ca. 1880-1902. (Library of Congress)

In 1866, the National Women’s Rights Convention merged with the American Anti-Slavery Society to form the American Equal Rights Association (AERA).[14] Abolitionist Frederick Douglass, a member of the AERA, aligned himself “firmly among the Republicans,” as a result of “the threat of an overtly racist Democratic Party.”[15] Douglass was a supporter of women’s rights and was friends with women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony, but in the aftermath of the Civil War, Douglass argued with Anthony over voting rights. Douglass believed that African American men were due the right to vote. He stated that the ballot was a “question of life or death” for southern Black men but not for women.[16] In 1867, Anthony and Stanton, both members of the AERA, traveled to Kansas to advocate for universal suffrage, but felt saddened when they learned that other members of the group had abandoned women’s suffrage in order to focus solely on African American male suffrage.[17] The AERA dissolved when the framers omitted sex from the Fifteenth Amendment.[18] Douglass’ assertion that the ballot was a “question of life or death” for black men but not women suggested how the Republican framers justified excluding women from the Fifteenth Amendment. They feared that promoting “universal” rights would jeopardize the progress for African American men.

Conclusion

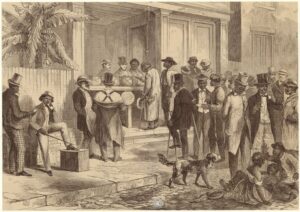

Freedmen Voting In New Orleans, 1867. (Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library)

Despite its limitations, the Fifteenth Amendment revolutionized voting rights for African Americans, many who had lived in slavery just a few years prior to its ratification. Yet while African Americans and abolitionists praised the ratification, the decision to not include sex as a protected characteristic angered women’s suffrage movements for decades. Today, Americans consider the right to vote to be one of the most important core American values, as illustrated by the recent AP poll. But it is important to remember that people did not obtain equal voting rights easily. The Nineteenth Amendment finally granted all American women the right to vote in 1920.

[1] Gary Fields, “Yes, We’re Divided. But New AP-NORC Poll Shows Americans Still Agree on Most Core American Values,” AP News, April 3, 2024, [WEB]

[2] “15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Voting Rights (1870),” National Archives, Last Reviewed May 16, 2024, [WEB]

[3] [WEB]

[4] “15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Voting Rights (1870),” National Archives, Last Reviewed May 16, 2024.

[5] “14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Civil Rights (1868).” National Archives, Last Reviewed March 6, 2024, [WEB]

[6] “Reconstruction Acts (1867-1868),” National Constitution Center, 2025, [WEB]

[7] “Reconstruction Acts (1867-1868),” National Constitution Center, 2025.

[8] Malik Ali, “The Importance of the 15th Amendment,” Teaching American History, August 31, 2023, [WEB]

[9] Malik Ali, “The Importance of the 15th Amendment,” Teaching American History, August 31, 2023.

[10] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007), 264.

[11] “Black Voting Rights: The Creation of the Fifteenth Amendment” HarpWeek, 2005, [WEB]

[12] “Declaration of Sentiments (1848) – Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.” (House Divided Project), [WEB]

[13] “Sojourner Truth, Woman’s Rights Speech (1851) – Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.” (House Divided Project), [WEB]

[14] Christopher Abernathy et al., “Reconstruction,” Nicole Turner, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018). IV. [WEB]

[15] Oakes, 280.

[16] Oakes, 288.

[17] Yawp, IV.

[18] Yawp, IV.