By: Olivia Whittaker

https://www.wevideo.com/view/3842739497

Introduction

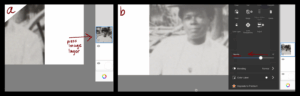

At just 22 years old, Amanda Gorman was the youngest inaugural poet ever, and faced a challenge not quite shared by her five predecessors. Joe Biden’s 2021 inauguration came just two weeks after violent mobs had stormed the U.S. Capitol in an attempt to overturn the presidential election. With her poem, The Hill We Climb, Gorman strove to promote national unity in the wake of an insurrection without lapsing into political neutrality or downplaying the trauma of the country. She struck this balance through her portrayal of a “ bruised but whole” America, acknowledging its flaws while emphasizing its triumphs in a hopeful look towards the future.

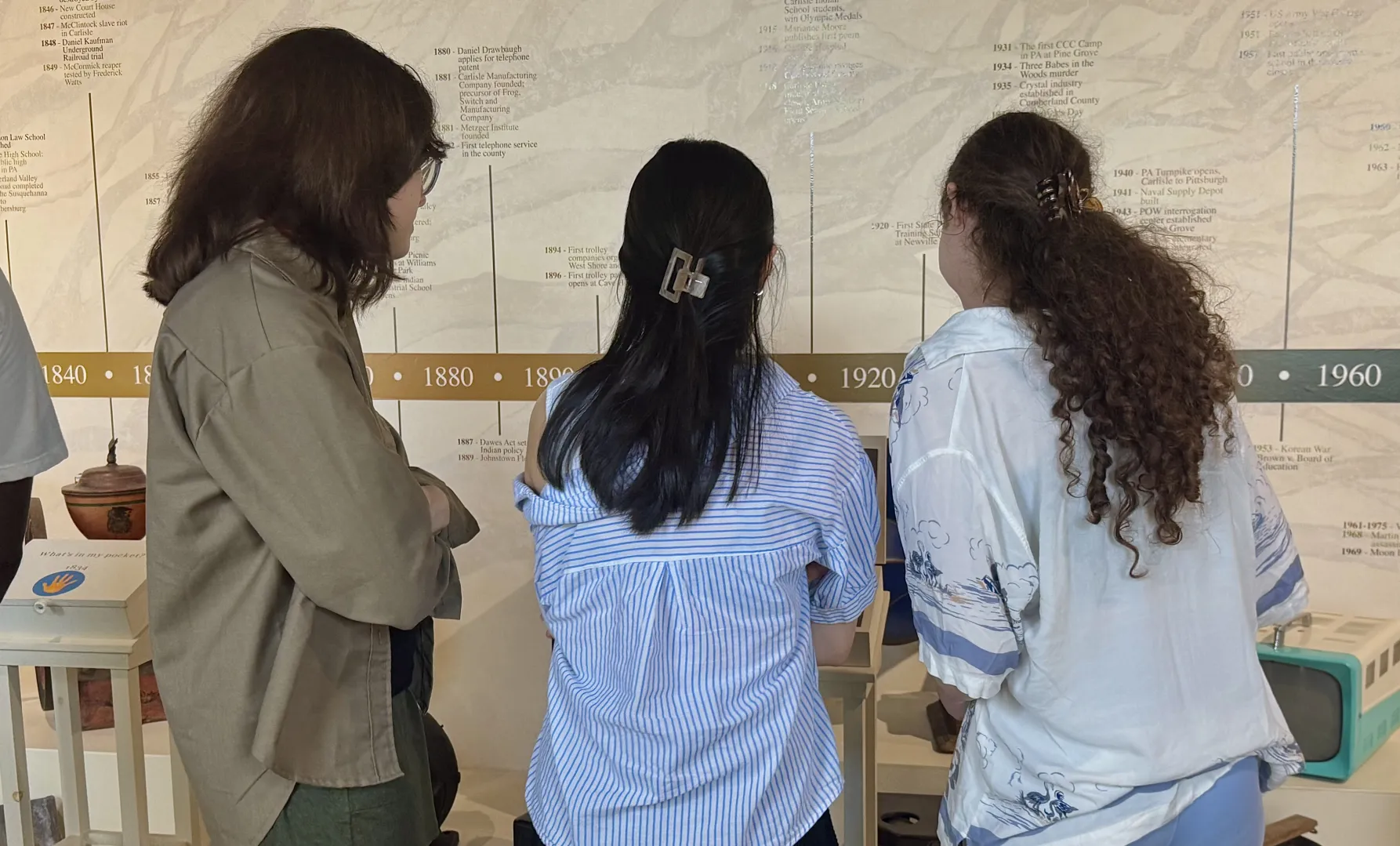

U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris applauds after Amanda Gorman recited “The Hill We Climb” during the inauguration of Joe Biden on the West Front of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, U.S., January 20, 2021. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

Text

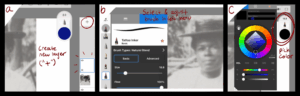

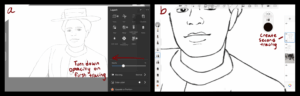

The Hill We Climb is a 723-word poem composed of 110 lines, with stanzas varying by publication. The poem is free verse, meaning that it doesn’t rely on a consistent rhyme scheme or meter, resulting in a more speech-like cadence. Its opening evokes the emergence of a new era, establishing the motif of a new “dawn.” Early lines allude to America’s ongoing fights against racism and other forms of prejudice, and subtly reference the COVID-19 pandemic as a unifying common struggle. The middle of the poem reflects on the January 6th insurrection and the resilience of democracy. Finally, the poem concludes with a powerful call for unity, urging the nation to “rise” together and build a brighter future for all. The Hill We Climb’s thematic structure can be read as a recurring arc: what we have been through, how we’ve responded, and who we are becoming as a nation. For example, after “never ending shade,” we “braved the belly of the beast,” and we now strive to “forge our union with purpose.” Though we experienced “a force that would shatter our nation,” we “found the power to author a new chapter” and emerge “a country that is bruised but whole.” This repeating pattern reflects the ongoing but often nonlinear or even cyclical nature of progress.

Context

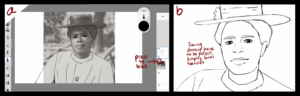

Gorman was born in Los Angeles and raised by a single mother alongside her two siblings. As a child, she had an auditory processing disorder and speech impediment, which she overcame through poetry and public speaking. In 2017, she became the first ever National Youth Poet Laureate at 19 years old, and toured the country reciting poetry with themes such as social justice and climate change. Jill Biden discovered Gorman at a reading in the Library of Congress during this time, three years before recommending her to the inaugural committee.[1] The Hill We Climb was the sixth ever inaugural poem, continuing a tradition that began in 1961 with the inauguration of John F. Kennedy, and has been sustained by nearly every democratic president since.

Supporters of President Donald Trump riot at the U.S. Capitol Building on January 6, 2021. Shay Horse/Getty Images

The inauguration came at a time of great national tension. Racial conflict and political divides had been on the rise for the past four years, and the wounds of the COVID-19 pandemic were still fresh throughout the country.[2] Two weeks before the inauguration, while Congress convened to certify the 2020 election results, President Donald Trump claimed that the election was “stolen,” declaring to his supporters: “We’re going to walk down to the Capitol…we have come to demand that Congress do the right thing and only count the electors who have been lawfully slated.”[3] During the speech, mobs of Trump supporters swarmed the U.S. capitol. Within minutes, thousands had surged past police and breached the capitol building. Staff barricaded themselves in rooms and hid under tables as the violent mob tore through.[4] Political conflict had always been integral to American democracy, but so too had peaceful transfer of power (at least since the Civil War), and the January 6 insurrection shook the country by defying that tradition.

Subtext

Gorman described her primary goal with The Hill We Climb as inspiring unity. “What I really aspire to do in the poem is to be able to use my words to envision a way in which our country can still come together and can still heal,” she told the New York Times. “It’s doing that in a way that is not erasing or neglecting the harsh truths I think America needs to reconcile with.”[5]

Black writers throughout American history have walked a tight line between criticizing and alienating their white audiences. In 1773, Phillis Wheatley’s poem, On Being Brought from Africa, carefully challenged the racist assumptions of her white Christian audience, reminding them that black people “may be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.” She padded her sharp anti-racist message with appeals to Christian morality, even describing her American captors as merciful for bringing her to a Christian land where she could seek “redemption.” In an age of slavery, the poem’s sympathetic tone was the armor it needed to promote abolition without provoking or antagonizing its audience. And while Gorman operated in a contemporary culture without slavery and where racism is condemned, her rhetorical balancing act was not so different from Wheatley’s. Her most political stance was against the January 6 rioters as “a force that would destroy our country,” but she did not linger on the topic to criticize the insurrectionists. Instead, she focused on America’s shared struggles and triumphs, unifying her audience under collective experiences and the aspiration of “a country that is bruised but whole, benevolent but bold, fierce and free.”

Conclusion

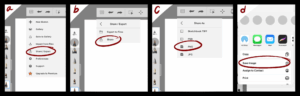

The Hill We Climb garnered widespread acclaim. Democratic political figures such as Michelle and Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Stacey Abrams sung its praises, as well as writer Lin Manuel Miranda, whose musical Hamilton Gorman referenced in the poem.[6] Conservative reactions were more mixed, though relatively mild— the work was not notably divisive upon its debut, with even right-leaning news outlets like Fox reporting on it favorably. But stronger pushback came in 2023, when a Florida school controversially restricted the poem after a parent claimed that it would “cause confusion and indoctrinate students,” that it was “not educational” and that it contained indirect “hate messages.”[7] The poem was removed from the elementary school library. The 2023-2024 book ban surge saw over 10,000 instances of banned books (from 4,218 unique titles) in public schools. One organization has documented “nearly 16,000 book bans in public schools nationwide since 2021, a number not seen since the Red Scare McCarthy era of the 1950s.” [8]

Citizens protest book bans in Georgia in 2022. (Photo: John Ramspott)

Trump also won a second term in the 2024 election, and has since issued an executive order titled Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling (2025), which, among other things, aims to cut federal funding for public schools that critically discuss systemic racism, stating that “innocent children are compelled to adopt identities as either victims or oppressors solely based on their skin color and other immutable characteristics.” How Gorman’s declarations of national harmony and triumph will age throughout this new era is uncertain, but one line in particular stands out as a reminder: “ while democracy can be periodically delayed, it can never be permanently defeated.”[9]

[1] Liesl Schillinger, “How Amanda Gorman Became the Voice of a New American Era,” The Guardian, January 22, 2021, [WEB].

[2] Pew Research Center, “How America Changed During Donald Trump’s Presidency,” Pew Research Center, January 29, 2021, [WEB]

[3] NPR, “Read Trump’s Jan. 6 Speech, A Key Part of Impeachment Trial,” NPR, February 10, 2021, [WEB].

[4] “Capitol riots timeline: What happened on 6 January 2021?”, BBC News, August 2, 2023, [WEB].

[5] Alexandra Alter, “Amanda Gorman Captures the Moment, in Verse,” The New York Times, January 19, 2021, [WEB].

[6] “Amanda Gorman: Biden Inauguration Poet Calls for ‘Unity and Togetherness’,” BBC News, January 21, 2021, [WEB]

[7] Bill Chappell, “Amanda Gorman’s Poem Was Banned in One Florida School. Now It’s a Bestseller,” NPR, May 25, 2023, [WEB].

[8] PEN America, Cover to Cover: An Analysis of Titles Banned in the 23-24 School Year, February 27, 2025, [WEB].

[9] Amanda Gorman, The Hill We Climb, [WEB].