Abraham Lincoln’s Letter to George Robertson (1855)

https://www.wevideo.com/view/3836940215

In 1855, Abraham Lincoln sounded worried. “I think, that there is no peaceful extinction of slavery in prospect for us,” he wrote to George Robertson, an acquaintance and political ally from Kentucky [1]. Was he predicting a civil war? Understanding why Lincoln tried to warn Whigs like Robertson to mobilize against slavery requires a close reading with political context from the 1850s and an understanding of why Lincoln turned to the Republican Party at this time. Republicans stood firmly against the spread of slavery and were more open about denouncing its evils than the Whigs had ever attempted. To persuade Robertson about the wisdom of this approach, Lincoln emphasized the American Revolution and the value of freedom. He chose not to mention the horrors of slavery to this Kentucky slaveholder.

Description of the Text

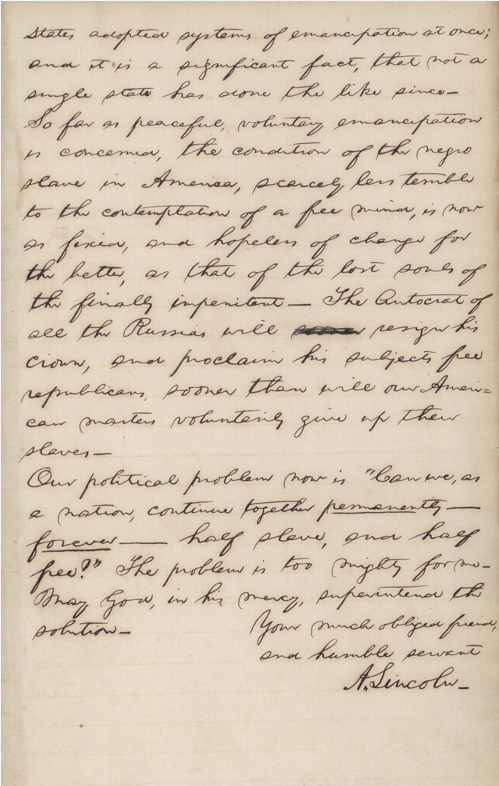

Lincoln’s Letter to Robertson (Papers of Abraham Lincoln)

Lincoln wrote the 503-word letter in cursive on two pieces of lined paper, using both the front and back of the first page. When he needed to edit, Lincoln crossed out several words and wrote their replacements in with carets. To close, he signed the letter “A. Lincoln.” He started by admitting that the recipient had “very reasonable” views on slavery and the Missouri Compromise. However, Lincoln moved to counter these ideas by pointing to Henry Clay‘s failure to secure gradual emancipation in Kentucky in 1849 after the state amended its constitution. Clay did not hold abolitionist views and did not think that the federal government had the power to abolish slavery nationally as the Constitution does not explicitly mention the topic. Lincoln wrote that this event had “extinguishe[d] that [gradual emancipation] hope utterly”[2]. He then lamented the dead spirit of the Revolutionary War and how many Americans had locked themselves to their ideals of slaveholding. He said that the Declaration of Independence’s idea that “all men are created equal” had proven to be “a self evident lie” for “fat” politicians who had forgotten the country’s founding egalitarian principles. Lincoln used sarcasm to remark that the Fourth of July’s only purpose was “for burning fire-crackers!!!”[3]. Lincoln did not let the irony of Americans celebrating independence while others were enslaved go unnoticed, underlining “for burning fire-crackers” and adding three exclamation marks. Finally, at the end of the letter, Lincoln pointed to the future, doubting if the country could remain together while so strongly divided on the issue of slavery. He asked “Can we, as a nation, continue together permanently— forever— half slave, and half free? The problem is too mighty for me”[4]. Lincoln underlined the synonymous words “permanently—forever” to call attention to how difficult it would be for the current conditions to perpetually continue.

Context on the Republican Party

Map of the Missouri Compromise (Library of Congress)

Robertson left a copy of his book, Scrap Book on Law and Politics, after a visit to Springfield. Robertson had fought against federal governmental intervention over slavery in Arkansas in 1819, and detailed ideas of gradual emancipation in the book. Additionally, he discussed his role in the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. To explain why he disagreed with the moderate view that Southern slavery would gradually end as it had in the North, Lincoln referenced the failures of Henry Clay’s compromises. While the divisions of free and slave states admitted to the Union postponed war, they did not offer a final solution. No state had emancipated their enslaved people since New Jersey in 1804; failed efforts by Virginia in 1831 and Kentucky in 1849 demonstrated that slavery would not naturally extinguish. By equating Robertson’s views with Clay’s actions, Lincoln undermined Robertson’s confidence that the issue would resolve itself. The ongoing disagreement over slavery between Robertson and Lincoln signaled the rifts between those with anti-slavery viewpoints.

However, the Republican Party had recently been formed, uniting Whigs, Know Nothings, and Free Soilers. Matthew Pinsker writes that the party launched itself onto a national stage by keeping “a single-minded focus on the slavery issue while accommodating as broad a coalition of men as possible” [5]. Although Lincoln had not called himself an abolitionist, his politics were often seen by Democrats as what historian James Oakes calls “a flagrant appeal to radicalism” [6]. This reputation would have stood in his mind as he appealed to the moderate Robertson to stand behind Republican principles.

Subtext on Using the Declaration

Lincoln used the language of the revolution and the Declaration of Independence to remind Robertson that he was not far removed from being “enslaved” himself and that as a Whig he should stand up against oppression. Lincoln felt angry that Americans had sterilized the war, turning the Fourth of July into a holiday instead of a reflection on liberty. For Lincoln, patriotism meant fighting for equality for both White and Black people. But Lincoln did not try to sway Robertson, a slaveholder, with appeals to the humanity of enslaved people.

Lincoln had seen the experiences of enslaved people; in a letter written in 1844 to an old Kentucky friend Mary Speed, Lincoln detailed the experience of seeing twelve enslaved people chained together, writing “In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their wives and children”[7]. In another August 1855 letter, a still distressed Lincoln wrote to friend Joshua Speed, his closest friend and Mary’s brother, that the sight was a “continued torment” for him [8]. Lincoln knew that appeals over slavery’s violence would not affect a slaveholder like Robertson. Instead, he chose to appeal to America’s founding ideals, even if ignoring the sight of the slave coffle betrayed some of his strongest emotions. This exclusion of discussion of conditions of slavery conveyed Lincoln’s willingness to speak to a targeted audience. At this point in his career, Lincoln tested different variations of anti-slavery rhetoric, figuring out how to address people across the spectrum in a deeply divided nation.

Depiction of Lincoln’s House Divided speech (Library of Congress )

Although Lincoln had told Robertson that the question of slavery was “too mighty for him,” he eventually chose to answer it on June 16, 1858, during his address to the Illinois Republican State Convention after the party nominated him for the Senate. There, he stated that “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free”[9]. This famous statement echoed the rhetoric in this letter. Now on a national stage, Lincoln still understood slavery to be a divisive issue that could tear the country apart and appealed to his Republican audience to stand firmly against it.

[1] Abraham Lincoln to George Robertson, August 15, 1855, in Papers of Abraham Lincoln Digital Library, [WEB].

[2] Abraham Lincoln to George Robertson, August 15, 1855.

[3] Abraham Lincoln to George Robertson, August 15, 1855.

[4] Abraham Lincoln to George Robertson, August 15, 1855.

[5] Matthew Pinsker, “Man of Consequence,” History Teacher 16 (2009): 16-33. [WEB].

[6] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008), xiv. [WEB].

[7] Abraham Lincoln to Mary Speed, September 27, 1841, in Lincoln’s Private Letters on the Sectional Crisis (1841, 1850), [WEB].

[8] Abraham Lincoln to Joshua Speed, August 24, 1855, in Lincoln’s Private Letters on the Sectional Crisis (1841, 1850), [WEB].

[9] Abraham Lincoln, “House Divided Speech” (speech, Illinois Republican State Convention, Springfield, IL, June 16, 1858). [WEB].

Leave a Reply