By the end of spring semester 2019, we will submit a report to the President’s Commission on Inclusivity that will summarize our investigation into the college’s longstanding ties to both slavery and antislavery. We will also offer an analysis of how the college and the community of Carlisle have remembered –or have chosen to ignore– some of these subjects over the years and suggest how they might better commemorate them in the future.

On this page, we are asking members of our community to consider two questions that will be essential to this forthcoming report:

- Should the college consider renaming any buildings or removing any memorials that commemorate Dickinsonian slaveholders?

- Should the college consider adding memorials that commemorate the contributions of enslaved people or free African Americans who worked here?

This entire website and the physical Dickinson & Slavery exhibit at the House Divided Project studio (61 N. West Street) both serve to provide context for these profound questions, but we will provide a concise summary of these issues below. At the bottom of the page, readers will then be able to post their own comments, or if they choose, they can email them directly to hdivided@dickinson.edu. Selections from these comments will be incorporated into the report presented in 2019 to the President’s Commission on Inclusivity.

Should the college consider renaming any buildings or removing any memorials that commemorate Dickinsonian slaveholders?

There are dozens of buildings and memorials of various types across the Dickinson campus named after a wide range of individuals from the institution’s past. We have identified at least seven former slaveholders who are currently being honored with a named buildings or sections of the campus, but they can probably be separated into two distinct categories:

Slaveholders who freed their own slaves and / or later came to oppose slavery:

- James Buchanan

- John Dickinson

- Benjamin Rush

- James Wilson

Dickinson, Rush and Wilson were all important Founding Fathers of the nation as well as the college. John Dickinson, our namesake, was the largest slaveholder of this trio, but he memorably spoke out against slavery at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, warning that they were all risking the appearance of hypocrisy by establishing a nation around “this new principle” of “a Right to govern Freemen on a power derived from Slaves.” Despite owning his own slave, whom he emancipated quite slowly, Benjamin Rush, the true founder of our college, agreed with Dickinson and urged the abolition of slavery in America. James Buchanan was never a slaveholder, but he did help arrange for legal freedom coupled with prospective indentured servitude for two enslaved Virginians in 1835 (a mother and her daughter). Yet the daughter died almost immediately and then the mother, Daphne Cook, ran away. If they had lived and remained in his household, it’s possible these women would have served Buchanan for years without wages (to pay off their “debt” to him). (NOTE –this information has only recently been updated in 2021 and corrects the previous historical record). Regardless, as president, Buchanan became notorious for his “doughface” or proslavery leanings.

Slaveholders (or pro-slavery figures) who never renounced slaveholding:

- John Armstrong

- Thomas Cooper

- John Montgomery

John Armstrong was a leading though sometimes-controversial military figure during the colonial and revolutionary eras. He was also an early college trustee who owned slaves. John Montgomery was perhaps the most active of the early college trustees, but he was not merely an unrepentant slaveholder, he bought and sold human beings as well. But perhaps the most inexplicable commemoration of a slaveholder on our campus belongs to Thomas Cooper, the namesake of Cooper Hall. Cooper briefly served as a faculty member at Dickinson in the early nineteenth century –and he was a great scientist– but he also became quite controversial later in his career as pro-slavery intellectual in South Carolina.

Should the college consider adding memorials to commemorate the contributions by enslaved people or free African Americans who worked here?

There were dozens of African Americans who lived and worked around the Dickinson College campus during the nineteenth century. Even earlier there were also some enslaved people employed to help construct the first buildings on campus. But out of these figures, only one, a former slave named Noah Pinkney, has ever been recognized by the college with an official commemoration ( a plaque near East College gate). Yet Pinkney is only one of perhaps three central black figures from the college’s nineteenth-century past:

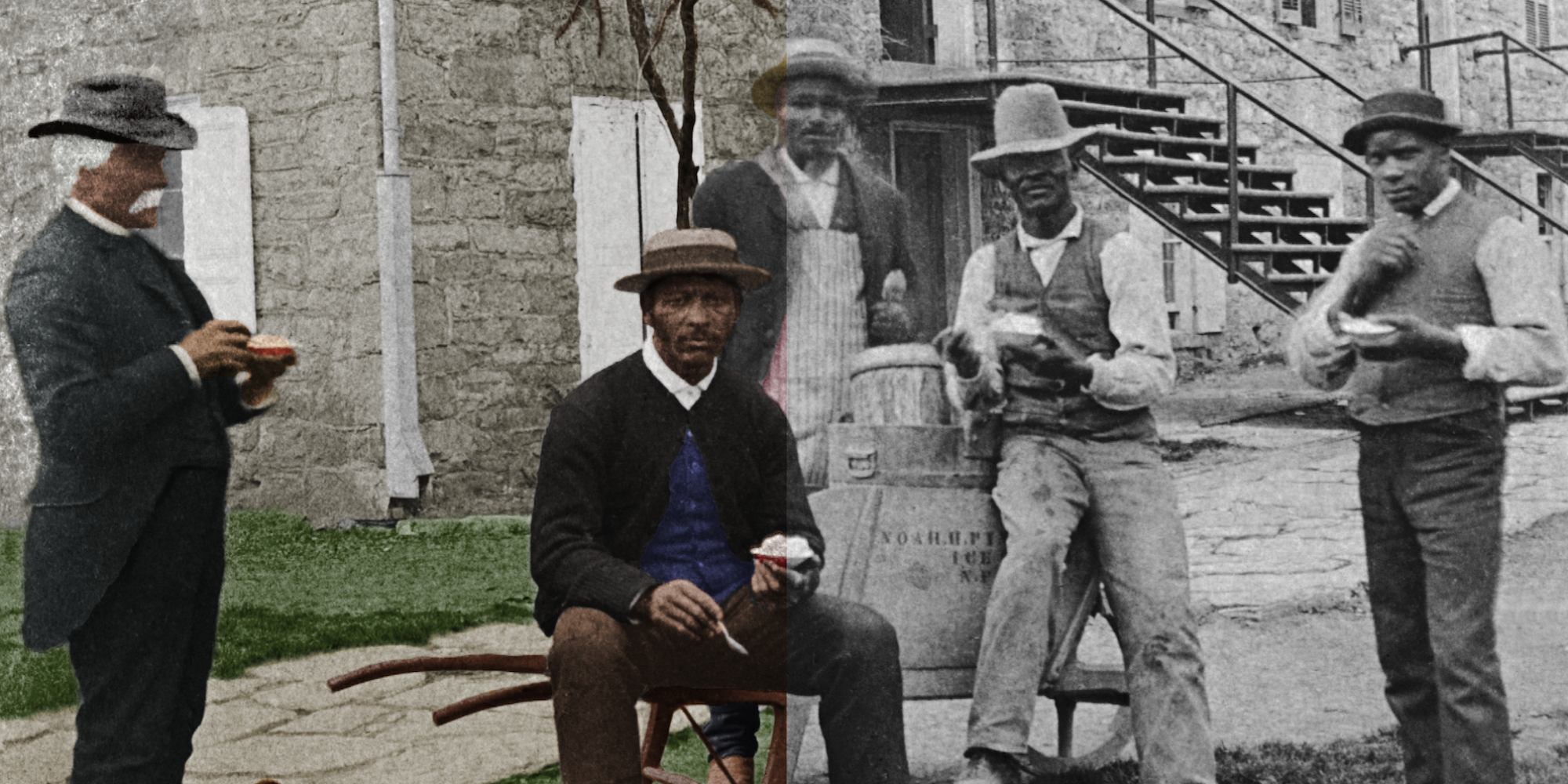

Noah Pinkney escaped from slavery in Maryland and later was present with the Union army at Appomattox. He became such an icon at Dickinson after the Civil War that the college erected a plaque in his honor during the 1950s. Pinkney and his wife Carrie sold pretzels, sandwiches, ice cream and other treats to generations of students.

Henry W. Spradley was a former enslaved stonemason from Virginia, who escaped during the Civil War, fought in the Union army, and later became the most beloved janitor at Dickinson. He participated in the groundbreaking ceremonies for Denny Hall. The school even closed for a day in his honor following his death in 1897.

Robert C. Young was the longest-serving employee of Dickinson before the 21st-century. Born enslaved in Virginia, Young began his work on campus as a household servant, became a janitor and then eventually head of campus security. He worked at Dickinson for over 40 years. In 1886, he also fought to get his eldest son admitted to the college.

While I agree the period of slavery was sad and regrettable, it has to be looked at in the context of our times. Culturally and legally it was acceptable in the times it took place and before it became an issue. To change building names of former slave holders would be wrong. These slaveholders made major contributions to our society or the landmark (or building) wouldn’t have been named after them.

Some of the most celebrated people in our American history were slaveholders. Examples are George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Would we be changing the names of the University, bridges and other landmarks from Washington or Jefferson to something else.

Although Al Sharpton and Oprah Winfrey are fine people who are current contributors, I can’t imagine changing the Jefferson Memorial to Al Sharpton memorial. Where would we stop? And, if we did, would we change those names if after a period of years society changes to the extent there are concerns about their activities.

It is important, though, to recognize context. For want of a better example, ax murders were always considered reprehensive, illegal and evil. So if a history of ax murder is discovered on the part of a landmark named after a historical figure, then, yes, change the name.

One reason why we study history is to learn from our achievements and our mistakes. Slavery was a mistake. We have learned from it.

As much as we would like, we cannot change our history.

Yes, the college should consider renaming buildings, removing names of slaveholders and advocates of slavery, and commemorating former slaves.

I think the college should rename buildings or other commemorations of Dickinson slaveholders. The Dickinson community has had so many amazing individuals, whether in scientific or humanities disciplines, that much more strongly and clearly uphold the values and ideals on which we supposedly base our institution, and I think it would benefit the entire community to commemorate those individuals. Even if individuals like Benjamin Rush or John Dickinson did do great things and upheld some of the values we believe in, holding them up as the ONLY icons of our community undoubtedly is not very welcoming or inclusive of students of color, and suggests that we can ignore these undesirable qualities just because those running this institution (who were and still are primarily white men) decided they weren’t as important. I don’t think this means we should never discuss people like Rush or even Cooper and the complications of their lives (and the times in which they lived), but just giving them a statue and saying they were great is not at all the type of open discussion that this campus is all about.

(continued from last comment) I think including formerly enslaved or free Black men and women who were a part of the campus community would be a great change in direction. These individuals really embodied a lot of the values that we have been pushing on campus in recent years, and so sharing their stories can have a really great impact on Dickinson, the Carlisle community, and maybe even further. Commemorating these people shows that we value the lives and contributions of those with less privilege and power than the school’s founders, and it shows that we embrace diversity in our past and our present. Both of these ideas are very important in terms of shaping our campus values and the message we send to the public, and in terms of making more meaningful connections with the Carlisle community.

In my opinion, the college should work to place slaveholding founders such as Rush, Dickinson and Montgomery in context. For instance, a wayside marker placed beside the Rush statute already on campus could help contextualize Rush’s slaveholding with his avowed abolitionist sentiments. At present, the monument celebrates Rush as an abolitionist without any reference to his own complex, and at times contradictory stances on slavery and race. When it comes to Cooper Hall, I would support renaming the building in honor of Robert Young, a former slave who worked at Dickinson for more than four decades, and whose son temporarily integrated the school in the mid-1880s. Not only was he a pro-slavery writer, but Dickinsonians should also bear in mind that Thomas Cooper only taught at Dickinson for a relatively brief period (about four years), and left under a storm cloud after a protracted battle with the college’s president. As was recently uncovered, the building wasn’t even named after Cooper until the 1990s. I would respectfully suggest that the Dickinson community chose to honor Robert Young, who left a far more positive and impactful legacy on campus in over four decades of service to the college.

I strongly believe that Dickinson should change the names of the buildings named after slaveholders, and instead use names of formerly enslaved or free black men and women who contributed to Carlisle or the Dickinson community. The choice to name these buildings after slaveholders puts an ugly face on the Dickinson community and it actively goes against the college’s values. Instead, by including names of populations who have been underrepresented, such as Pinkney, Spradley or Young, Dickinson will be showing the world what it truly stands for- equality, education, justice, and civic engagement. Although some argue that this is “ignoring history”, I would argue the opposite. We have ignored enslaved or formerly enslaved individuals in history for far too long, despite the incredibly positive impacts they have made on the community. We should certainly include commemorative information next to each building, explaining the history of the buildings and why the name has been changed. This will help to emphasize Dickinson’s history, even when Dickinson has made poor choices to name buildings after slaveholders, so that we can own up to the decisions we have made and clearly explain why we have decided to change these names for the betterment of the community.

I think the college must rename the buildings or other commemorations of Dickinson slaveholders on campus and in the Carlisle community. There are many different avenues to which the college can explain the controversial history of these figures along with commemorating their accomplishments and attributions to the college. However, the college and higher education in large, have went far too long allowing the figures who helped form this country and these institutions live in glory and honor without addressing their complex lives. By providing memorials to commemorate free African Americans or enslaved black people, the college will provide the nuance and context necessary to deal with this college and its history that is just. While I don’t think this truly does the work of embracing diversity in the present, it at least holds the institution accountable by addressing its historical ties with slavery.

The names of these buildings reflects our history. Renaming them for the sake of appeasing current “politically correct” viewpoints only serves to assure that we’ll repeat the mistakes of long ago.

This countries history bares the scars of our birth and growth into what we are today. Stop trying to censor the portions that you deem offensive.

History has shown America is not a white nation, although many would think it should remain so; however, in eradicating the plaques of the founding fathers’ of Dickinson College would be an error. To further the discussion of America’s past and its multiculturalism and its positive steps toward ‘freedom and justice for all,’ plagues should simply be revised to indicate the gravity of the error of past leaders and founders of the college. Another history lesson for us all.

The Holocaust Museum in Washington defines, by its memorial of those slain and the Nazi villains, the past atrocities in Germany. If we do not examine our past (and some would like to forget THAT period of time), we are destined to repeat it.

Please revise the plaques to indicate not only achievements of those founders but their failures. Please honor all who rose above their slavery backgrounds to serve at the college, as this stands to serve that, in that time, African-Americans could do as well, if not better than some of their white counterparts. On the top of the list of those few men who can be honored should be Robert Young. Young had a duty to protect his family by stepping into a job not often admired (for primarily white students) and rising to head of security to push for his son’s admittance to the college and is a hero in my opinion.

I believe the college should consider renaming buildings and adding memorials to commemorating the contributions of past Black employees and enslaved people that worked here. It is important to honor the narratives of those who were forced to sacrifice the freedom of body and mind to lay the foundations of the institution we have today. The free black men who worked at Dickinson helped to insure countless of students at the time and in the future would receive a quality education all while they and their own children were barred from such classrooms. That should not be forgotten. To ignore or not celebrate their contributes to Dickinson is to white wash the history of this college. As a Black student at Dickinson, I am must wrestle the fact that founders like Rush, and alumni like Buchanan and Cooper, never intended me to have this education. Each day I walk around campus with a slaveholder’s name across my chest. Learning about the black people that helped to shape Dickinson has helped me recognize my place here is not that as an invader trying to make room in a system inherently built against me, but as quasi descendant continuing the legacy Black Dickinsonians started from the very beginning. To see these men, women, and their stories honored alongside those of Rush and Buchanan would instill a sense of pride an acknowledgement in me. It would also show Dickinson is unafraid to self-reflect and complicate history. It is important to acknowledge that the life of an elite land and slave holding white man was not the only reality of the time. There were other realities too. One was of a former slave, turned janitor and activist, who believed his son deserved the best education, and was willing to fight for it. Even if he didn’t found a college or become a president, the reality is just as valid, and world changing, as any other.

Yes, on-campus buildings that feature the names of slaveholders associated with Dickinson should be renamed. Renaming those buildings is not an attempt at concealing an unsightly part of our history; rather, it is a recognition of the fact that Black narratives have been and continue to be erased on Dickinson’s campus, and a clear message that that erasure is unacceptable . Transparency needs to be a priority, so information about why the buildings were renamed should be available.

Yes, monuments to the Black figures who have shaped this campus should be erected. To only commemorate white figures is to ignore the physical and intellectual contributions of Black figures.