By Matthew Pinsker GO TO “LINCOLN” MOVIE TEACHER’S GUIDE

The public reaction from most historians to the “Lincoln” movie has been positive, although there have been a few important holdouts and plenty of corrections and suggestions from the academic community that should matter greatly to anyone attempting to teach the film. There has also been a revealing scuffle over which sources most influenced scriptwriter Tony Kushner.

Eric Foner

The leading academic critics of Spielberg’s movie so far have been Eric Foner, Kate Masur, and Patrick Rael. Foner, a Pulitzer Prize-winner and one of the most respected historians in the field, claims the movie “grossly exaggerates” its main point about the stark choices confronting the president at the end of the war over abolition or peace (Letter to the Editor, New York Times, November 26, 2012). Masur accuses the film of oversimplifying the role of blacks in abolition and dismisses the effort as “an opportunity squandered” (Op-Ed, New York Times, November 12, 2012). She follows up on that criticism with a piece for The Chronicle of Higher Education suggesting several other interpretive possibilities that Spielberg might have pursued to more fully integrate his film (November 30, 2012). Rael (Bowdoin College) provoked a lively discussion at H-Slavery by arguing in an extensive critique that the film is rooted in “some of the oldest, most out-dated strands of scholarship” (January 7, 2013).

Harold Holzer, co-chair of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation and author of more than 40 books, served as a consultant to the film and praises it but also observes that there are “no shortage of small historical bloopers in the movie” in a lively piece which details many of them for The Daily Beast (November 22, 2012). Along with Holzer’s notably balanced assessment, one of the most helpful early historical evaluations of the film comes from Joshua Zeitz writing for The Atlantic (November 12, 2012). Zeitz, who is currently preparing a biography of Lincoln aides John Nicolay and John Hay, considers the depiction of the president and his political challenges to be “masterful” but finds extensive fault with the one-dimensional portraits of nearly all the president’s men. He writes, “With the exception of Secretary of State William Seward (played convincingly by David Strathairn), Lincoln presents almost every public figure as either comical, quirky, weak-kneed or pathetically self-interested.”

Other historian / fact-checkers have been more kind. Allen Guelzo, Gettysburg College, writing for The Daily Beast has some plot criticism, but argues that, “The pains that have been taken in the name of historical authenticity in this movie are worth hailing just on their own terms” (November 27, 2012). David Stewart, independent historical author, writing for History News Network, describes Spielberg’s work as “reasonably solid history” and tells readers of HNN, “go see it with a clear conscience” (November 20, 2012). Lincoln Biographer Ronald White also admires the film, though he noted a few mistakes and points out in an interview with NPR, “Is every word true? No.” (November 23, 2012). For the Chronicle of Higher Education, Louis Masur finds the opening scene (where a black soldier recites the Gettysburg Address) “contrived” but otherwise considers the rest of the film to be a masterpiece that truly “conjures Lincoln’s world” (November 26, 2012). The Los Angeles Review of Books produced one of the best summaries detailing the range of historian reactions in a piece by Kelly Candaele (December 14, 2012). The article quoted extensively from CUNY historian James Oakes who offers a particularly nuanced critique of Kushner’s interpretive choices. Oakes has praise for the screenwriter’s decision to draw together the politics of abolition and peace talks, but finds “more troubling in terms of historical accuracy” Kushner’s insistence that conservative Republicans (such as the Blair family) opposed the slavery amendment. In his interview and in his new book, Freedom National (2012), Oakes demonstrates that the Republicans were almost entirely united on nearly all wartime votes regarding emancipation and abolition. Their differences emerged on other issues, such as reconstruction, a fact that the movie obscures.

Benjamin Schmidt, a graduate student from Princeton, has an eminently teachable piece in The Atlantic on the film’s linguistic anachronisms (January 10, 2013). Schmidt was able to employ an arsenal of textual databases and easy-to-use tools such as Google’s Ngram viewer to figure out exactly which words and phrases from Tony Kushner’s script were out of place for that period. Despite Kushner’s brilliance with language, there were many problems of that nature, from important but modern phrases such as “racial equality” to gritty, non-period-style cursing.

Writing for the New York Times “Disunion” series, Philip Zelikow from the University of Virginia dismisses all such academic nitpicking and grandly dubs the filmmaker, “Steven Spielberg, Historian” (November 29, 2012). Zelikow, a diplomat whose specialty is 20th-century history, actually claims that the movie offers an “original” interpretation of the Civil War’s endgame that will “advance the way historians consider this subject.” Zelikow argues that Kushner and Spielberg have pulled together various strands concerning the slavery amendment and the Hampton Roads peace talks in a way that no previous historians have accomplished. Naturally, many historians working in the Civil War field find this claim to be seriously overstated. Michael Vorenberg, author of Final Freedom (2001), was especially pointed in his comments to Brown University students on their Facebook discussion of the movie. Vorenberg calls Zelikow’s piece “way off” and argues that “it’s unfortunate that Zelikow trashes historians in that piece” when “it’s clear that all he’s done is to skim a few pages of some books” (November 30, 2012). Other scholars quickly jumped into this fray –see especially thoughtful comments from Akim Reinhardt and Gary Gutting.

Michael Vorenberg

What’s most interesting about Vorenberg’s strong reaction is that his work was critical to the making of the movie. Some even believe it might be the most influential secondary source behind the film –at least that’s what Timothy Noah has been arguing in The New Republic (January 10, 2013). Vorenberg’s Final Freedom (2001) is widely regarded as the best academic study of the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which is the main topic of the movie. Noah points out the Steven Spielberg optioned Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals (2005) long before it was actually written and that Tony Kushner’s final script bears little resemblance in style or content to the book from which it was “officially” adapted. Both the online magazine Slate (January 10, 2013) and the Brown University student newspaper (January 13, 2013) also reported on this brewing mini-scandal until Kushner responded by acknowledging that even though Vorenberg’s book is not credited in the film, it is what he termed the “definitive account” of the congressional passage of the amendment and “fantastic” in its achievements. Kushner says that he read Final Freedom carefully but denies that it was a “principal” source for the movie. To help allay any concerns about his use of sources, Kushner then shared with Noah a list of more than thirty sources –both primary and secondary—which he claims were especially influential in shaping the script beyond Team of Rivals. Vorenberg was gracious in his response. “Films don’t have to have footnotes,” he told the Brown student newspaper, “If my book helped add accuracy to the film, I can take some pleasure in that.”

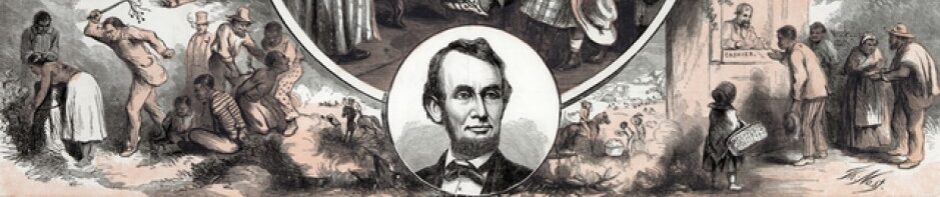

Historical author / blogger Kevin Levin finds the whole process of historical analysis to be more than a little aggravating. Writing for The Atlantic, he complains, “Historians Need To Give Steven Spielberg A Break” (November 26, 2012). I agree with Levin in some ways, but for the opposite reason. I have argued for Quora (and Huffington Post) that people must stop worrying about whether any movie which necessarily invents dialogue, characters and scenes should ever be considered as “historically accurate.” It’s a work of art –historical fiction—which we need to judge by other standards (November 27, 2012). That’s also the point, Spielberg himself made at the Dedication Day ceremonies at Gettysburg (November 19, 2012) when he called his effort a “dream” and made a careful distinction between his historically inspired movie and actual works of history. The rest of this teacher’s guide will help explain, however, specific areas in the film where students might raise questions about accuracy or interpretation, in order to help them decide for themselves what they think about the film, the challenges of the period, and ultimately, Lincoln’s legacy –both as a president and as movie.

Earlier versions of this piece have appeared at Quora and Wikipedia.

Pingback: House Divided Project of Dickinson College | Enfilading Lines

Pingback: Abe Lincoln Resurfaces, Still Helping with our Better Angels | That Devil History

Dear Colleagues

Thank you for this conspectus of links to scholarly opinion.

It is encouraging that a movie elicited it and seems to survive

it better than might have been expected, given the commercial imperatives of the film industry.

Best regards

David Broadhurst

http://physics.open.ac.uk/~dbroadhu/