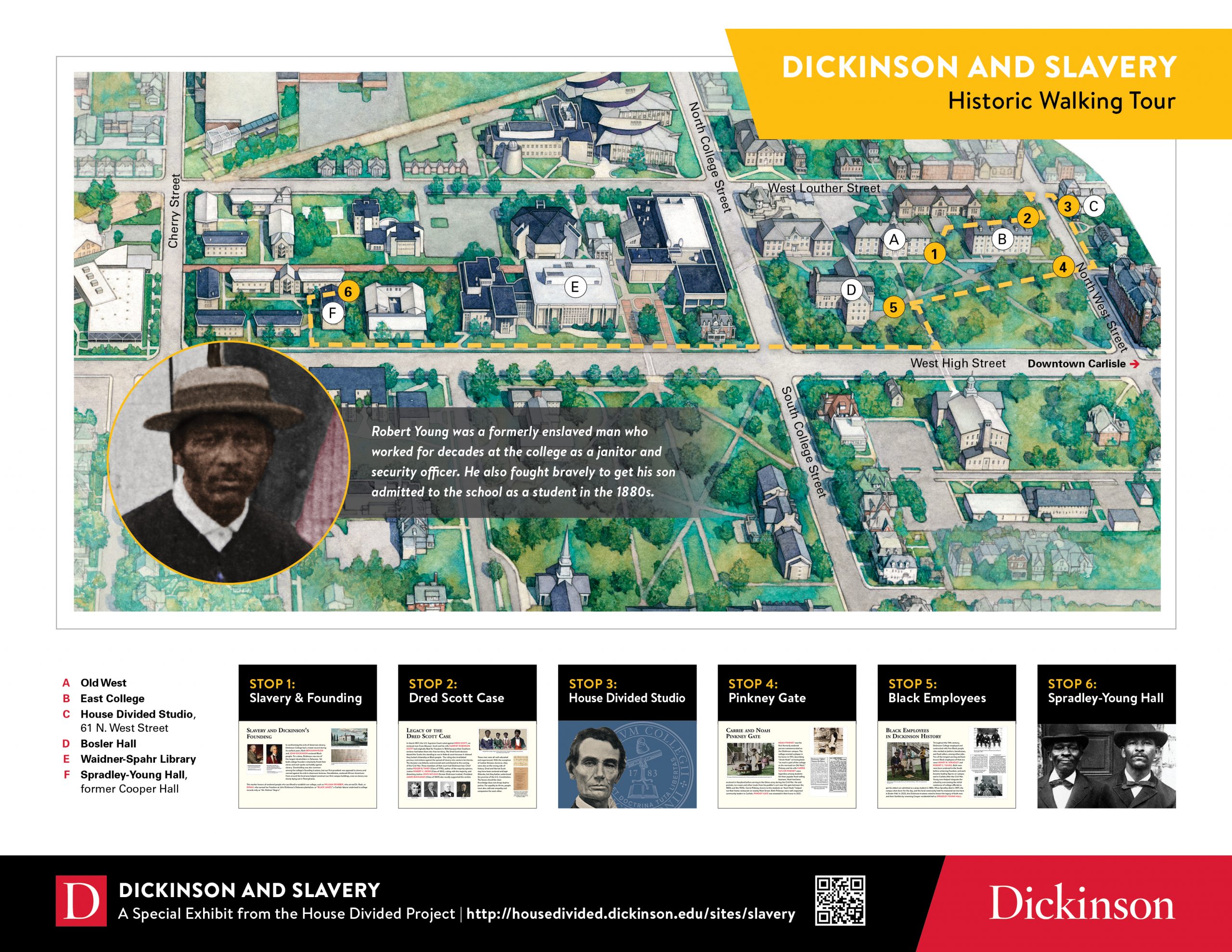

Historic Walking Tour

*** Download Historic Walking Tour brochure here***

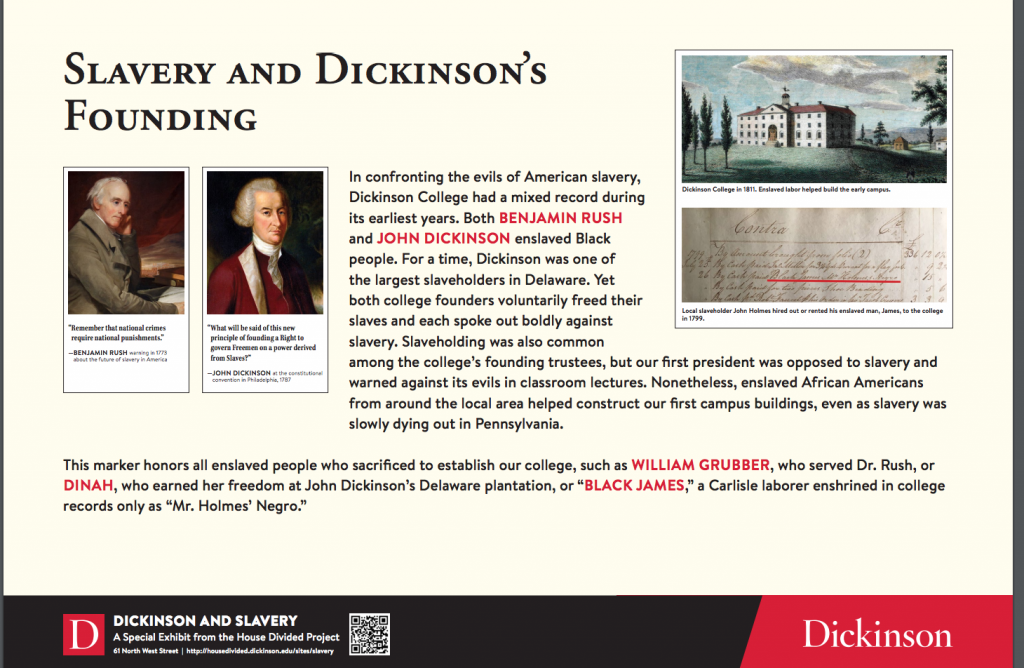

STOP 1: SLAVERY AND DICKINSON’S FOUNDING

Location: Outside Old West, facing Benjamin Rush statue

Slaveholders were closely involved in the construction of the first college buildings, between 1798-1805, supplying both materials and enslaved labor. While Dickinson College did not own any enslaved people, local slaveholders hired out their slaves to the college. We know for certain that Carlisle slaveholder John Holmes hired out his slave “Black” James to the college in 1799. When Holmes journeyed to Baltimore on behalf of Dickinson that year, James accompanied him. Upon their return, Holmes billed Dickinson for 16 days of James’s time. Later, James was hired out to work on the construction on campus. More Cumberland County slaves were likely involved in the construction. In 1799, a man referred to as “Black Ned” was also paid for work, but his status (as free or enslaved) is left unspecified in the college records. Later, in the construction of West College, John Welch, a slaveholder from neighboring Franklin County, supplied wooden posts. Similarly, Charles McClure, a slaveholding trustee from nearby Middleton township, agreed to deliver 3,000 bushels of sand. Both men surely used enslaved labor in providing their services to the college.

For more information, go to our research page on the College Founding.

Directions to next stop: Walk about 25 yards behind East College heading along the diagonal pathway toward the Louther Street gate

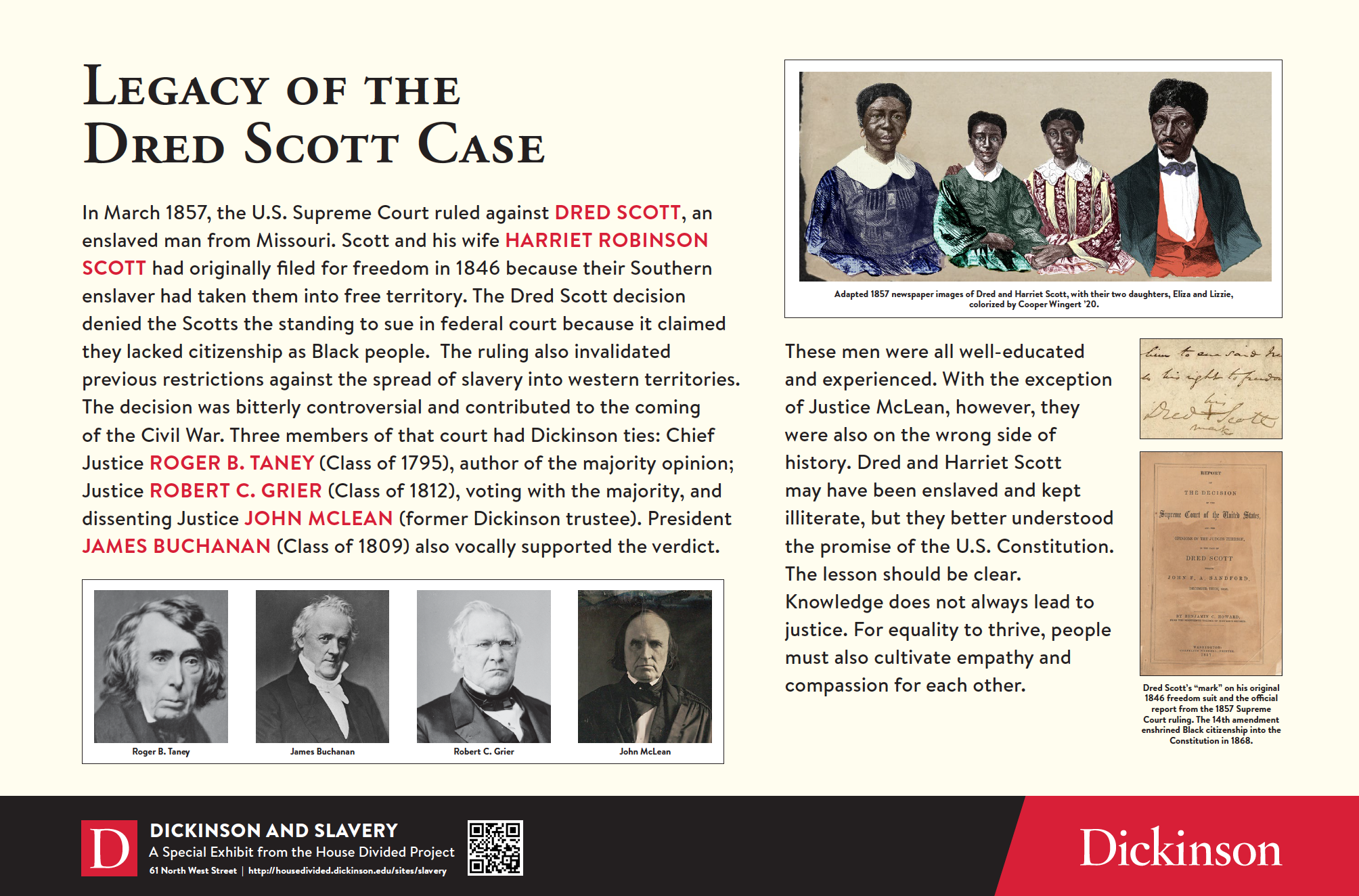

STOP 2: Dred SCOTT CASE

Location: Behind East College, facing House Divided studio

In 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott, an enslaved couple living with their two daughters in St. Louis, Missouri, filed separate freedom suits in state circuit court claiming they had been held illegally as slaves in free states and territories. They lost the first round on a technicality, but won a later round. In 1852, however, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned their freedom suit victory and threw out decades of precedent favoring the “once free, always free” doctrine of interstate comity. The state’s chief justice noted pointedly, “Times now are not as they were.” Dred Scott then took their case into federal court, and eventually the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against him in Scott v. Sandford (1857). It was Chief Justice Roger Taney who announced the court’s sweeping 7-2 opinion against Scott on March 6, 1857. Taney’s opinion for the majority ruled that blacks could not be considered U.S. citizens, that southern states did not have to honor northern laws regarding returned slaves; and that Missouri Compromise of 1820 had itself been unconstitutional because Congress lacked the authority to restrict slavery in the territories. He was joined in this verdict by fellow Dickinsonian, Robert C. Grier. Associate Justice Grier also took it upon himself during the final tense days of the court’s deliberations to keep another Dickinson alum, President-elect James Buchanan, aware of the secret discussions. When the final verdict was announced in March 1857, there were two dissenting justices. One of them, John McLean of Ohio, also had Dickinson connection. He had been a member of the college’s board of trustees for over two decades, from 1833 to 1855. Despite losing, Dred Scott and his family received their freedom in the spring of 1857. Taylor Blow, son of Scott’s first owner and a resident of St. Louis, actually purchased and then manumitted the entire family. Dred Scott died the next year, a free man. His wife and daughters, however, survived the Civil War. Some of their descendants are still alive today.

For more information, go to our research page on the Sectional Crisis.

Directions to next stop: Exit Louther Street gate and cross West Street at the intersection

STOP 3: HOUSE DIVIDED STUDIO

Location: 61 N. West Street, near the corner of Louther Street

The House Divided studio contains a variety of museum-style panels on Civil War era topics, including the main Dickinson & Slavery exhibit, which opened in January 2019. The studio is currently open by appointment only, but there are outdoor panels available for daytime viewing by anyone on topics connected to the Underground Railroad, emancipation, and the coming of the Civil War. Behind the building, visitors may also enter “Freedom Courtyard,” which contains several murals dedicated to the free black and formerly enslaved people who worked at Dickinson College during the nineteenth century.

For more information, read our Dickinson & Slavery exhibit catalog and the 2019 report

Directions to next stop: Walk up West Street toward High Street about 25 yards, then cross street toward Pinkney Gate on campus

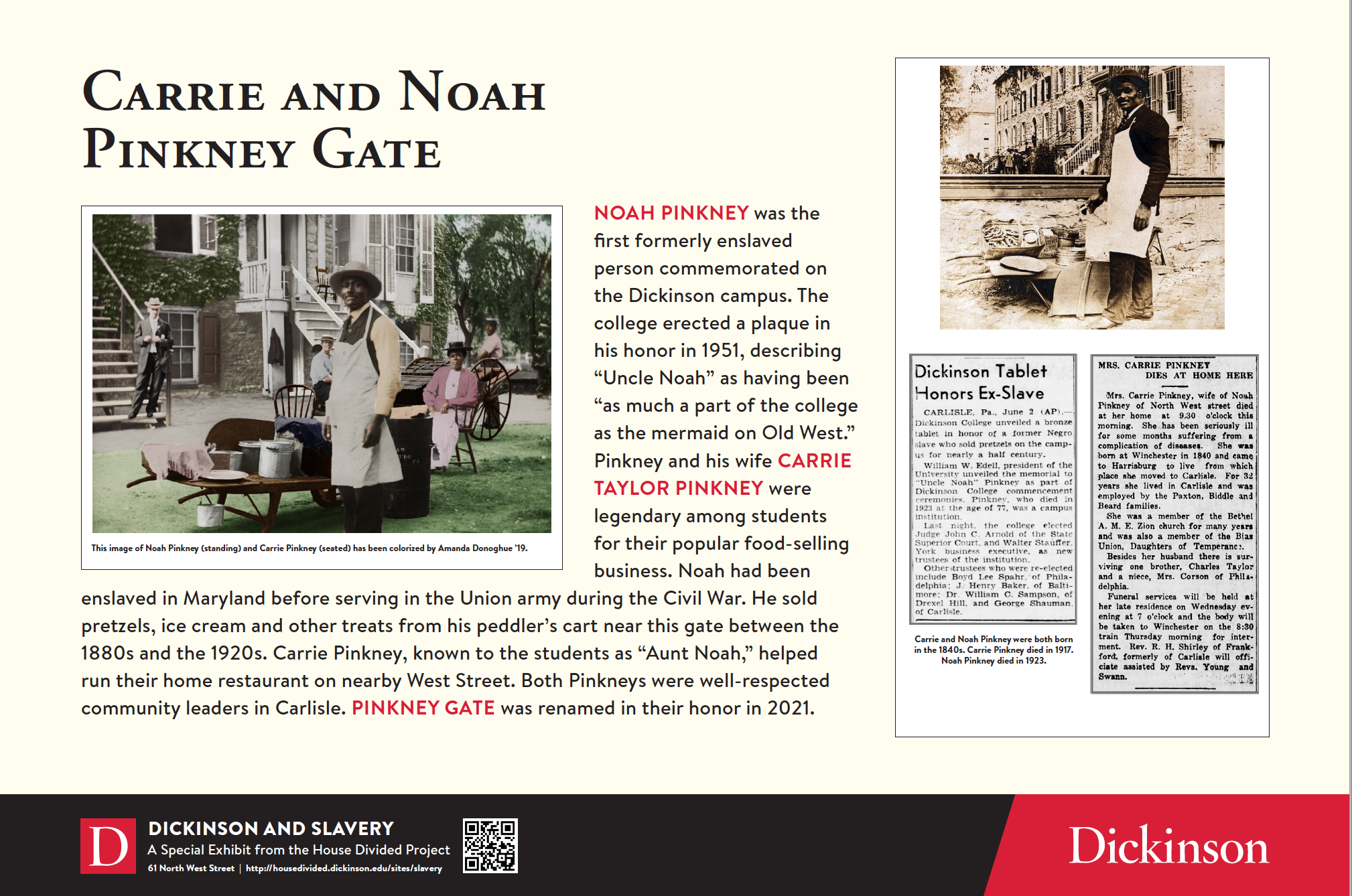

STOP 4: Pinkney gate

Location: Gate near West Street, facing East College

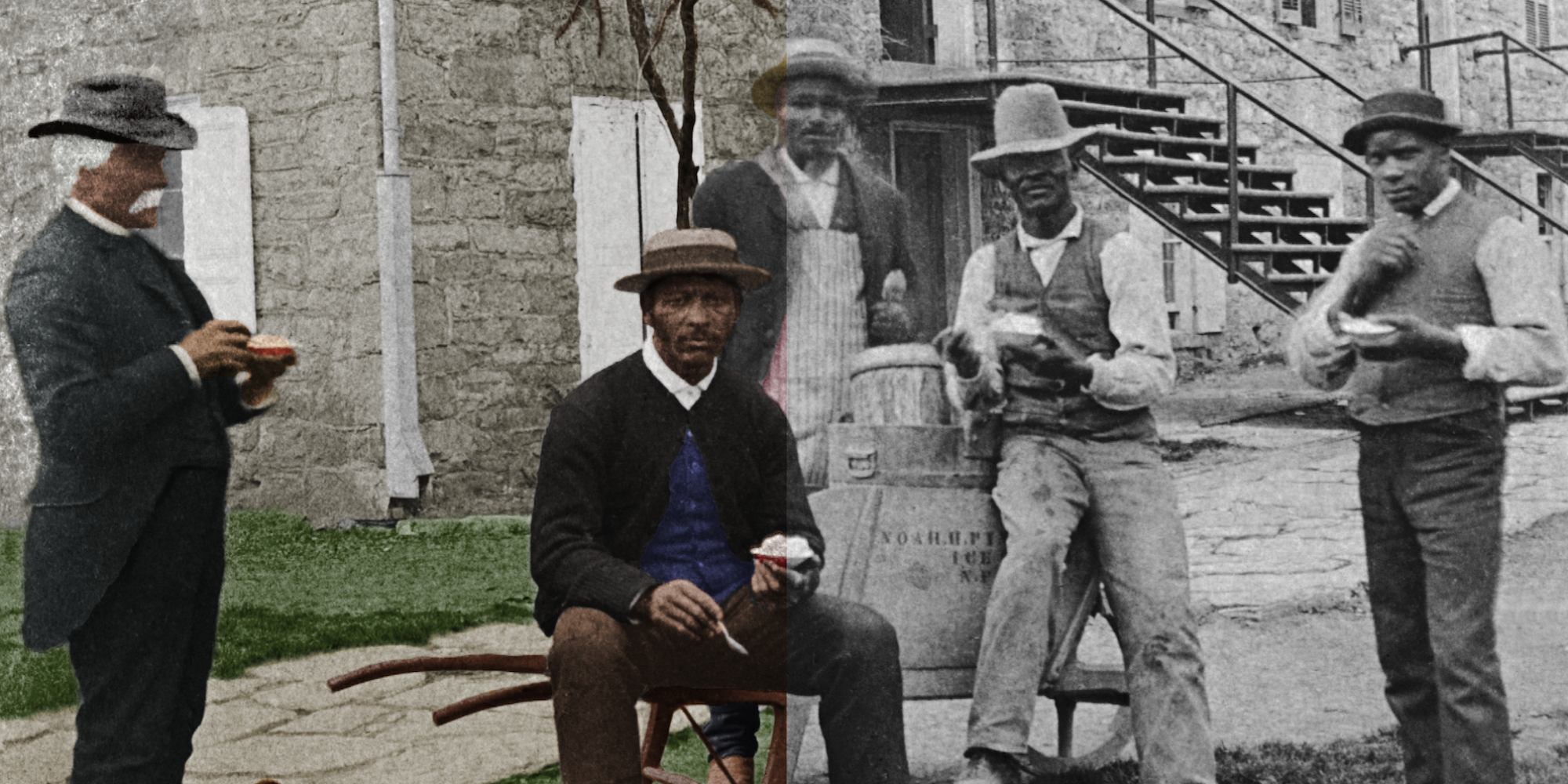

For decades around the turn of the twentieth century, a black man and his wife sold pretzels, ice cream, and other treats at Dickinson College. Noah and Carrie Pinkney were beloved figures on campus, but the students seemed almost indifferent to the couple’s true accomplishments and remarkable resilience. They sometimes teased “Uncle Noah” for his southern accent and remembered Carrie Pinkney only as, “Aunt Noah.” But Carrie Pinkney was a prominent fixture in Carlisle who was born into slavery in Virginia and yet lived until the age of 77. Noah Pinkney was a formerly enslaved man from Maryland who had fought with the Union army during the Civil War and was present with his all-black regiment at Appomattox in April 1865. After the war, the Pinkneys did not just manage a successful food-selling business in Carlisle. Noah Pinkney was also a town leader, a precinct organizer for the Republican Party, a commander of his local GAR post, and a civil rights activist. None of these facts got mentioned when Dickinson College first put up a memorial plaque in Pinkney’s honor during the early 1950s. But still, for decades, Noah Pinkney was the only formerly enslaved person recognized on the Dickinson campus. Beginning in 2020, however, the college announced plans to rename the East College gate after both Noah and Carrie Pinkney, as a way to acknowledge their remarkable struggle for freedom, and their years of service to the college and local community.

For more information, go to our research page on Noah Pinkney

Directions to next stop: Walk across the main quad about 50 yards toward Bosler Hall, near High Street

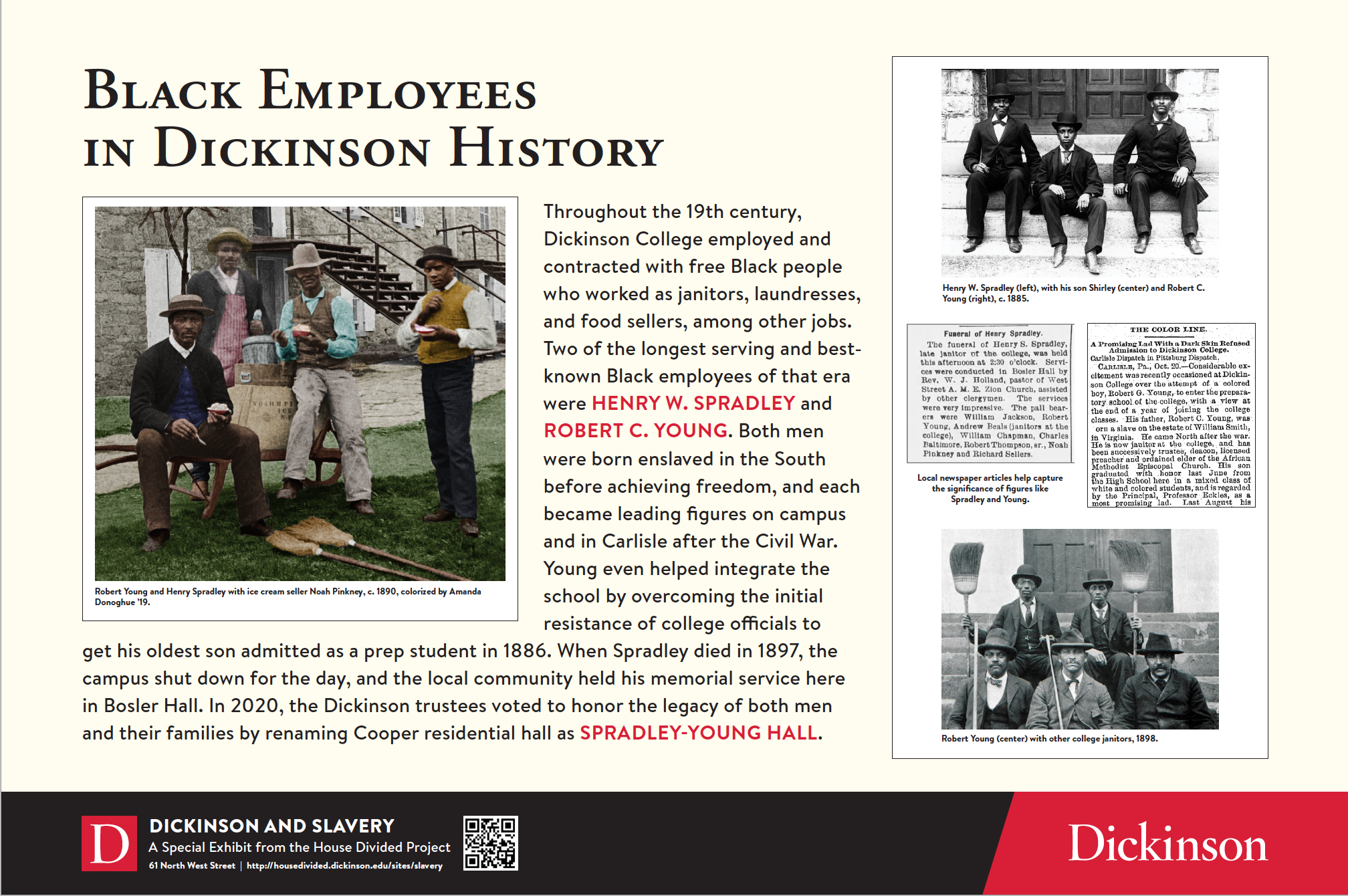

STOP 5: BLACK EMPLOYEES

Location: Near Bosler Hall, facing High Street

According to rules established by the college in 1830, janitors at Dickinson were required to ring the college bells, start and put out fires in classrooms and the chapel during winter months, attend faculty meetings to help summon wayward students, provide food services, and to employ additional labor whenever needed to help maintain the college buildings and grounds. Janitors were also considered partially responsible for protecting the security of the campus, and especially for keeping away unwanted vendors. Their job was important and critical to the success of the college. Moreover, to sustain this perpetual workload, nineteenth-century college janitors routinely lived on the Dickinson campus in the same buildings as the students. Many of their wives assisted with washing, boarding and other domestic chores for the young men. Their children played on the college grounds, and sometimes worked for hire themselves. The janitors and their families thus interacted with most Dickinson students on a near daily basis. No rule dictated that the college janitors had to be black men, but during the nineteenth century, it appears that all of them were black, and most were former slaves and Union army veterans. The resulting mixed race community showed plenty of signs of mutual affection, occasional friction, some evidence of juvenile pranks, and more than a few examples of shocking color prejudice. One might find all of those traits embodied in a handful of cartoons that appeared in student publications during the 1880s, such as the 1882 yearbook, the Microcosm, which featured a page dedicated to the head janitors at the time (Henry W. Spradley, West College and Robert C. Young, East College), along with some of their children and family members (Shirley, John, Bud, Bob, etc.) and pets (Colonel, a.k.a. “Kurnel”) in a parody page situated just opposite the main faculty listings. The yearbook editors decided to give the janitors some phony academic-sounding titles (Adjunct Professor of Experimental Physics, etc.), presumably as a way to mock the pretensions of a staff that the young men sometimes found overbearing.

For more information, go to our research page on Freedom’s Legacy

Directions to next stop: Exit the main quad, walk across College Street, up High Street about 150 yards, past Waidner-Spahr Library

STOP 6: FUTURE SPRADLEY – YOUNG HALL

Location: Current Cooper Hall near High Street

For many years, Robert Young was the longest serving employee in the history of Dickinson College and yet few people have remembered his name. Young was a formerly enslaved man from western Virginia who came to Carlisle in the 1860s. He worked initially as a servant in the college president’s house. Then Robert Young became a Dickinson janitor and bell ringer, working alongside Henry W. Spradley, another formerly enslaved man. Eventually, Young also took over the duties of campus policeman. But Robert Young’s greatest contribution to Dickinson might well have been his determination to integrate the school. In 1886, Young’s oldest son graduated from Carlisle high school and applied to take classes at the college where his father worked. The school administration stalled and resisted. Dickinson had never had any black students. Most American colleges in that era remained segregated. But Robert Young refused to back down. He took his family’s case to the newspapers and soon there was a national firestorm. The college eventually conceded. Robert Young’s son got to take his classes, though he never graduated from the college. However, the Young family was not done with Dickinson. Robert Young’s granddaughter, Charlotte, graduated from the school in 1934, became a teacher and lived until 2011. And in 2020, the Dickinson Board of Trustees announced that a residential hall which had previously been named after a former slaveholder and defender of slavery would now be renamed as Spradley-Young Hall. This decision honored both Robert Young, and his longtime co-worker, Henry Spradley, whose family had actually lived on the campus. It was a fitting move because these two formerly enslaved men and their families are the ones who deserve credit for integrating Dickinson College. And now, finally, they will be remembered together.

For more information, go to our research page on Robert Young