In spring 2023, students in History 204: Introduction to Historical Methods, engaged in a critical assessment of the Dickinson & Slavery initiative, offering both praise for its most compelling elements, but also providing thought-provoking suggestions for how to improve and expand. Here are some selections from their essays.

PART ONE –THE PRAISE

“Dickinson College’s project stands out as a pioneer”

“In a recent trend, many colleges and universities are reflecting on their schools’ association with slavery. The University of Virginia spearheaded a program called the Universities Studying Slavery (USS). This program is a consortium that currently includes over 90 institutions from across the globe, including Dickinson College, with a race or slavery program. Based upon a review of programs and websites by participating institutions, Dickinson College stands out as one of the most committed projects. Some programs or projects of institutions on the list appear superficial, seemingly to appear progressive, such as the University of Cincinnati, whose supposed “research” has been ongoing for five years with no output yet. Many institutions, such as Johns Hopkins University, have at least made some rudimentary postings noting at the bottom that they will post more eventually. There are only a handful of extensive, genuine, and thorough school slavery projects that are comparable to the Dickinson & Slavery initiative. Dickinson College’s project stands out as a pioneer, as today the initiative fits into the beginning historiography of schools thoroughly acknowledging its associations with slavery. The Dickinson & Slavery initiative is a quality project that succeeds in its effective but regrettably short-term plan of action for progressive change, because it should be an enduring process, not an event.”

“Humanizing people formerly lost to history”

“One of the most compelling aspects of the project, and one at which it excels, is humanizing people formerly lost to history. The project brings awareness to figures whose stories were unknown and emphasizes that they were not only impactful when they were alive but also because we can now recognize their influence in integrating the campus to become what it is today. A figure like Henry W. Spradley had such a profound impact on the campus that the school canceled class on the day of his funeral so students could attend, a rare event as Dickinson has canceled daily classes only twice since 1983, both due to weather-related incidents. Spradley was tragically trapped in Dickinson and Carlisle archives until Colin MacFarlane, class of 2012, revived his legacy. Other significant individuals like Norris, Young, Watts, and the Pinkney families were faded memories until resurrected by the Dickinson & Slavery initiative. The project excels in giving these individuals a voice, context, and character, making them and their contributions come alive from the old documents and letters through which they survived. The work of the Dickinson & Slavery initiative to humanize these individuals opened the door for the initiative’s prized accomplishment, a renaming ceremony. In November 2021, Henry W. Spradley, Robert C. Young, and the Pinkney family were honored as namesakes of symbolic campus locations. It was a momentous event for the school and the descendants of these individuals who attended. Multiple descendants in the ceremony video praised the Dickinson & Slavery initiative for bringing their ancestors’ stories to life, and some admitted they did not know of their ancestors’ activities. The renaming ceremony and the dedication of the House Divided Project genuinely touched them. Dickinson & Slavery brought justice to these individuals who deserved to be honored.”

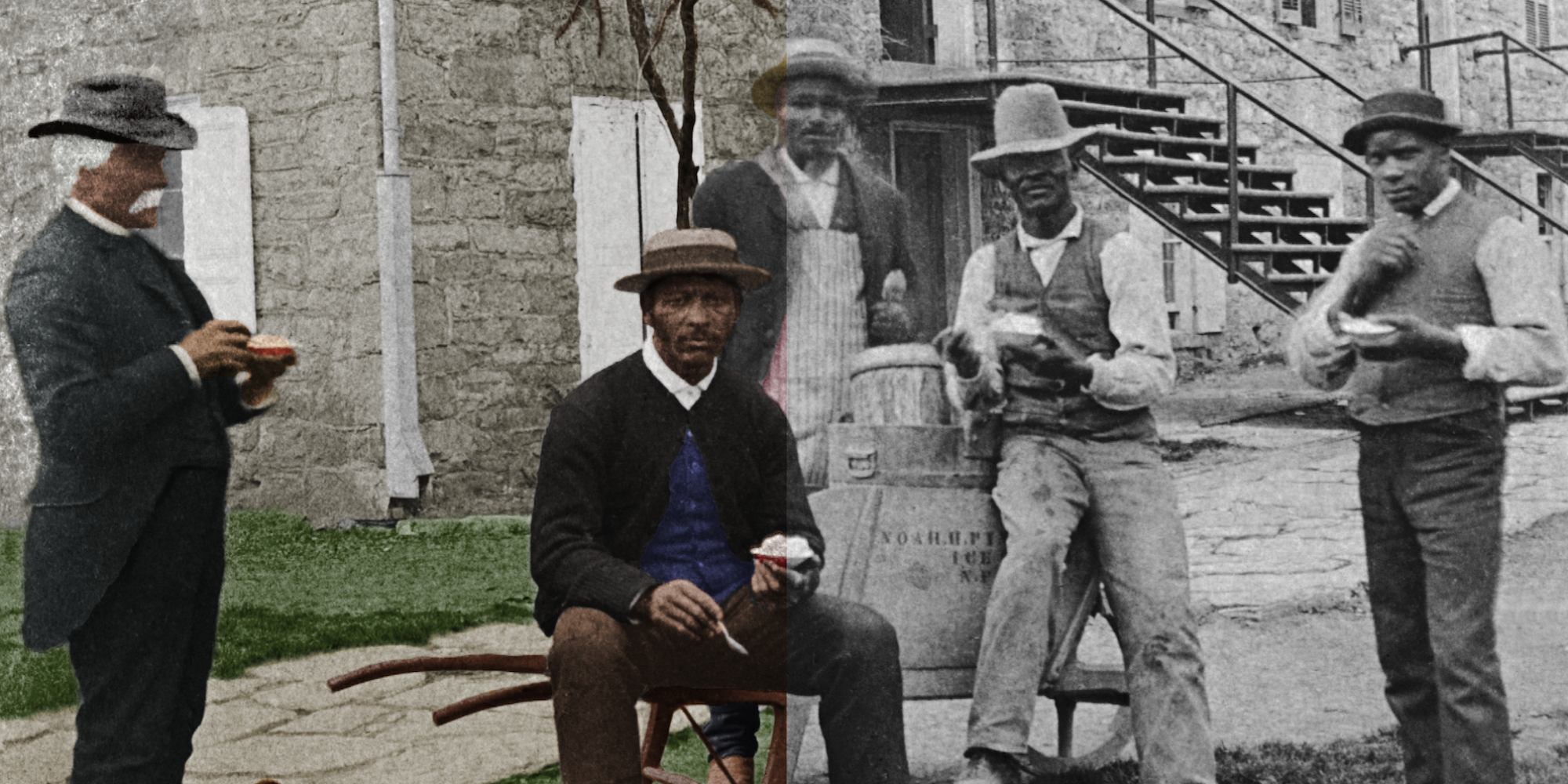

“The images are particularly powerful”

“The House Divided Studio is located next to Dickinson’s academic quad and connects its audience to the past by using a variety of techniques. From accurate facsimiles to dozens of photographs from the Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, this period of complication and conflict comes to life through Dickinson’s story. The images are particularly powerful in animating the lives of the formerly enslaved employees of Dickinson, the Watts Brothers, George Norris, Henry Spradley, Robert Young, and the Pinkney Family, key players who drive this project forward. Another step made by other universities such as Georgetown is reparations. Georgetown offered descendants of slaves admission to the university as reparations for their ancestors’ experience. Dickinson is in contact with and celebrated the descendants of the Spradley’s, Young’s, and Pinkney’s, but did not go as far as to offer them this type of reparation.”

PART TWO: THE SUGGESTIONS

“Does not fulfill its goal”

“The Report convincingly argues that renaming certain buildings on Dickinson’s campus is a necessary step toward showcasing “college values.” Yet it does not fulfill its goal to “bring to life” the stories of Spradley, Young and the Pinkneys, nor does it fully satisfy the requirements set out by its framing story. The discomfort of the anonymous Black student, whose narrative sets the tone for and gives meaning to the initiative, with the “slaveholder’s name across [her] chest” alludes to the power of names in everyday spaces: a name can be a multivalent index, which values are somewhat subjective, as well as a nexus of competing meanings. The name “Dickinson” on the shirt indexes in the first place the student’s affiliation with the school, but it also acts as a symbol for the college as a network and as an affective location. At the same time, it indicates John Dickinson’s influence and the college’s approval of his legacy—a legacy which includes enslaving others.”

“The project is not reaching or impacting the number of students that it could be reaching”

“The Dickinson & Slavery initiative is a highly organized and well-put-together project, but one clear aspect that can be viewed as inadequate is true visibility on campus. The website is easily accessible, and the report is easy to read, but the project is not reaching or impacting the number of students that it could be reaching. The renaming of certain residence halls is all some students may be able to associate with the Dickinson & Slavery initiative. One way this problem of visibility on campus could be combated is through an increase in social media promotion of the project, its exhibit, and the renaming process. Social media is extremely relevant and important in the lives of today’s college students. By establishing a larger social media presence, more students will learn about the project, what has been done so far, and what the next steps are. There already is an Instagram account associated with the House Divided Project, and it has promoted aspects of the Dickinson & Slavery initiative in the past, but one could argue that it might be beneficial to create a stand alone account for the project itself. An additional way of promoting the initiative via social media could be having “takeovers” on Dickinson College’s already existing official social media profiles. For example, these “takeovers” could give a tour of the project’s exhibit at the House Divided Studio by students. Being promoted on Dickinson College’s main social media profiles would bring more people to the exhibit at the House Divided Studio, more traffic on the website, and possibly an advancement into the next stage of the renaming process. Visibility is imperative to the success of an initiative like Dickinson & Slavery, and with an increase in social media presence, the project would have a much greater impact on the students and faculty of Dickinson College.”

“Tell these stories in a way that is both purposeful and casual”

“Students may not recognize a photograph of Henry Spradley, but they likely recognize the former students whose photographs line the hallway between the mail boxes and the Mail Room on the ground floor of the Holland Union Building. Any student who has waited for a friend at the “cushies” on the top floor of that building will recognize the photograph of Soo Min Kim ’18, who won the Miss Korea 2018 pageant. Spaces where students loiter provide an opportunity to tell these stories in a way that is both purposeful and casual and that connects the stories’ icons with students’ affective experiences of the environment so that the stories themselves are honored and recalled as often as memories of their spaces are.”

“Continue as a process and not be just an event”

“For the Dickinson & Slavery initiative to continue as a process and not be just an event, it should evaluate further ways to grow. The project lacks an extensive archive, which should be one of the next priorities. The Dickinson & Slavery website is mainly a historical analysis with a picture of the letter or document mentioned. Many quality school slavery websites are like Dickinson’s, such as the Penn & Slavery Project, and Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery. What makes the Princeton & Slavery website stand out as one of the top projects is its searchable archive on top of its historical analysis with primary source references. If the Dickinson & Slavery initiative added an archive, it would round out the entire project while providing opportunities for further research and learning.”

“A lesson can be learned from Princeton University”

“That said, it is important to recognize that the initiative of Princeton & Slavery has a section regarding “life on campus,” in which the divisions of its community’s ideologies on the issue of slavery are acknowledged for its readers to capture a sense of life within its gates. The strain that the opinions of slavery had on the Princeton student body were reminiscent of those at Dickinson, and with respect to the Dickinson & Slavery initiative, a lesson can be learned from Princeton University. As Princeton & Slavery has a focus on an examination of the conflicted opinions that caused strain to their community, the same can be done with the Dickinson & Slavery initiative as a way to further engage its readers.”

“Falls short of providing a complete narrative”

“Although “Dickinson & Slavery” brings to light the stories of some forgotten black figures at Dickinson College, it falls short of providing a complete narrative of their experience. This is not for lack of trying, but rather for a lack of physical evidence. Literacy is an overwhelmingly important factor in the preservation of history. The written word is, traditionally, the most reliable and well-preserved record of human thought and experience. However, emphasis on using the written record to establish the “truth” of history is a complicated matter, as it tends to disregard the experiences of those who were illiterate and those whose records were not preserved. While not the only illiterate group by any means, the largest group of illiterate individuals during the founding and early years of the United States was the enslaved population. Their illiteracy was not because they did not want to learn, rather it was due to the illegality of teaching enslaved individuals to read and write. Heather Andrea Williams’ book Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (2005) discusses the fight for education (specifically literacy) that black people experienced while enslaved and following their emancipation. Williams neatly summarized the attitudes about the literacy of African Americans during the Antebellum period, “Whites feared that literacy would render slaves unmanageable. Blacks wanted access to reading and writing as a way to attain the very information and power that whites strove to withhold from them.”

“Looking at the intersectionality of our history”

“In terms of content, the report and initiative at large is comprehensive in its documentation of the many African Americans who were involved with the college in its first century or so of existence, typically in the role of campus janitors. A quick look at the endnotes demonstrates that a lot of time and effort went into the research for this project, and many sources were consulted. Where the content may be lacking, however, is in its recognition of the black women who were connected to the Dickinson campus. Carrie Pinkney, who is now honored alongside her husband Noah with the Pinkney Gate, is included in the report and for good reason. But is she truly the only black woman who was involved with Dickinson prior to when the first black female graduate, Esther Popel Shaw, graduated from the college in 1919? Perhaps the role of black women on campus is less apparent than that of black men, but an effort should be made to ensure that nothing was missed. Why was the first black female graduate over a decade after the college’s racial integration, and nearly four decades after the college began to admit female students? On a diverse campus such as Dickinson, looking at the intersectionality of our history—that of both African Americans and women—remains exceedingly important.”

“Could further recognize the early contributions of enslaved people”

“Long overdue but it’s a long way” pronounced Carol Rose at the renaming ceremony for Spradley-Young Hall. She spoke as the great-granddaughter of Robert Young, for whom the old Cooper Hall was being renamed. In this statement, Rose hinted at a key goal of the Dickinson and Slavery project. By its own assertion, the project aims to “seriously reexamine the historical connections to (and complicity with) enslavement of Dickinson College.” The renaming of this building was the culmination of immense research and work but constitutes only one piece out of a much larger effort to engage with Dickinson’s legacy. Dickinson and Slavery includes several elements, which succeed especially in the realm of making learning and teaching about the topic of slavery more accessible. In looking to next steps, the project could further recognize the early contributions of enslaved people through reparations to various local efforts which address racism and slavery in the Carlisle community.”

“Few references to the broader Carlisle community”

“While the report engages the public with Dickinson College, there are few references to the broader Carlisle community which leave gaps in our understanding of who these janitors were, and why they should be memorialized as they are on campus. More emphasis on the janitors’ lives outside of Dickinson would help paint a richer picture of the era in common society, rather than the more elite circle of a college.”

“If the College were to proceed with reparations”

“However, because of an inability to identify specific descendants, if the College were to proceed with reparations, it is necessary to consider to whom these should be paid. In this instance, reparations take the form of money, time, or resources as repayment for the unjust labor used in Dickinson’s early years. There exist several organizations in Central Pennsylvania who dedicate resources to work against racism and could be the recipients of these resources. The YWCA Carlisle, Racial Justice Initiative has numerous programs committed to this work. These include the Stand Against Racism Challenge, which provides materials for three weeks of self-guided learning about anti-racism and a program for elementary age students held on Matin Luther King Jr. Day for children to learn about African American History. Another organization which has a branch in Carlisle is Not in Our Town which attempts to engage community members through a variety of taskforces (including educational, municipal, and more) a response to hate-groups distributing leaflets in the town in 2019. It is possible to donate monetarily to both of these organization.”

“The goal of reparations would be to educate”

“Furthermore, it is necessary to engage with potential objections to reparations. People might ask why those in the present day must pay for things that occurred long before they were born. Others might argue that due to the difficulty in finding the descendants of the enslaved people who worked at and for Dickinson, the college should not have to pay to an organization that might have nothing to do with slavery directly. In responding to these criticisms, though, one can offer the following reaction. Though no one alive today who works at or attends Dickinson personally owned slaves, the College still benefits from their largely uncompensated labor simply by living and working in buildings (or the remodels of buildings) that they built, with supplies they had to transport. As for the recipients of the reparations, the statistic that for every one dollar a white family in Carlisle makes, a Black family will make 54 cents is pertinent in addressing the legacy of slavery. Indeed, the Carlisle Black community feels the legacy of a system that placed them at an economic disadvantage to their white neighbors. The goal of reparations would be to educate on and reduce this ongoing disparity, while keeping in mind the history that created this inequality.”

“Launch into the second phrase of renaming”

“One object that particularly stands out in an otherwise scattered table of documents, is a letter from Dean George Allen in April 1991 regarding the renaming of the Fraternity Quadrangle residence halls. The quad buildings’ names had negative ties to slavery and there were concerns of the names lack of diversity. Cooper’s pro-slavery attitudes, Armstrong’s prolific native American treatment, and the overall repetition of old, white men seemed to overshadow the histories of other demographics that played a large role in Dickinson’s history. He lists the accolades of these men and why they should be left as namesakes. The Dean saw “no point in naming a building after the first black or the first native American who attended Dickinson, nor the first woman professor.” This document is what would launch the project into the second phase of renaming as well as chronicling the positions of inclusivity over time, beyond the period of the Civil War. Exploring the nuance of this decision could further illuminate the complications of humanity regarding representation. Norms and values shift over time, and this is an important contribution to Dickinson’s narrative. By exploring more issues surrounding inclusivity on campus, the greater insight we have into the human condition. The report is right in identifying renaming as something to approach on a “case-by-case basis.” The next phase, in opposition of Dean Allan’s sentiments, should include notable men and women of color and outshine the men identified who were “slaveholders or pro-slavery figures who never renounced slaveholding”: John Armstrong and John Montgomery. There is a difference between changing and preserving history. The notorious memories of John Armstrong and John Montgomery should live on the floor of the House Divided Studio and leave space for new Dickinsonian voices to be heard.”

“Rename Armstrong Hall”

“A future move that the Dickinson and Slavery Project could make is to continue to push to rename Armstrong Hall and replace his controversial namesake with someone who is less controversial and embodies the better aspects of Dickinson. One idea would be to rename it to one of Dickinson’s first Native American graduates, Frank Mount Pleasant, who was also a decorated athlete for the college and respected student. Born in 1884 on the Tuscarora Reservation in Western New York, Mount Pleasant attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School from 1902 to 1908 and became one of their most storied students. He played alongside Jim Thorpe, another football icon under the coaching of “Pop” Warner, playing a critical role on one of college football’s earliest dynasties. Mount Pleasant also placed 6th at the 1908 London Olympics in the long jump event, doing this prior to his time at Dickinson College. He was a star athlete for the college, including being a team captain and a top player for the Dickinson football team, setting school records on the track team, and making the Athletic Hall of Fame in 2005. Mount Pleasant’s impact on the college is especially notable, especially considering that he was one of the first Native Americans to graduate from Dickinson College in 1910, and how he graduated from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, showing that Mount Pleasant is a critical piece within Carlisle history.”