PUBLIC MEMORY AT DICKINSON

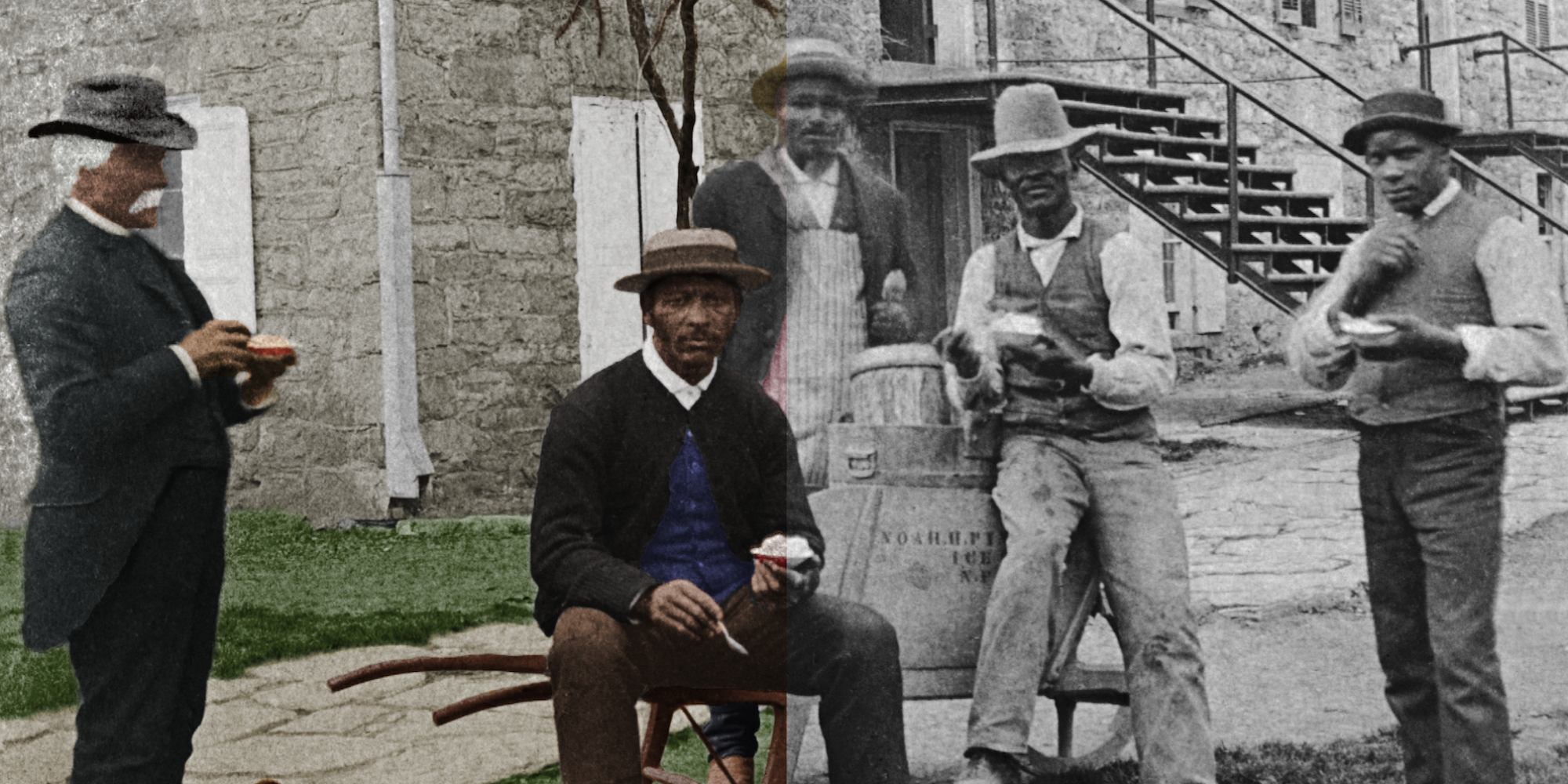

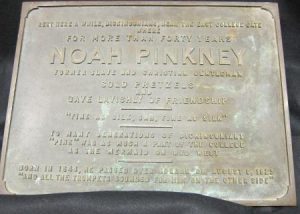

In June 1951, there was a bronze plaque near East College erected in honor of Noah Pinkney, “a former slave and Christian gentleman” who had served the college community for more than forty years. That memorial –the first ever dedicated on campus to a formerly enslaved figure –was apparently stolen in 1978, but eventually recovered and moved over to the College Archives. In 2013, the college rededicated a new plaque (with some updated wording) to help honor Pinkney’s legacy. That 2013 effort built on some important senior thesis work about him and other Blacks at Dickinson from Corinthia Jacobs (Class of 2011), an Africana Studies major. In 2021, Dickinson officially renamed East College Gate as Pinkney Gate, in honor of both Noah Pinkney and his second wife, Carrie Taylor Pinkney. The popular couple had worked together for decades providing food services to students and the local Carlisle community while also engaging in a variety of civic and church-related activities.

In June 1951, there was a bronze plaque near East College erected in honor of Noah Pinkney, “a former slave and Christian gentleman” who had served the college community for more than forty years. That memorial –the first ever dedicated on campus to a formerly enslaved figure –was apparently stolen in 1978, but eventually recovered and moved over to the College Archives. In 2013, the college rededicated a new plaque (with some updated wording) to help honor Pinkney’s legacy. That 2013 effort built on some important senior thesis work about him and other Blacks at Dickinson from Corinthia Jacobs (Class of 2011), an Africana Studies major. In 2021, Dickinson officially renamed East College Gate as Pinkney Gate, in honor of both Noah Pinkney and his second wife, Carrie Taylor Pinkney. The popular couple had worked together for decades providing food services to students and the local Carlisle community while also engaging in a variety of civic and church-related activities.

BRIEF PROFILE

From College Archives: “Though never an employee of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Noah Pinkney was one of its most famous names for forty years. Known to Dickinson students as “Pink” or “Uncle Noah” for all of that time, Pinckney was born a slave in Frederick County, Maryland on December 31, 1846. During the war he became “contraband” and in 1863, he travelled to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to enlist in the Union Army. He served under General Butler and, according to the Dickinsonian, was present at the Appomattox Court House in April 1865 when General Lee surrendered. Following the war he made his home in Harrisburg where he lived until he moved to Carlisle in 1884. From the next twenty years, “Pink” sold pretzels, sandwiches, ice cream, cakes, and pies from under the steps of East College and also made nightly rounds of the undergraduate rooms. On the coldest of winter days he would sell his treats from his three room house on West Street. Students would listen for his common line of “Fine as silk, sah. Dickinson sandwitches, fine as silk.” In 1894, he was forbidden to sell his treats on campus, and after a time serving students from outside of the East College gate, he suspended his operations for a few months. By the next spring, though, his catering had once again recommenced from his home on 137 North West Street. The May 1895 issue of the Dickinsonian celebrated the fact that “Once more is heard, the old, familiar cry, ‘Let’s go to Pinkney’s'”. After suffering for several months after a slight stroke, Noah Pinkney died at his West Street home on August 6, 1923 at the age of 77.”

Complicated family history: Pinkney’s father Enos (or Ennis) and his mother Mary were from Frederick, MD. Pinkney was born enslaved in Frederick but somehow escaped to Harrisburg during the Civil War and was living there with his extended family by 1870. Pinkney had three wives. His first wife, Margaret, probably separated from him in the 1870s but the couple did not get legally divorced until 1881. According to the 1880 census and Harrisburg directory, she was living with their daughters Sarah and Ellen Elizabeth (a.k.a. Ella), while he stayed with his mother Mary, also then residing in the city. Noah Pinkney’s second wife Carrie Taylor Pinkney (originally from Winchester, Virginia) claimed to have married Noah in 1875, but they may have been living together as a common law couple, at first in Harrisburg and then probably in Carlisle after 1884. We have not yet found any official marriage records for Noah and Carrie Pinkney. She died in 1917. Carrie Pinkney, known as “Aunt Noah,” by Dickinsonians, was the woman whom everyone on campus remembered as Pinkney’s wife and food-selling partner. The couple apparently had no children, but they did live with their niece Gertrude Taylor, age 16, in 1900. Two years after Carrie’s death, Noah remarried for a final time, to Nan or Nannie Folks. She was a younger woman, about 40 years old at the time of their marriage, born in Pennsylvania.

Noah Pinkney’s daughter from his first marriage, Ellen or Ella, married a laborer in Harrisburg named Charles Brumback around 1890. They separated or divorced soon, however, or perhaps he died, because she was listed in subsequent city directories as a “widower” (a term used for either divorcees or actual widowers in those years). However, Pinkney and his daughter maintained some kind of relationship, because “Mrs. E. Brumback” was listed as the official witness to Noah’s life history on his 1923 death certificate. (Special thanks to Sam Lavine (’22) for helping to identify this information about the Pinkney family.)

FURTHER READING

- Dickinson Archives: Noah Pinkney (1846-1923)

- House Divided research engine: Pinkney, Noah

IMAGE GALLERY

PRIMARY SOURCES

- 1900 || Boyd L. Spahr, Dickinson Doings: Ten Stories (1900)